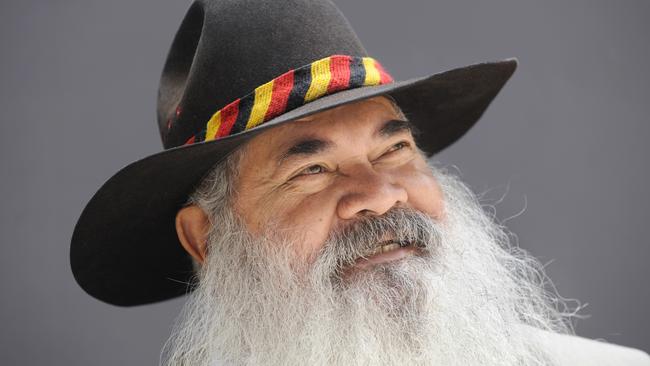

Successful voice a vindication for Australians who advocated for Indigenous people before they could advocate for themselves

A successful Indigenous voice to parliament vote would honour Australians like the Gartlans, says Pat Dodson.

Pat Dodson was an orphan when he arrived at Monivae College in rural Victoria on a scholarship. In the seat directly behind him in class was Tony Gartlan, the son of Chetwynd sheep farmers Jack and Marion Gartlan.

“I was sitting at my desk and this young fella behind me poked me in the back with a ruler and I turned around and he asked whether I had a sharpener because he needed a sharpener to sharpen his pencil and I said, ‘Well, here you are mate,’ ” Dodson tells Inquirer.

“And the priest who was up the front when I turned around said to me: ‘Are you talking, son?’ And of course I said yes. And he said: ‘Step out.’ And I had to step out and I got four cuts across the hand for talking to the kid behind me.”

Dodson remembers Tony soon invited him to the family farm for the school holidays. “I said ‘yeah’, otherwise I’d be stuck at the college,” Dodson says.

“So I went up there and me and him became mates … and I got friendly with the rest of the family and spent most of my school holidays up there on their farm during the six years I went to Monivae College.

“It started from that conversation. They are lovely people.”

Dodson’s parents, Snowy and Patricia, died in 1960, when he was 12. It was Dodson’s younger brother Mick, then 10, who found their father with a gunshot wound to the head. According to Kevin Keeffe’s 2003 biography Paddy’s Road, police said the death appeared to be suicide but the family was unconvinced. Patricia died a few months later when she slipped and fell from what was then a narrow Katherine bridge. She had been trying to step out of the way of an oncoming car.

Family took care of the five Dodson siblings. Dodson was sent to the Catholic boarding school in Hamilton, Victoria, on a commonwealth scholarship administered by Missionaries of the Sacred Heart, which is where he met the Gartlan family.

Dodson sees his friend Tony’s mother, Marion, as a hero. She stuck up for him. He has come to regard the voice referendum as a form of vindication and honour for Australians like her who advocated for Indigenous people before they were able to advocate for themselves. She once intervened to ensure Dodson did not have to submit to regular welfare checks.

“She was a pretty formidable lady. But very generous, very loving. And obviously had a great deal of affection for me,” he said.

The Gartlans are a powerful reminder to Dodson about the goodness of Australians.

Long before the term was coined, the Gartlans were probably what is now known as allies.

“The welfare back in those days used to have to come and check whether you even had sheets on the bed,” Dodson says. “So they would assess your progress and check to see … there were some positive things about it, but they were intrusive in your life.

“And constantly reviewing how you were going so you never had a chance to breathe because you were constantly thinking that you’ve got to measure up to their standard, it was all part of the assimilation policy. If you weren’t conforming to what they required then you’d be ticked off about it. You’d be given some counselling to go in a different direction.”

That is where Marion came in. Before then, Dodson’s understanding of how white and black Australia interacted was not comforting. He saw police bearing down on Aboriginal people in his hometown of Katherine and he saw the Gurindji stockmen in a seven-year dispute with the Vestey Brothers at Wave Hill. Marion’s love, compassion and action was a revelation.

In a short meeting at Dodson’s school between Marion and a welfare officer from Melbourne, it was agreed Dodson would no longer be subjected to regular checks.

“(The Gartlans) knew what stupidity this was, and they knew far more than I knew about the background of assimilationist stuff, and they had far greater integrity in the relationship with me than the welfare system,” he said.

Dodson was not living with the Gartlans at the time but Marion and Jack drove 94km from the family farm to Dodson’s college to have her say that day.

