Tale of four cities: some of old Europe’s best and worst

A northern summer holiday highlights some of old Europe’s best and worst.

On a recent family trip through four cities, I asked myself what Europe might be to us today.

Has it been reduced to little more than the West’s grand museum, a quaint series of curiosities for half-bored tourists trudging among a dusty repository of relics? Or does it continue to regenerate itself, providing examples of how to live well, catering to human pleasures and foibles, needs for innovation, and yearnings after things of beauty?

The cities were Rome, Barcelona, Paris, and London. Here is my tale of four cities, in snapshots from which I don’t want to over-generalise, for this is but one experience.

Rome’s faded grandeur

Rome is an ideal test case for the museum hypothesis. Although the seat of national government, it is largely a tourist mecca, with the more dynamic working and producing Italian cities such as Milan set well apart to the north. More, it offers layer on layer of significant history crammed in a hodgepodge of chaotic sites and vistas, ancient Rome elbow to elbow with the 17th-century magnificence of Bernini piazzas and fountains.

If Rome is a museum, it remains a teaching museum. The Rome of the ancients is in too poor a state of ruin to speak much today, apart from the Pantheon, and the Colosseum and the Arch of Constantine, both endlessly reproduced throughout the Western world in sporting stadiums and celebratory monuments such as the Arc de Triomphe in Paris.

It is 17th-century Rome that remains most potently alive with aesthetic effect. Cobblestoned squares, featuring ornate fountains with baroque marble statues, the relaxing play of water, surrounded by palaces and buildings with facades rendered in earthy oranges, ochres and creams, stone-framed doors and windows. The whole is cast with the hint of fading, flaking and cracking grandeur, that of the old and wisely matured, resonating with the charm of supreme taste. Here is an ageless lesson in design.

In St Peter’s Basilica, we stumbled into a German mass, conducted as if nothing had changed in hundreds of years, from the vestments of the priest, the rites of the Eucharist and the incantatory language of sin, damnation and redemption. The beauty of choir singing did little to offset the ambivalent feeling of being taken back in a time machine to a world that has completely gone, one of colourful, reverent ritual conducted in a sterile all-male preserve in obsolete language.

For me, personally, Rome is home to artistic masterpieces that never fail to engage and enchant. Raphael’s The Deposition in the Galleria Borghese sets the gold standard for virtuoso technique combined with deep and complex philosophical interpretation of the Jesus story and its wider, enduring meaning. In Rome also, one can idle off the street into the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi, to study Caravaggio’s The Calling of St Matthew, arguably the most profound evocation of what is involved in any person finding their life path, including its intimidating demands.

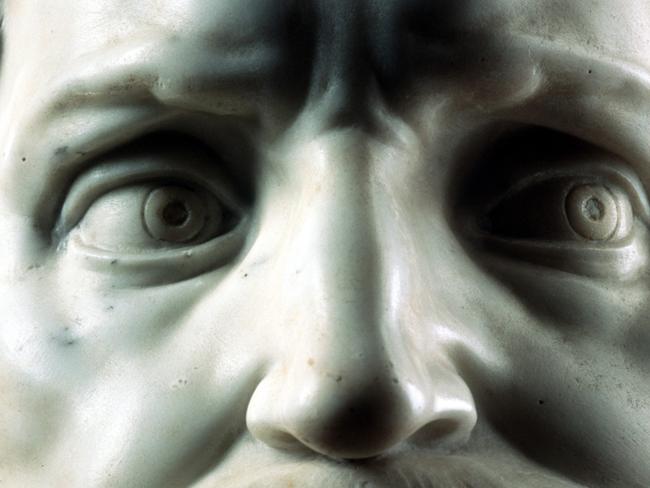

Similarly, in the Church of San Pietro in Vincoli near the Colosseum, one can wander into a side chapel to view Michelangelo’s most enigmatic finished work, his huge marble statue of Moses – a statue Sigmund Freud visited every day he spent in Rome, so perplexed was he by its meaning.

In a different key, the Bridge of Angels across the River Tiber invites the passer-by to gaze up and join Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s series of sculptured intimations of sacred connection.

Liveable Barcelona

Barcelona is utterly different. With nothing of the museum about it, it is the casual, holiday city – life conducted out of doors, youth its predominant company, hedonism its major key. Walker-friendly and accessible, from dense medieval lanes, incorporating contemporary design and fashion, to elegant grand boulevards that put the Champs-Elysee to shame, the city coheres. Beaches on the fringes provide summer respite, flanked by restaurants from which the idle diner can gaze out over the azure Mediterranean.

The city presents a visual symphony of wrought-iron balconies and stone facades. At home in the contemporary, its mood is one of ease and competence, pleasant and friendly, with no looking backwards. Perhaps today it should be awarded the prize for the world’s most liveable city.

Barcelona is, however, most profoundly, the city of Antoni Gaudi. His domestic architecture sets a playfully exuberant tone. Using spaces and materials as if wrung by a master contortionist, he evokes variety, novelty and surprise, a fantasia of beautiful stone, wrought iron, brick and mosaic.

