Tasmania suffers from too much of a good thing

It’s one thing becoming a hip new lure for art lovers, foodies and big city escapees. But that comes with several social headaches.

Tasmania and its increasingly hip capital are booming; a lure for tourists, art lovers, foodies, investors and developers, as well as mainland big-city escapees seeking a less harried lifestyle.

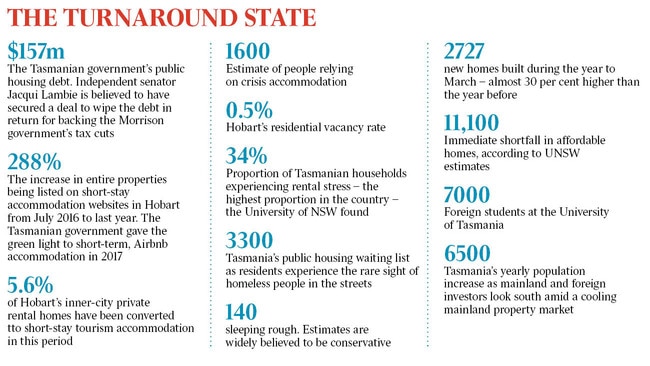

The success of what Scott Morrison dubs “the turnaround state”, however, has come with less gratifying side effects.

Eavesdrop on locals conversing in any of the increasing number of cafes and bars popping up in Hobart, and you will soon hear all about it.

About how bad the city’s traffic has become. How parking is a nightmare. And those pesky tourists overrunning once-loved favourite holiday spots.

For some, though, the downside of the state’s economic volte-face is more serious, undermining their ability to put a roof over their heads.

The island state is struggling with what many term a “housing crisis”, leaving hundreds homeless and many more couch surfing or imposing on relatives, amid a shortage of affordable digs.

National problem

Tasmania’s problem has now become the nation’s problem, after independent senator Jacqui Lambie this month secured a promise of federal help — apparently including wiping the state’s $157 million commonwealth public housing debt — in return for backing the Coalition’s tax cuts.

So what is driving the problem — and what are the solutions?

Those at the frontline of the problem trace its origins with remarkable precision: to late 2017, in the wake of the state government’s decision to embrace the “sharing economy” to help source accommodation for the burgeoning tourist ranks.

“There was quite a dramatic change in around October or November 2017, a few months after the government basically gave the green light to short-term, Airbnb accommodation,” says John Stubley, chief executive of the Hobart City Mission. “Our housing support workers found at the time the availability of rental properties just dried up almost overnight. They went from having to work hard to find (private rental) accommodation for people to just not finding any at all.”

Middle-class hit

A recent University of Tasmania report noted a 288 per cent increase in entire properties being listed on short-stay accommodation websites in Hobart from July 2016 to last year.

It estimated 5.6 per cent of Hobart’s inner-city private rental homes converted to short-stay tourism accommodation in this period. In an already difficult market, this had “a significant impact on rental supply and housing affordability”.

Many middle-class renters have been forced to lower expectations, paying more for less, forcing out some at the lower end of the market entirely. Hobart’s residential vacancy rate is just 0.5 per cent.

With such demand, rents statewide rose 13 per cent last year and continue to rise at 5.4 per cent a year in Hobart, higher than any other capital. A recent University of NSW analysis found Tasmania had the highest proportion of households experiencing rental stress: 34 per cent.

Unable to rent, hundreds have joined the public housing waiting list, which has swollen to more than 3300. Visible homelessness — something rarely seen in the past — has become more common.

Property soaring

Meanwhile, property prices took off and have yet to come in to land, fuelled by the economic boom and a population increase of 6500 people a year, as well as mainland and foreign investors looking south amid a cooling mainland market.

The median home value in Hobart has more than doubled since 2003 to $457,523, with residential property prices rising 8.7 per cent last year. The Australian Bureau of Statistics suggests Hobart prices continue to grow at 4.6 per cent a year — the fastest of all capitals, followed by Adelaide, with 0.8 per cent.

Private home construction was subdued until 2017. Constrained by skills shortages, red tape and lack of readily available suitable land, it could not respond quickly enough to the sudden upturn in demand.

It is now growing rapidly — 2727 new homes built during the year to March, almost 30 per cent higher than the previous year.

However, while this rate may keep pace with population growth, it will take years to dent the demand backlog. University of NSW estimates Tasmania has an immediate shortfall of 11,100 affordable homes.

Finding answers

So what are the solutions? Lambie claims wiping the state’s $157m debt, owed to Canberra for past public housing construction, would be transformative. “It would free up enough money to find a home for 3000 people on the critical list through accommodation and casework,” the senator told supporters in an email.

However, the welfare sector and the state government have rejected her assessment. State Housing Minister Roger Jaensch estimates not having to make the $15m annual debt repayments would fund construction of an additional 50 public housing units each year.

That is significant but hardly approaching the scale of the problem, while many fear a focus solely on “ditching the debt” detracts from the need for a larger, more holistic solution.

The state has announced an extra $5m to tackle the immediate homelessness issue; expanding existing shelters with prefabricated buildings and finding vacant hotel and motel rooms and tourist cabins.

Scale of crisis unknown

No one knows the true scale of the problem, but there are estimates of at least 1600 relying on crisis accommodation and 140 sleeping rough.

The welfare sector argues a significant cash injection into social housing is required, but steps must also be taken to expand private housing construction.

“It’s not government housing that’s going to address the housing shortfall; it’s going to be the commercial industry meeting demand that is going to be a fair bit of the solution,” Hobart City Mission’s Stubley says. He urges against viewing the problem as afflicting only the poor, saying middle-class families increasingly are affected and do not yet show up in the data.

“People tell you about having their daughter, her husband and their newborn baby staying with them in a two-bedroom unit,” he says.

“We are seeing middle-class families earning a wage who are essentially living in family members’ spare rooms because they are unable to find accommodation to rent.”

High-rise solution

Stubley argues local councils and the community need to be more willing to embrace higher-density housing, such as apartments, and new hotel developments that might ease the need for Airbnb.

It’s a controversial view uniting some strange bedfellows, from sections of the welfare sector to property developers.

However, it’s one that runs counter to a prevailing philosophy in Hobart that high-rise should be resisted, to preserve the city’s trademark views of mountain and river and its small-scale ambience.

Recent hotel developments have been opposed as too high or too ugly, as have several recent residential offerings.

A higher-density subdivision at Mary Knoll in Blackmans Bay, south of Hobart, is copping flak from locals, while a high-rise apartment block proposed for the city’s Welcome Stranger pub site was blocked this week by the city council.

“The government probably needs to take responsibility for building more affordable housing, but 90 per cent of the solution to this is just going to come from the availability of housing generally,” Stubley says. “That means land being made more available and encouraging developers, rather than discouraging them at every turn.

“Part of the problem is our philosophy of not wanting infill development and not seeing multistorey accommodation buildings as acceptable, as they are in bigger cities. What we want for our city is probably contrary to what our city needs to deal with the population growth.”

Foreign students

Stubley and others believe the University of Tasmania’s up to 7000 international students are adding to the problem.

“We haven’t really got to the bottom of how quickly UTAS is growing and how many beds they are taking out of the market by buying up hotels (for student accommodation), or how many international students are renting on the open market, adding to demand,” he says.

The Master Builders Association also says regulatory and cultural change to embrace higher-density housing is vital.

“In pretty much every other capital city in Australia — Sydney, Canberra, Melbourne, Brisbane — the composition of new housing is about 50 per cent detached housing and 50 per cent higher density,” MBA Tasmania executive director Matthew Pollock says.

“Hobart has 85 per cent detached housing and 15 per cent apartments.

“That’s not to say we should be building skyscrapers in the middle of the city. But there are huge opportunities for infill development and sensible medium-density housing. That is the most critical thing in terms of providing affordable housing options close to where people work and close to amenities and schools … Not everyone wants three-bedroom houses with a quarter-acre block.”

Pollock expects the industry will take “a few more years” to catch up with demand. He calls for fast-tracking of “sensible” developments, release of more shovel-ready land and better co-ordination of land release and the provision of essential services, such as water and sewerage and power.

Lambie goes quiet

No one is quite sure what the Morrison government has promised Lambie or may do to assist the state; it refuses to say. The singular senator also is declining to elaborate. It appears they may have agreed merely to agree to something, down the track.

Discussions between the state and federal governments — which began before Lambie elevated the issue — are ongoing, with talk of an announcement within six to eight weeks.

Any decision to wipe the state’s historic public housing debt will meet resistance from some within the Coalition.

Tasmanian Liberal senator and powerbroker Eric Abetz has been labelled a turncoat for opposing the idea. He argues wiping debt is “lazy politics” and will lead to complaints or demands from other states, which combined owe the commonwealth $2.2 billion for public housing loans.

“To ask for something for Tasmania specifically, you’ve got to make out a specific case as to where the special need is,” Abetz argues. “If you say ‘forgive the housing debt for Tasmania’, the first question is: ‘Why?’ and ‘Why not for all the other states?’.”

Housing Minister Jaensch begs to differ. “We want that debt waived,” he says, promising the state would invest the entire $15m annual windfall back into affordable housing.

The state Labor opposition claims the Hodgman government carries much of the blame for the crisis by failing to match its growth targets with infrastructure and service investment.

Jaensch insists the state’s eight-year, $200m affordable housing strategy is addressing all aspects of the problem. “There’s not one solution to the shortage of housing in Tasmania,” he argues.

“Some people need to be in social housing. Some just need help to find a block of land that’s affordable … Some need supported accommodation. Some people need assistance to compete in the private rental market. Our affordable housing action plan has dealt with people across this spectrum.

“We are also rezoning surplus government land, which will play a major role in meeting the increased demand … Under new legislation, developed specifically in response to the current housing shortage, the accelerated rezoning process shaves at least six months off the typical rezoning process.”

Even so, he concedes “there is more to do”. How much more will depend on the longevity of the state’s stellar growth — and how much Lambie and Jaensch can leverage from Canberra.

-

Catch-22 crisis for a father just trying to house his kids

Tasmania’s housing shortage is not just forcing Hobart man Craig to couch surf and camp in the scrub, it’s breaking his heart; preventing him from living with his two daughters.

The 47-year-old is caught in terrible bind — he needs appropriate public housing to regain custody of his daughters, who are in care, but he is denied such housing because he is regarded as a “single male”.

“I have access with the children and the Department (of Communities) is trying to give me the kids back but I haven’t been able to get the appropriate housing, so I’m stuck in a catch-22,” Craig explains. “Because I currently don’t have the kids in my care, (the department of) Housing is only offering me a bedsit when I do get on the (housing waiting) list.

“But I can’t accept the bedsit because to get the kids back I need a minimum two bedrooms.

“It’s very frustrating. People are trying to help me sort that out now. But I’m not holding my breath.”

Craig is one of Hobart’s increasing number of homeless, unable to find rental accommodation or public housing, which has a 3300-long waiting list. “I have a friend who lets me stay the weekends, that way I have access to my children on the weekend,” explains Craig, who says the girls’ mother is unable to care for them due to a drug problem.

“The rest of the time I visit mates. But you don’t want to use people or put pressure on people, so I end up just going camping with my swag and the dog, sometimes in the Queens Domain, sometimes just in any secluded place where I can be out of the way. I have had a lot of help from the Salvos but they are stretched beyond imagination.”

A disability support pensioner, Craig had done labouring work in the past but this had dried up.

Being homeless and without transport made it difficult to get to building sites.

He believes the estimate of about 140 people sleeping rough around Hobart is significantly understating the problem.

“Those numbers are more like 300, from my personal knowledge,” he says. “A lot of people have just given up putting their names down as homeless; you become numb to it all.”

Matthew Denholm

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout