How Palestinian supporters weaponised the Holocaust for their PR war

Protesters have misappropriated the Jewish death camps to accuse Jews of being Nazis and Israel of committing genocide in a cynical ploy designed to bolster their narrative.

At the tent encampments of protesters at American universities, posters and placards proclaim the Israeli genocide of the Palestinians and the complicity of diaspora Zionist Jews – in genocide, Jews, who were once the victims of Nazis and are now Nazi victimisers. Many of the protesters do not look like students, especially those who smashed their way into an administration building at Columbia University in New York. They look like thugs. Full of hate.

At the University of Sydney on Thursday last week, on Anzac Day, at a small tent encampment, with the inevitable placards about Israel’s genocidal war against the Palestinians, children were led by adults in chants calling for intifada and declaring Israel haram – a forbidden state – and a terrorist state. Nazis, right.

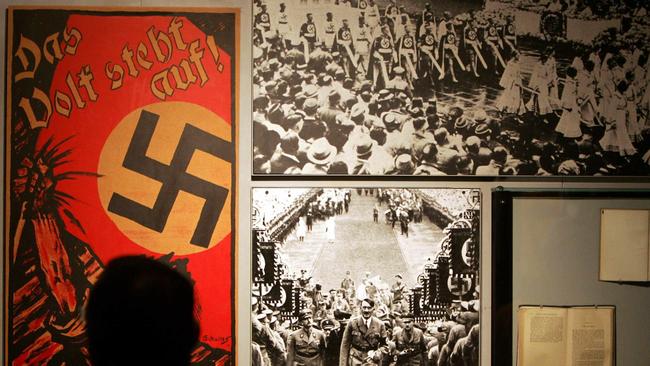

Every week since the Hamas massacre of 1200 Israelis and the kidnapping of more than 250 men, women and children on October 7 last year, in Sydney and Melbourne and London and New York and scores of other cities across the Anglosphere in particular, hundreds of thousands of people march in pro-Palestine – and increasingly pro-Hamas –demonstrations. In these demonstrations, placards with a swastika engulfing a Star of David and placards of Benjamin Netanyahu as Adolf Hitler are commonplace. Unremarkable. The Jews are the new Nazis: that notion is no longer startling or, for many people, troubling.

Jews and Nazis. In London, city officials have decided the Holocaust memorial in Hyde Park needs to be covered up by a big blue tarpaulin every weekend because if it is left uncovered it would likely be defaced by pro-Palestine marchers. There is surely something deeply unsettling about this, this symbolic erasure of the Holocaust to assuage the feelings of those marchers who are sick of having the Jews use the Holocaust to excuse the genocide in which they are apparently complicit.

Even before October 7, some anti-Zionists, including Jewish anti-Zionists, were prepared to say there were similarities between Israel and Nazi Germany. The Holocaust had been universalised. It had lost its Jewish particularity.

It could have happened to any people, this attempted genocide, and the perpetrators could have been, in the right circumstances, any people, including, inevitably, Jews. When Whoopi Goldberg said the Holocaust was not about racism but, rather, about privileged white people committing terrible violence against each other, she was – crudely, perhaps – expressing a widely held position on the anti-colonial left: Only black and brown people can be victims of racism and Jews are quintessentially privileged whites. White oppressors.

The Israelis as genocidal racists is now a truism in the university encampments, among the thousands of pro-Palestine marchers, many of them regularly quoted in the media about Israelis as Nazis, perpetrators of a genocide.

For the anti-colonial left, for the social justice warriors who divide the world between victims and oppressors, the Holocaust is what the Jews, the Zionist Jews in particular, the colonial oppressors, cynically use to justify their Nazi-like oppression of the Palestinians. That’s the Holocaust for the pro-Palestine, pro-Hamas left.

But the Holocaust now has many meanings. It has become a symbol of different things to different people, its meaning, its place in history and its contemporary significance increasingly a matter of politics and ideology.

There have been great Holocaust histories written and there have been thousands of testimonies given by survivors and books written by magnificent writers such as Primo Levi, who was an Auschwitz survivor and who wrote about life in Auschwitz with such brutal honesty and clarity.

None of this seems to matter, none of this seems to inform those who use the Holocaust for their own political ends. There are anti-Zionist Jews, for instance, the “I am speaking as a Jew” anti-Zionist Jews who constantly refer to the fact they are the children or grandchildren of Holocaust survivors. This somehow gives them a moral clarity about Israel and the Palestinians – who are the victims and who are the victimisers – that Zionist Jews do not possess.

They have a special duty, in the name of the victims of the Holocaust, in the name of their relatives who were survivors, to call out the Israeli genocide against the Palestinians and advocate for the end of the Jewish state.