At Barcelona’s cultural heart is Gaudi’s cathedral, La Sagrada Familia, still being completed 140 years after its beginnings. Its singularity opens with the premier of all cultural tasks, that of taking up the best works from the past and reworking them so they speak to the present. Here, the prompt is the medieval gothic cathedral, seen at its pinnacle in France, in Amiens and Bourges, with the driving principle that of using awesome internal height, projected by soaring stone columns, to lift the spirit of the mere mortal far down below up to God and his heavens, and reinforce faith in the eternal.

In Barcelona, Gaudi has reworked the archetype so his columns rise into fluted branches inclining to the centre to evoke the experience of a vast enchanted forest, closing way up above, over the head, light exploding in through beautiful stained glass from the sides, with the whole captivating with an elegant verticality, enabled using orchestrated and crafted stone, iron, marble and mosaic.

As with the French original, it is the internal spaces that command. Gaudi spent his last 40 years working on every minute detail of form, texture and material for his cathedral, often with brilliant engineering and architectural innovation.

Whatever one’s religious predisposition, or not, the experience of the Gaudi cathedral is breathtaking, uplifting, quite simply inspiring – one can only walk away indelibly affected. This is surely the peerless example of great modern architecture and design, equal to the best that has preceded it in the West. It achieves a timeless modernity that transcends its specifically Christian origins.

If German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche is right, that every culture is founded on a fixed and primordial sacred site, then Barcelona stands on firm ground, care of the Gaudi cathedral. One can almost sense the city stabilised around it.

But, in a final twist, as if scripted out of a Dostoevsky novel, the streets of impressively neat and clean Barcelona are pervaded in high summer by wafts of foul odour from the sewers.

Paris trapped in past

Paris was in total contrast. From airport arrival on, the tone was set by bad-tempered taxi drivers seeming to resent their customers.

In central Paris, the shock of the old immediately hit home – the weight of what has come before. It is all there, very fine and distinguished, but stiff and formal, in boulevards, monuments, solid apartment buildings emblematic of a high bourgeoisie content in its symbols of eminence and consequence, kept afloat by nostalgia for the grandeur of a distant past when the Sun King, Louis XIV, then Emperor Napoleon, dominated Europe and French could claim some of the trappings of being the universal Western language.

Likewise, a century after Napoleon, Paris was the world centre for the avant-garde in art, literature, and philosophy. But today no young and ambitious Picasso, Joyce, Hemingway or Orwell would – in search of the energy and imagination of the new – bother to relocate to Paris. Picasso’s Montmartre retains its charm, but the art there is slick portraits of passing tourists, with the flavour of its past best caught at a remote distance, in Moulin Rouge!, Baz Luhrmann’s 2001 Australian film.

Perhaps a chill has spread from the French language itself. The straitjacket of its grammar produces a classical precision and elegance when the language is spoken well but closes it off to innovation.

A similar fate has rendered French vocabulary small and static, and vulnerable to the direct importation of hundreds of English words, much to the chagrin of French purists.

One marker of significance to visitors is that cafes all have the same narrow menu, with the quality of food these days mediocre at best in this traditional area of French strength. It seems the locals no longer care. Even the esteemed Cafe de Flore, in St Germain des Pres, shows little interest in reforming its turgid coffee, too self-assured in its closed-minded ways to learn from Italians or Australians.

French conservatism, which is pervasive, and excellent at preserving the past, has a stifling side, turning its back on experimentation, remaining closed to what might be different and new. Further, a centuries-long tradition of bureaucratic centralism imposes a mandarin canopy of regulation that inhibits innovation and induces entrepreneurial passivity. Enervation shows in declining quality and failure to modernise.

On Sundays, almost everything is shut in central Paris – an unpleasant reminder of Australian cities 40 years ago. Some strain of cultural torpor prevails here. I am saddened by this conclusion as I used to savour going to Paris – today, the glamour is off.

The odd flicker of ancient greatness can be seen occasionally, for instance in the Musee d’Orsay, a railway station transformed three decades ago into the magnificent art gallery exhibiting French works between 1848 and the start of the 20th century, a golden age including the paramount collection of impressionist paintings.

If Brexit ends up, on balance, damaging Britain, its toll may be even heavier on France, in accentuating insularity and distance from Anglo dynamism. We live in a world in which virtually all major technical and cultural innovation comes out of the US.

In relation to another sociological feature of contemporary Western social life – multiculturalism – the French also have failed badly.

Paris is not monocultural but its other ethnicities and subcultures largely have been banished to banlieue ghettos on its outskirts, turning them into seedbeds for Islamist terrorism. In providing a case-study in how not to integrate immigrants, the French have created long-term challenges for themselves. One consequence has been the political rise of Marine Le Pen and xenophobic nationalism.

On the question of Europe as museum, there remains the fact that the Louvre, arguably the greatest of all cultural repositories, continues to welcome millions of visitors a year into its pleasant and efficient, vast and once royal spaces.

Many continue to find engagement and inspiration in the countless supreme masterpieces housed there, including, to name a few, the Winged Victory of Samothrace, Raphael’s La Belle Jardiniere, Johannes Vermeer’s The Lacemaker, Georges de la Tour’s Joseph the Carpenter, Caravaggio’s Death of the Virgin, Nicolas Poussin’s The Four Seasons and many other of his major works, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s Oedipus and the Sphinx, Eugene Delacroix’s The Massacre at Chios, and even Leonardo’s Mona Lisa.

London buzzing

On to London, and impressions took another twist. The genteel elegance of the Paris boulevard was gone as we were pitched, in central Soho, into the hustle and bustle of a seething mass of perhaps the most multicultural crowds to be seen anywhere on Earth – and multicultural businesses, starting with all types of food outlet. Here was energy, hubbub and movement – the buzz and fizz of a great city.

London has gone in the opposite direction to Paris. In Soho, the old seediness is no longer to be seen and with it the stodginess of English food. Who could imagine there would come a day when London had better cuisine than Paris?

The key is the centuries-old English tradition of openness to the wider world, in the language as in journeys of exploration, as now in the living. The liberal individualism that pulses in the cultural veins, that has most notably fed into the two great English contributions to the modern world – parliamentary democracy and industrial capitalism – remains a vital presence on the London street.

Liberalism, in its innate hostility to the tribal and the bureaucratic, provides the cultural template for innovation, encouraging the ambitious entrepreneur and the potential customer. In Soho, the result is a kaleidoscope of boutiques, eateries and food shops.

This teeming maelstrom is balanced by the solidity of familiar London anchored in the timeless, imposing quality of its institutions. The grid of imperial Britain is omnipresent and speaks of a great past that secures the present: Houses of Parliament, Big Ben, the Tower, Trafalgar Square and Nelson’s Column, Waterloo Place, Piccadilly Circus, Buckingham Palace, and Marble Arch, but also the British Museum and the National Gallery. There is grandness and gravity here, difficult for our present age to emulate, a weight that easily might be resented by a present that feels itself, in comparison, diminutive.

My suspicion is that here lies the Paris problem. But it is no less of a challenge in contemporary London. The British Empire is over; great scientific and technological breakthroughs hardly come out of England any more; and the UK is reduced to but a middling world power.

To progress, Britain cannot dwell on the world it has lost, consoling itself with Downton Abbey period drama or recapitulating heroic moments from World War II. It must reinvent itself now that its long post-war melancholy seems to have lifted.

On the question of museum culture, two of London’s premier institutions, the Natural History Museum and the Victoria and Albert, champions of optimistic Enlightenment progress, are dated, faded dowagers.

The former is housed in a grand 1881 simulation of a gothic cathedral, with a statue of Charles Darwin where the altar would be, a fitting homage to the messiah to the new religion of science and reason. The collection contained within is static and dull.

The Victoria and Albert Museum, built in 1852 to collect in one place the achievements of industry from all nations, an admirable ambition, is today a chaotic jumble of bits and pieces, of limited relevance in the age of cable television documentary and Google.

Among other random snapshots, we saw a magical piece of theatre, Matilda the Musical, which has been running in the West End for more than a decade. The Dionysian, wild creative vitality of the show, with a five-year-old girl as saviour, seemed to epitomise the London we were experiencing.

A reinvented London will express itself through traditional strengths such as theatre. Close by, the phenomenally successful Harry Potter and the Cursed Child was in full swing, a British creation like its parent story – in both seven-volume book and brilliant eight film series.

I could not return to London without visiting the Churchill War Rooms. There is, arguably, no more significant 20th-century moment than the 1940 British repulse of Nazi attack, inspired and directed by Winston Churchill’s leadership, without which Adolf Hitler would likely have won, leading to a different and more malign world.

Britain has shown resourceful adaptation since the Middle Ages, with a long history of throwing up leaders when needed. The positive reading of Brexit would cast it as an eruption of the people’s liberal individualist instinct, telling them they do best when on their own. It would, I think, be premature to disregard this.

The visit to London occurred just before the death of Queen Elizabeth II. The world response to the public mourning and funeral, and the accession of King Charles III, suggests Britain still has a primary role to play in signalling the importance of venerable institutions to a stable body politic — a conservative riposte to the liberal.

The focus on four cities requires some qualification. For instance, much of Britain, as always, is not like London. Barcelona has an independent Catalonian esprit, in contrast with the dour Castilian mood of Madrid and much of the rest of Spain. Paris has its own demons to tame. And Rome is quite unique in its resilience and charm.

In relation to my opening question – setting aside the enduring spell cast by Rome – Barcelona and London have little of the feel of a tired old European museum.

John Carroll is professor emeritus of sociology at La Trobe University.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout