Taiwan’s ‘Nelson Mandela’ remained uniquely independent until the end

The uncompromising Shih Ming-teh spent half his life in jail fighting to achieve genuine democracy in his threatened homeland.

OBITUARY

Shih Ming-teh

Dissident and politician. Born Japanese Taiwan, January 15, 1941; died Taipei, January 15, aged 83.

On January 13, the brave people of Taiwan voted for the Democratic Progressive Party’s bold William Lai to take on the presidency of the Republic of China as it faces an unprecedented threat from its menacing neighbour, the colossus known as the People’s Republic of China.

The Communist Party that rules the mainland Chinese must have a dark sense of humour: in any republic the people, and those for whom they vote, are the supreme power. In the People’s Republic of China it is the dictator Xi Jinping, and he rules over more almost 1.5 billion people; Lai will take over a remarkably dynamic nation of just 24 million.

The world has long been impressed by the educational and technological revolution of the island nation that in less than 60 years has elevated its people from a rural backwater to one of the world’s most highly developed economies.

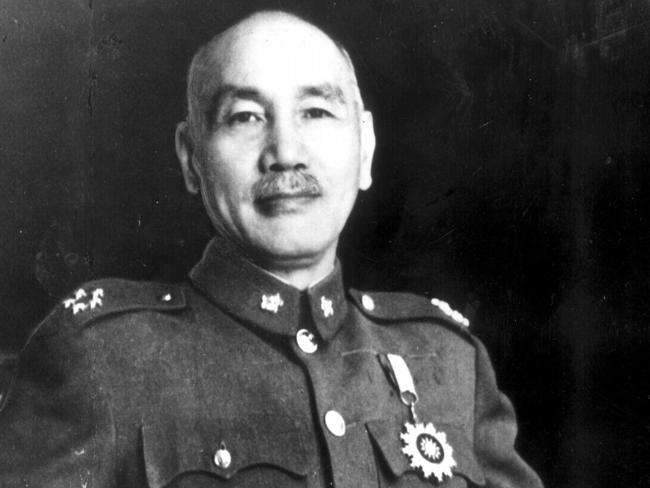

But the sophisticated democracy we see today came at a serious cost. When the Kuomintang government of the Republic of China fled the mainland after the communist victory in 1949, its leader Chiang Kai-shek was trying to build an economic homeland in Taiwan, which had been under Japanese control, while dreaming of retaking the mainland. It was effectively a one-party state. From May 20, 1949, until July 14, 1987, Taiwan was under martial law, an era of political, social and media restriction unimaginable today.

But Taiwan has always thrown up bold men and women who would sacrifice everything, even their lives, if it helped deliver democracy to the island.

Perhaps the bravest of these was Shih Ming-teh. He had been born there in the final years of a typically brutal Japanese colonial administration. Japan’s surrender and the arrival of the Kuomintang might have seemed good news, but was equally repressive in many ways.

Shih failed his university entrance exams and joined the army but was quite public about the fact he wanted to overthrow the government and deliver real freedoms to the people he saw as his, more than any mainland refugee might. He and his brothers were arrested in 1962 for being part of an independence campaign. Between then and his conviction as one of its leaders in 1964, Shih was beaten, his teeth smashed and his spine cracked.

In prison he studied history, international law and philosophy. But any unrest in the prison system was blamed on him, and sometimes that was right. He was held for years in isolation after an uprising in 1970.

In 1975 Chiang died and two years later his more practical son released Shih. He immediately became a leader of the democracy movement, and when it was murderously put down in 1979, Shih went on the run. He was captured the following year and jailed for life again, along with many rebels and journalists.

With the end of martial law he was offered his freedom, but with conditions he rejected. He and his brother went on a hunger strike. Shih’s weight fell to 45kg; his brother died. Finally, his trial was ruled invalid and the newly free Shih joined the Democratic Progressive Party and won a seat in parliament in Taiwan’s first completely free elections in 1992.

The outlier was considered dangerous but said Taiwan was already free; it did not need to announce its independence. Not comfortable with the confines of party rules, he resigned and briefly sided with the nationalists who had jailed him before running as an independent. He ran for president on the platform of making an agreement with the mainland that they would run the two Chinas as one entity, but do so independently.

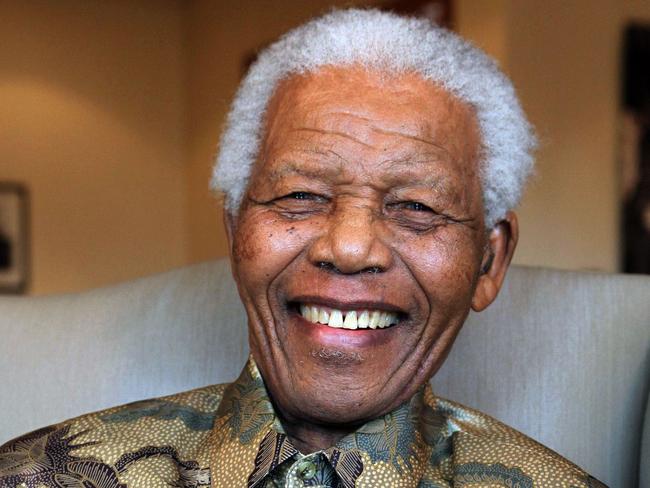

After so long in jail, Shih inevitably was referred to as the Taiwanese Nelson Mandela.

The government of Taiwan, always on the lookout for friends, invested about $15m in the campaign of the African National Congress when South Africa went to its first post-apartheid elections in 1994.

On assuming the presidency, the almost universally acclaimed Mandela proposed a unique solution to his country’s new dilemma. South Africa would recognise both Chinas. Mandela’s country was just one of 29 that still maintained full diplomatic relations with Taiwan. Mandela believed he might assist in bringing the two together with his unique proposal and benign influence.

The bullying Chinese Communist Party made South Africa’s various representatives quite aware that unless they abandoned Taiwan, the new democracy would lose its “most favoured nation” trade ranking. Mandela held off for two years but caved into the inevitable. Shih would never have done that.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout