Let’s start with Australia. To observe the goings-on in the five-star hotel that hosts the Shangri-La Dialogue was to see quite clearly that we are no longer in Beijing’s naughty corner – or at least not more so than almost every other wealthy liberal democracy struggling to deal with Xi Jinping’s assertive rising power.

Canada and to a lesser extent Japan and South Korea are the US allies in the region getting the worst of it from the Chinese.

“You were at one extreme. Then you went to the other extreme,” one of Singapore’s greatest foreign policy brains told me in Shangri-La’s wood-panelled Origin Bar on Saturday night.

His main takeaway from the Prime Minister’s keynote address was that – after a period of stunning naivety, followed by an at times hysterical correction – Australia’s China policy is sounding much more assured.

Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong personally invited Albanese to make the keynote address.

Albanese put the finishing touches on his speech, which had already gone through a few drafts, a few weeks ago on his flight to Hiroshima for the G7 and Quad leaders’ meetings. He told more than a few people during that busy trip to Japan that he was pretty chuffed with it.

Early reviews over the weekend were not all favourable.

“Boring,” a British delegate told me. “A missed opportunity,” said an Australian delegate. “Why on earth did he say ‘guardrails’? The Chinese hate that phrase,” an American delegate said.

I marked it more kindly. Albanese asserted the agency of countries other than China and the US. He was sensitive to the varied sensibilities of Southeast Asia. He wasn’t cartoonish on China. And he struck an optimistic – albeit realistic – tone on the future of our region, which too often is spoken of apocalyptically by armchair generals.

“The fate of our region is not preordained. It never was. It never is. What we do here, what we decide here, matters – for us and the world,” Albanese said. “I can assure you that when Australia looks north, we don’t see a void for others to impose their will.”

But it is true, this wasn’t a newsy address. Rather, it was a distillation of an Australian system that looks more confident and less rattled after going through a huge transformation since Malcolm Turnbull, in 2017, became the second Australian prime minister to address the Shangri-La forum.

That elegant Turnbull speech – in which he defended the rights of “the big fish, the little fish and the shrimps” of the region – did not go down well with China.

“Beijing wasn’t positive. We were being pressured to say less about the South China Sea and the geopolitics of the region,” Turnbull wrote in his memoir.

A lot has changed in the following six years. It is now routine for Australian prime ministers – first Turnbull, then Scott Morrison and now Albanese – to speak out about China’s illegal territorial claims in the South China Sea. Beijing still doesn’t like it, but it seems to understand Canberra has made up its mind. Mercifully, the days of Sam Dastyari parroting Beijing’s fatuous claims while standing next to a billionaire Chinese donor are long gone.

Afternoon tea on Saturday with a member of the Chinese delegation underlined the point.

The retired PLA officer had almost nothing to say about our Prime Minister’s speech. He had heard similar from Canberra for years now. Nothing much stood out, he said – perhaps not the worst Chinese reaction for an Australian leader.

“It seems to me that he tries to touch on a bit of everything. Therefore, you can say it is balanced,” he said, over Darjeeling tea.

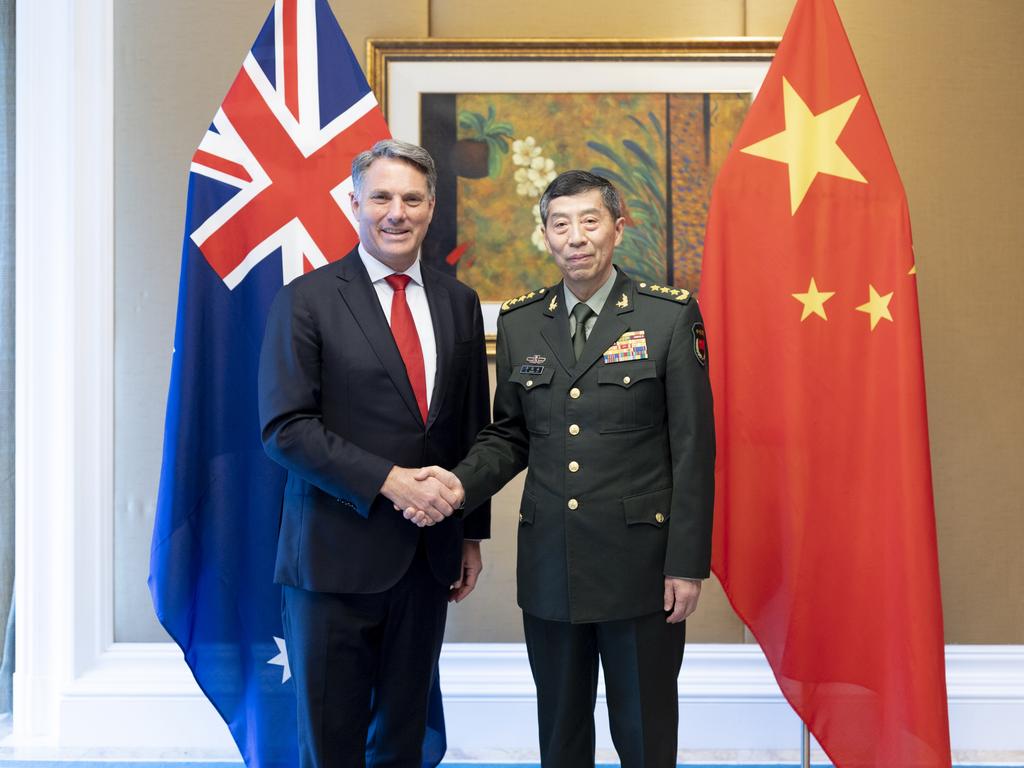

Chinese Defence Minister General Li Shangfu’s minders wouldn’t let him answer on Saturday when I asked what he had made of it. But his smiles and handshakes before and after his meeting with his Australian counterpart, Richard Marles, Defence Department secretary Greg Moriarty and Chief of the Defence Force General Angus Campbell suggested it hadn’t upset the recently “stabilised” relationship.

A senior member of the Australian government later told me the passage praising China’s economic development had gone down well, according to early feedback.

The Chinese Communist Party English language newspaper Global Times even gave it an almost positive, albeit glancing, reference in an editorial otherwise thundering about American wickedness.

Of course, the Australia-China relationship is just a small part of our multipolar neighbourhood.

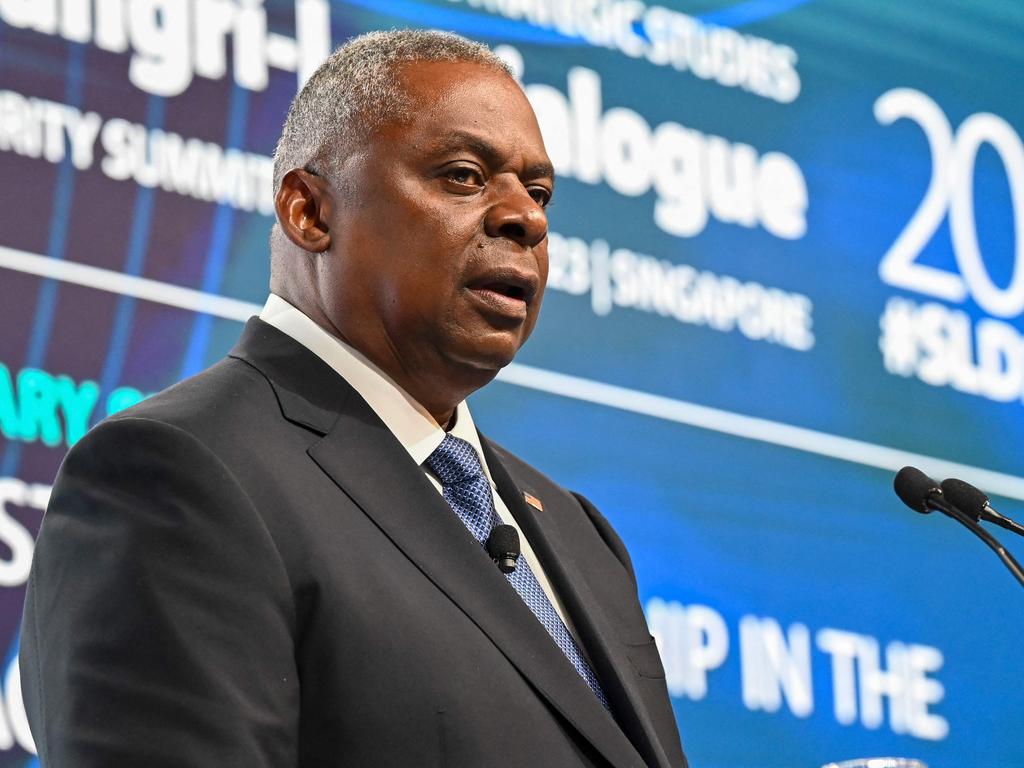

The weekend’s keynote speeches by Li and US Secretary of Defence Lloyd Austin each offered plenty of reasons for residents of the Indo-Pacific to sleep uneasily.

China appears to be incapable of accepting that countries in the region – including Australia, Japan, Vietnam, The Philippines and many more – are genuine when they express concern over Beijing’s actions. In China’s eyes, we’re all willing agents of the Americans or too stupid to realise we’ve been duped by Washington puppeteers.

Beijing’s propaganda machine tried to manufacture its own reality, claiming there was a rapturous response after Li explained Xi’s vision for a new international security order.

“After the end of the speech, the applause burst from the crowd, which was different from the polite applause after other speeches,” Global Times reported.

That was news to people actually in the Shangri-La’s ballroom.

The US, for its part, was not able to remove a Trump-era sanction imposed on Li that Beijing said made any meeting with Austin impossible. That’s not an ideal situation in the view of some senior figures in the Australian government, who noted the Chinese Defence Minister had met almost everyone else – except Beijing’s current bete noir, the Canadians.

But let’s not be too harsh on the Biden administration. Its co-ordination of Indo-Pacific allies and partners has been formidable in the 12 months since last year’s Shangri-La Dialogue. Even Chinese delegates had some kind words to say about the US top delegate.

My afternoon tea companion on Saturday, a retired PLA officer, told me one line in Austin’s speech that morning had been particularly well received: the US Defence Secretary’s assessment that “conflict is neither imminent nor inevitable”.

Austin’s authoritative rejection of alarmist predictions that have come out of the American military in recent months, including General Mike Minihan’s notorious “gut memo”, was welcomed. “The only sentence I’m interested in is that he said conflict is not imminent. And that it is not inevitable,” my Chinese companion said.

Increased recognition of exactly how much of a catastrophe for the whole world a Chinese war over Taiwan would be was a notable feature of the long weekend.

That alarm, heightened by Russia’s ugly war of annexation in Ukraine, is why the Chinese Defence Minister’s threats of war on Sunday completely overshadowed his earlier attempts to cast China as an agent of peace. His belligerence was likely said as much for his nationalistic audience back home as it was Washington and Taipei, but it was still deeply unsettling. After all, some of those hyper nationalists are his political superiors, including President Xi himself.

Back in Taiwan, a senior figure in President Tsai Ing-wen’s government this week told me Taipei shared Austin’s assessment that China was not eager for war.

“It is the same assessment here in Taiwan,” he told Inquirer.

Beijing’s bluster is part of its decades-long project to deny the Taiwanese any say in their future.

Washington’s response, shared with its allies across the region, is to make sure Beijing appreciates, as Albanese said in his speech, that “the risk of conflict will always far outweigh any potential reward”.

Or as Austin put it more bluntly the next day: “Deterrence is strong today – and it’s our job to keep it that way.”

President Xi won’t like that message from Shangri-La – but it is in all of our interests that he receives it with crystal clarity.

What did I learn from my long weekend at Singapore’s opulent Shangri-La Hotel last weekend, having afternoon tea with Chinese People’s Liberation Army officers, bumping into Five Eyes spy bosses in plush corridors, having drinks with Southeast Asian diplomatic giants – and, of course, listening diligently to the speeches given at our region’s most important security conference, including the opening address by Anthony Albanese?