“That (welfare officer) was removed because of the courage and strength of Mrs Gartlan when I was in second form secondary school, and from there the goodness of people, the goodness of non-Aboriginal people dawned on me or drove a deep commitment into me that there was goodness,” he said.

“It wasn’t all the bad things that I’d seen as a kid.

“If we have a successful outcome in the referendum, that would give honour to those people who over a long period of time have been supportive of Aboriginal people, who have advocated on our behalf when we were incapable of advocating for ourselves – who stood up for us, who helped us in so many ways.”

The Gartlans have died. Their son Tony, Dodson’s school friend, died 30 years ago. Dodson, now 75, remains close with Bud Gartlan, Tony’s older brother. Bud is 82 and retired in Portland, where he says the wind “blows the milk out of your tea”. Bud refers always to Dodson as Paddy and “my brother in Western Australia”. Dodson calls Bud “my brother in the south”.

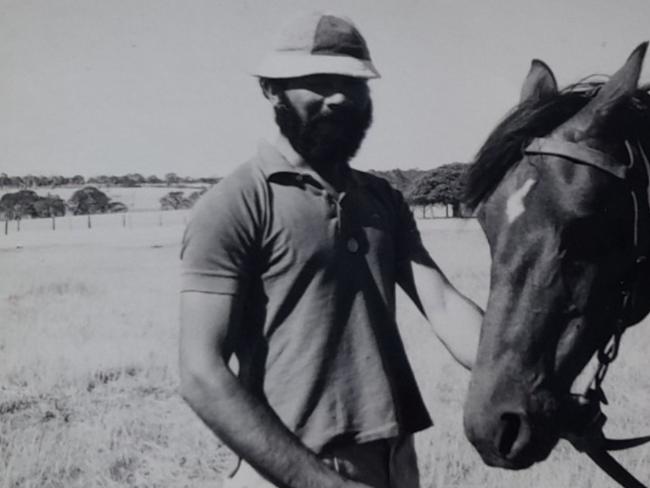

“He came down from Katherine or wherever it was in about ’63 and I was working on the farm at home, you see, I left school the end of ’58,” Bud says.

“He came out to our place for weekend and holidays, and he just became another brother of mine.”

Bud knows Dodson has long been a public figure, is the father of reconciliation and a household name because of his work as a lawyer, as an Indigenous leader, as a commissioner examining deaths in custody and as a Labor senator. The pair rarely discuss politics. They talk about family and football.

“I didn’t know any Indigenous people at all when I met Paddy,” Bud says. “Only time you saw them was when they were at the boxing tent at the shows. So it wasn’t strange to us but it was just different, yeah.

“The fact that he was not white did not matter to us. And my mother was a very charitable lady, and all of us were, but she was especially. She just accepted him for what he was, not his bloody colour or anything.”

Dodson is recovering from treatment for Hodgkin’s lymphoma diagnosed just as the campaign for an Indigenous voice to parliament took shape. He hopes he will be well enough to campaign before referendum day on October 14.

Bud says Dodson has never pressured him to vote for the voice. He is candid that he does not know much about it. “I don’t really know what it is,” Bud says.

This is evidently the challenge, or the opportunity, for the Yes campaign.

Bud’s relationship with Dodson is all about the personal. He knows Dodson has often arrived at family gatherings straight after big conferences or political events. Dodson does not boast about his work or influence. The men do talk about their memories of old times, and Bud knows that Marion’s decision to get between Dodson and the welfare officer 60 years ago had a profound effect on his friend.

“Once the old girl had a go at him (the welfare officer) he never come back, that sums it up,” Bud said.

Dodson sees the voice as advocacy and responsibility. It will be an “astronomical” change in the relationship between Indigenous people and the government. In short, Indigenous people could be held to account for policy failures and successes in a way they cannot be held responsible now since they have no meaningful say.

“The solutions to these problems can be advocated for on behalf of them by their own entity called the voice who can make representations to the parliament and to the executive,” Dodson says.

“There is no obligation on the parliament to accept that but there is a clear nexus between the Aboriginal people’s capacity to make their own representation, make their own representations, carry their own burdens around responsibilities and to present their arguments to the parliament and the executive in their own right and be accountable for their advocacy rather than anyone else.

“I mean, how great a thing than to give people their own responsibility to bear their own burdens and to assist them in getting the outcomes that are critical to the quality of their lives, and that’s what we’d be enabling our future generations to be able to see in practice. What a great bequeathing that would be by us.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout