Strategic budget fires starter’s gun for election

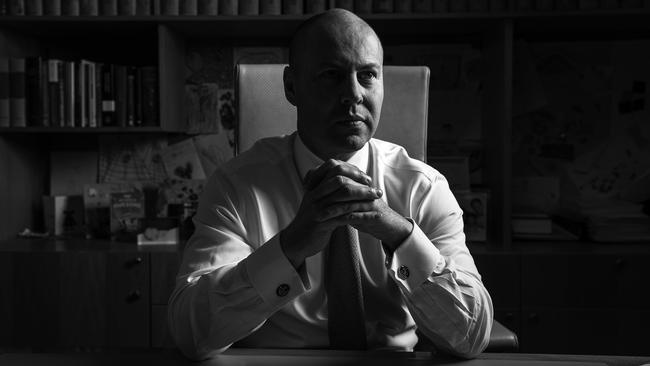

Josh Frydenberg’s strategy is economically audacious and politically easy. But who will be in charge when the reckoning arrives?

Scott Morrison and Josh Frydenberg have defined the parameters for an extraordinary re-election campaign that will be dominated by two themes: health and economic security.

This is a pandemic-framed budget and the government wants a pandemic-framed election.

With Morrison declaring an ongoing “raging pandemic”, the government is borrowing from the pandemic protectionism of the premiers and plans a closed-borders re-election campaign, with its budget saying that the international border will not reopen until mid-2022.

The unifying theme of the Frydenberg budget is “securing the recovery” by inaugurating a prolonged spending agenda to deliver more jobs, a growth economy and a renewed social compact. The core message is that more spending equates to more security. Every road leads back to the idea of security — at home, at work, and at leisure.

The Morrison/Frydenberg mantra is that in a dangerous world, Australia must protect its success in fighting COVID and guarantee a robust economic recovery unmatched so far across the industrial world. The government plays to the cultural transformation in Australia driven by the pandemic, with the public demanding more from government — a strong health system, hard borders and more spending, with a mentality that is risk-averse, protection-orientated and focused on Australian sovereign performance and a deeper awareness of family life and loyalty.

“We know the job is not done,” Frydenberg said. “We are still in the middle of a pandemic.” The government sees a world changed fundamentally by the virus. It seeks a new normal post-pandemic. But it has two vulnerabilities — getting the vaccine rolled out by year’s end, and strengthening the quarantine system.

The entire edifice rests on the vaccine rollout. The jab is the ultimate personal security assurance. Morrison began the year inviting the public to judge him by the vaccine delivery. He cannot risk an election without the vaccine rolled out across the population — and that points to an autumn 2022 poll.

The Frydenberg strategy is fuelling a hot economy — surging growth, lots of new jobs, growing labour shortages, strong consumer spending, more borrowing, and higher asset prices all operating in the febrile, artificially closed economy with no international travel and negative migration. This is a unique experiment in stoking up demand amid constrained supply.

The business community welcomed the budget but is worried about Australia’s strategic setting. In her interviews, Business Council of Australia chief Jennifer Westacott said there wasn’t “enough ambition” for the post-pandemic economy in which Australia needs higher growth outcomes, advanced skills, the ability to live with reopened borders, and business investment to deliver not the old economy but a better economy.

The Frydenberg budget is far more than an election sugar hit. If this is how you see the week’s events, you don’t grasp what is happening. The strategy envisages spending levels running for a decade at a steady level projected to be 26.2 per cent of GDP in 2031-32, with the budget still in deficit at this point. This level of spending is higher and for much longer than in the Rudd/Gillard era, famed for Coalition attacks on its government extravagance.

The Labor Party has not faced a Liberal government like this before. It has not faced a Liberal government that has relegated fiscal repair to a third-order priority, aspired to create a new Morrison/Frydenberg social contact, and ditched the prized Howard/Costello economic policy that operated in a different climate. For this reason, Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese was right to play it safe in his budget reply.

So where does Labor go?

It hasn’t finalised its stance but it has three options. First, to repeat Kevin Rudd’s 2007 tactic as a fiscal conservative against John Howard’s big-spending election agenda. That worked for Rudd in 2007 but it won’t work for Albanese in 2021 because the pandemic has legitimatised Keynesian stimulus.

Second, Labor could follow tradition and offer more spending than Frydenberg. But that would be pointless. It would ignore Bill Shorten’s blunder in 2019, and it would diminish Albanese as an even bigger spender while winning no electoral kudos in the process.

That leaves the third option — staging a contest over the future shape of a reinvented economy. This means saying the country cannot revert to nostalgia; talking about superior public intervention than the Liberals, more value for money, better government, promoting the digital economy, clean energy, renewable investment, social housing, a skilled workforce, secure jobs, outlawing wage theft, productivity reforms, championing equality for women, more childcare, and ensuring that “no one is left behind”.

This is a difficult position to devise, brand and market. It reveals the extent of the tactical conundrum facing Labor. But it is probably the best summary of where Labor is heading.

Labor’s dilemma is that the pandemic crisis has brought the two parties closer together on broad economic policy, as revealed by the budget.

Albanese’s challenge is to offer a distinct Labor framework that cuts through, giving people a positive reason to vote Labor beyond his attack on Morrison’s failings. The danger for Albanese is apparent — excessive caution. He has been astute in eliminating Shorten’s “big target” mistake from 2019 but ineffective so far in establishing his own brand.

This is complicated where the public is shunning radical change. It wants security, protection and reliability. It wants the vaccine rolled out and the economy ticking over.

Albanese knows the election will be fought on economic and COVID recovery, not the chosen progressive agenda. His budget reply was sound, with a $10bn housing fund. But social housing hardly begins to tackle the strategic challenge Labor faces.

The looming issue is tax policy, with its tests for both Liberal and Labor. The Liberal test is whether its big-spending agenda will eventually shatter its low-tax beliefs and see the Liberals, down the track, reverting to higher taxation in order to repair the budget bottom line.

The Labor test is now. It previously legislated the government’s stage three personal income tax cuts from 2024-25 that deliver a 30 per cent marginal tax rate for more than 90 per cent of taxpayers while preserving the progressivity of the system. While Labor has made no decision on these tax cuts, the prospect is that it will decide on an alternative tax policy model at the coming federal election to highlight product discrimination.

It is significant that in his press club speech this week Frydenberg went on the tax cut offensive. He called these tax cuts, coming at a $17bn price, an authentic reform and a future “permanent feature of the tax system”. He said if Labor was to oppose them, somebody on $80,000 a year would be $900 worse off. Highlighting their ongoing progressivity, Frydenberg said somebody on $200,000 a year, or four times the income of someone on $50,000, will still pay eight times as much tax. At a time when the budget is under attack as Labor-lite, these tax cuts stand as the shining prize of Liberal ideological continuity. They are in the law. The parliament has authorised them. Morrison and Frydenberg are all but locked in. To abandon these tax cuts under election pressure would be to trash their own brand.

Yet Deloitte Access Economics partner Chris Richardson — a strong supporter of the budget’s re-positioning — has sounded the alarm. He warned in his pre-budget Monitor that the politics of these tax cuts were probably untenable.

Richardson rebuts the progressive populists who say the tax cuts must be repudiated because they are unfair. On the contrary, he says if they are rejected the tax system will have “added complexity and worsened fairness”. But he thinks the selling job will be too hard and the benefits for higher income earners will be depicted as excessive and unfair, a position neither Morrison nor Frydenberg can afford to take.

Once again, Labor has three options. It could go to the election seeking to repeal the tax cuts, a blunder that would hand the election to the Liberals. It could neutralise the issue by supporting them — that would be courageous but risk alienating its own base. Or it could make a campaign pledge to redesign the stage three model to give middle income earners more and higher earners less.

Albanese needs to be wary. Cutting the quantum of the tax cuts, as many people advocate, would be folly. Labor’s 2019 legacy was its perception as an anti-aspirational party obsessed about imposing higher taxes on successful people and the investment class. Labor, moreover, has yet to announce its policy on negative gearing and capital gains, where it went to the 2019 election seeking a higher tax result by winding back concessions.

If Morrison and Frydenberg are given the slightest opening to exploit Labor’s tax weakness again, they will drive a truck through it. Labor needs to avoid getting caught in a variation of its 2019 mistake by inviting the critique it wants to impose a higher tax burden.

Frydenberg’s sensitivity was shown when he felt obliged to defend his document as a “Liberal budget” in the Menzies tradition. In truth, this isn’t too hard. The budget priorities are the fight against unemployment, the fight against the virus, and the fight to deliver a strong recovery. These are sound Liberal ideas. They sacrifice the fiscal repair goal — and this sacrifice is the essence of the philosophical change.

The government has acted on advice from Treasury and the Reserve Bank in this historic change of philosophy. It has a strong economic logic, at least in the short-term. The basis on which the government acted, as explained by Frydenberg, is Treasury’s projection “that nominal economic growth will exceed the nominal interest rate for at least the next decade” and, as a consequence, “economic growth will more than cover the cost of servicing our debt interest payments”.

This is part of the monetary policy revolution implemented by central banks across the globe delivering near-zero interest rates. The budget explains that this means net debt as a portion of GDP can be stabilised despite the budget itself remaining in deficit.

It is folly to attack the budget strategy while ignoring this reality, just as it is folly to assume interest rates will stay at this level forever. They won’t. The Treasury and the RBA urge the government to run expansionary fiscal policy to the stage where inflation gets its legs again and interest rates can actually shift upwards towards some degree of normality.

There is no disagreement between the Morrison government and the Albanese Opposition on the core strategy — jobs, jobs and jobs, via active government and big spending.

The goal is to drive unemployment down to 4-plus per cent, at which point wages should increase because of a tighter labour market. Labor will campaign on wages because they are the government’s vulnerability and because Labor, in addition, wants more interventions and more productivity to generate the wages pick-up sooner.

Frydenberg’s strategy is economically audacious and politically easy. The government’s achievement in the past year has been enormous and without precedent. By injecting a fiscal stimulus of $291bn, it saved the country from a feared 15 per cent unemployment level.

The Treasurer said his mission was to prevent a generation of Australians from long-term unemployment. But in a debased information age largely devoid of memory, is the public even aware of what has transpired?

New social spending is locked into the system — including aged care, the NDIS, mental health, and support for women — amounting to a new Liberal Party social contract. It will be fair-weather sailing for some time but, sooner or later, things will get ugly once spending restraint is needed to balance the books.

How long before that day arrives? Can you imagine the resentment of the community that has been fed on prolonged Keynesianism? And what political party might be in office for the day of reckoning?

The Morrison government this week fired the gun on an agenda of economic and political aggression to wedge Labor and secure its re-election, while Anthony Albanese preserved his firepower as Labor seeks to manage the greatest shift in Liberal policy for half a century.