At a small Holocaust commemoration event on April 19, the date in 1943 that marked the start of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, a small group of young Jews stood outside the hall with placards designed to shame those inside, including Holocaust survivors. Their placards had slogans on them about the Gaza genocide and about the silence of the Jews inside the hall commemorating the genocide of the Jews of Europe.

Then there’s Jonathan Glazer, whose film The Zone of Interest won the Oscar for best foreign film at the Academy Awards in March. In his acceptance speech he said that his film, which is set in Auschwitz, in the home of the camp commander and his family, “showed where dehumanisation leads at its worst”. He then went on to say: “Right now, we stand here as men who refute their Jewishness and the Holocaust being hijacked by an occupation which has led to conflict for so many people.”

If you can work your way through the clumsiness of his words, speaking as a Jew, the director of a much-praised film about the Holocaust says to a worldwide audience of millions of people that the Holocaust is being used by Jews to justify the occupation and the war in Gaza. Indeed, more than that, the Holocaust is being used by Israel to justify its genocidal aims.

The Holocaust has come to mean different things to different people. If for sections of the left Jews have become Nazis, many Jews, for understandable reasons, have come to regard every antiSemitic act, large and small, as evidence that another holocaust is possible, if not inevitable.

For them, Hamas are the new Nazis and the Hamas pogrom of October 7 was the worst pogrom against Jews since the Holocaust. This may be literally true, but what is not true is the implication that it was Holocaust-like, and that Hamas are the new Nazis.

But not every expression of Jew hatred or even violence against Jews needs the invocation of the Holocaust and the warning that it is to a Holocaust that Jew hatred almost inevitably leads. It does not.

In many ways, the Holocaust was a singular event, a genocide committed in the heart of Europe. And not all anti-Semitism or Jew hatred is, like Nazi anti-Semitism, eliminationist.

The Holocaust means different things to different people. It has become a profoundly profitable subject for popular culture – for bestselling books and films and even blockbuster television series.

Last week, a venerable Jewish news organisation ran a large paid advertisement for a new Stan series. These ads have been sent to all Stan subscribers. There are even billboards of the ad in some neighbourhoods.

The ad is a good piece of work. It is an arresting image. Two people in the striped grey and blue uniforms of Auschwitz up against each other, one wearing a dirty yellow Star of David to signify that these are Jews.

Only their torsos and arms are in the image – they are faceless, headless, but look down and the uniformed Jewish torsos have arms and hands, radiantly lit hands, filthy hands and fingers and fingernails. But their hands, their dirty long-suffering hands, are in an embrace, their fingers entwined, with love, heaven help us, with love here in this place of death and darkness and depravity.

This image was created, we must assume, by the talented artists employed by Stan – it has the feel and power of a photograph of real hands and fingers – to promote its blockbuster series, The Tattooist of Auschwitz, released worldwide on Thursday.

It is a special series. Barbra Streisand has had a special song written for her for the series and when asked why she has done this, recorded a theme song for a television series, she was quoted as saying that at a time like this, we need hope that even in darkness, even in the hell of the Holocaust, there is love.

The series is based on the novel The Tattooist of Auschwitz, which was published in 2018 by New Zealand writer Heather Morris who had formed some sort of a relationship with an old Melbourne man, a Holocaust survivor. In Auschwitz he had been given the task by the Nazis of tattooing designated numbers on the forearms of Jews.

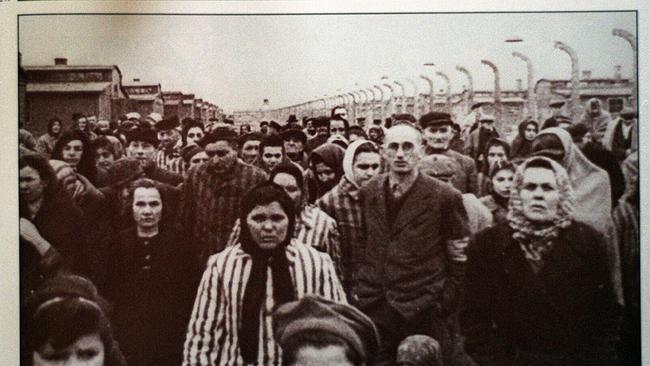

These were Jews who when they were disgorged from the cattle trains were not immediately sent to death in the gas chambers but instead were chosen for slave labour. The vast majority of them would be gassed before Auschwitz was liberated by Soviet soldiers in January 1945.

The tattooist was one of those Jews and had it not been for the research work and interviewing skills of Morris he would have remained one Holocaust survivor among many in Australia. What she discovered was that he had tattooed the number on the arm of a young woman with whom he subsequently fell in love, there in Auschwitz.

Given that the Stan series has just started, it would be unfair to reveal how this love apparently blossomed and grew and became a physical reality and then spanned decades and continents. But given that the book has been translated into 47 languages and sold 12 million copies, with many more to come in the wake of the Stan series, it is fair to assume that neither the book nor the series ends unhappily for the tattooist or the girl he tattoos. Love in a death camp that ends happily.

The book was widely criticised for its fabrications and distortions – the Holocaust survivor and the girl he loved were dead by the time the book was published – by the Auschwitz Museum and by Holocaust historians, to which criticism the publishers responded by pointing out that the book was a novel, a work of fiction, not history.

There are increasing numbers of books and films and now TV series such as this, set in the Holocaust – in some ghetto or death camp―where love somehow manages to exist and grow or where despite the reality of crematoriums burning bodies every day in their thousands, gassed bodies, people retain their humanity and their hope. Holocaust love stories, most of them. Terrible fables. In truth, Holocaust-denying fables.

Holocaust fables that sell millions of books and are then made into blockbuster series for which a Jewish liberal icon, Streisand no less, sings the theme song – a Holocaust love story with a theme song no less.

English writer Howard Jacobson wrote this when The Tattooist of Auschwitz was published: “Auschwitz today is a tourist destination, whether you mean to go there by train and come back with a trinket or travel to it between the covers of a book. It has even spawned a popular subgenre – the Auschwitz novel. Auschwitz Lullaby, The Child of Auschwitz, The Librarian of Auschwitz, The Druggist of Auschwitz, The Tattooist of Auschwitz, The Chiropodist of Auschwitz. Only one of those is made up by me, and who’s to say it isn’t being written this minute?”

Was this takeover of the Holocaust by kitschy fiction and film and television inevitable? Is that what it has become and will increasingly be, a site for pop cultural exploitation?

The Holocaust Museum in Melbourne is not a tourist destination. Recently rebuilt and remodelled, it is the most imposing and significant-looking Jewish building in Melbourne, possibly in Australia. It does not traffic in Holocaust romances. It is dedicated to remembrance and to education. It believes there are lessons about the Holocaust that can be taught.

To this museum come thousands of Melbourne schoolchildren each year for organised tours where they are given talks by volunteers, some of them Holocaust survivors though fewer and fewer survivors are still capable of volunteering in this way. The museum provides educational material for Victorian schools where students in years 9 and 10 in state schools study the Holocaust as part of the history of World War II.

What are they taught? What agreed truth, at a time like this, when the truth about the Holocaust, its meaning, is contested, can these young people be given? It is hard to see how Holocaust education can work, what it can actually achieve – even what it should and can aim to achieve. What, for instance, is the nature of Holocaust education in state schools in the northern suburbs of Melbourne or in Sydney’s western suburbs where a significant number of teachers are proudly pro-Palestine and opposed to genocidal Israel and have urged students to attend pro-Palestine marches? What do they teach about the Holocaust?

Huge amounts of money have been spent on Holocaust education and on the building and maintaining of Holocaust museums and memorials in many countries in Europe and South America and Canada and the US and Australia. What is their purpose? What stories do they tell? Brutally speaking, what good do they do?

The evidence of history is that hatred of the Jews is not a matter of a lack of education. Some of the most virulent and murderous Nazis were academics, renowned philosophers, venerated political scientists, not to mention hordes of judges and scientists. Can education work when the truth and even the facts are contested, when what is real is contested? What then should Jews like me do?

This Sunday night, in Sydney and Melbourne, there will be communal Holocaust remembrance evenings. These events are held annually in Jewish communities around the world on the 27th of Nisan, the date on the Jewish calendar that corresponds as closely as possible to April 19, the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Hundreds of Jews in each city, perhaps thousands, will attend the evenings. No doubt there will be security arrangements in place.

They are evenings of remembrance. Honouring the lives of the millions of victims. Honouring the cultures that were destroyed, the darkness that befell the Jews of Europe. Remembering is what Jews do well. Tisha B’Av is an annual Jewish day of mourning, centuries old, with its own liturgy that marks the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem almost 2000 years ago. Remembering, that’s all. And that’s enough.

Looking at the programs in both cities, a Holocaust survivor will be the main speaker in each city. Songs will be sung. Some of the songs in Melbourne are of poems written by a poet whose family perished in the death camps, poems put to music and sung by a band of young Jews.

Six candles will be lit, one for each million Jews murdered by the Nazis. The theme of the Holocaust remembrances this year is We Are Here, which is a line from the Jewish Partisan’s Song that is sung at the end of every remembrance event. The song is sung with gusto. It has been sung with gusto ever since it was sung in ghettos and in displaced persons camps after the war. It is a song about memory.

In a way, it is a version of lest we forget. What happened and what was done.

Michael Gawenda is the former editor of The Age and is the author of My Life as a Jew.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout