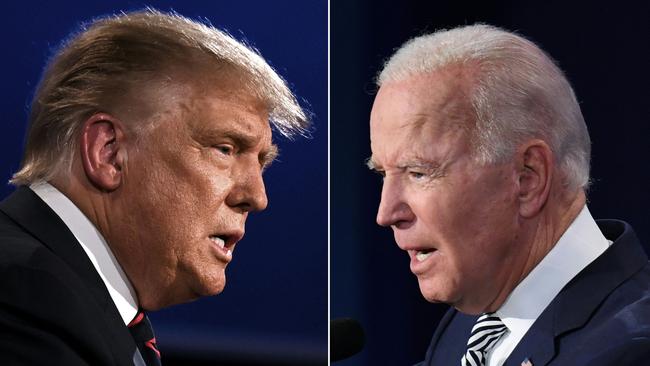

Strange but true … Donald Trump is better for us than Joe Biden

It’s a counterintuitive view widely — and secretly — held in Australian national security circles, and it is almost certainly right.

On foreign policy, despite the crazy tweets, frantic and destabilising turnover of key administration personnel, frequent bouts of boorish personal behaviour from Trump, and numerous outright mistakes, the Trump presidency has been significantly more successful than Barack Obama’s. And much better for Australia.

A Biden presidency would likely reprise Obama, but in a weaker and more woke fashion.

These judgments are provisional, on-balance judgments. Either Trump 2 or Biden 1 could go in several different ways.

The question might seem academic, given how far ahead Biden is. But don’t write Trump off quite yet. The election still depends on turnout, and Trump voters are more enthusiastic than Biden voters. The Republicans have been registering more new voters than the Democrats. RealClearPolitics still has Trump a fraction closer in key battleground states than he was to Hillary Clinton in 2016.

And consider this: at this point four years ago, the Access Hollywood tapes were disclosed revealing shocking remarks by Trump regarding his private behaviour. In reaction, there was hardly a cricket team’s worth of people in the whole of the US who thought Trump would become president.

Yet he won. That doesn’t mean he’ll win this time, but don’t count your chickens too early.

On Trump versus Biden, the arguments are strong that Biden would be more problematic for Australia. On bilateral issues, Trump has been a very good president for Australia. There is not a single issue where Canberra could have asked for much more. This reflects well on Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison, the two PMs who have dealt with Trump, and on our diplomacy. It also reflects well on Trump, and the standing Australia has within the US system. Congress and the US bureaucracy supported Australia throughout Trump’s term.

Trump honoured Obama’s deal to take asylum seekers from Manus Island, even though he hated it. He levied tariffs, including on steel and aluminium, on many nations including US allies, but not on Australia. Intelligence co-operation could not be closer. Trump went to great lengths to be a lavish host for Scott Morrison’s visit last year. Such gestures inform the US bureaucracy, and political community, about a relationship’s standing. Military co-operation has increased. Though it started off under Obama, the US marine rotations in the Northern Territory continued to grow.

OK, Trump critics would concede he has been pretty good to Australia bilaterally but has trashed US standing internationally and hurt multilateral institutions. This ultimately damages Australia’s interests. But this is not quite true, or at least there are two sides to it. Trump has done much better in Asia than in Europe. Much of what is labelled global disgust with Trump is actually European hostility, plus The New York Times and Hollywood. But a global outlook that doesn’t include Asia isn’t a global outlook at all.

The Trump administration, though it prefers deals to institutions and unilateralism to multilateralism, will build institutions, especially in Asia, where it’s useful. This week in Tokyo, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue had its second foreign ministers’ meeting. Foreign ministers of the US, Australia, India and Japan convened. This is a significant stage in the Quad’s evolution. It is the first time an Indian foreign minister has travelled overseas specifically for a Quad meeting, rather than a Quad gathering on the sidelines of a big multilateral meeting. It was important in bedding down the strategic identity of the government led by Japan’s new Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga. And it was the umpteenth visit to the region by US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, who held a long bilateral meeting with Australia’s Foreign Minister, Marise Payne, the night before the Quad.

This development of the Quad owes a great deal to the statecraft of Pompeo and US diplomacy. As ever, Asia prefers a Republican administration in Washington rather than a Democrat administration. The Republicans are the party of the Pacific, the Democrats the party of the Atlantic.

Many of Trump’s most ardent critics in Australia demonstrate the narrowly derivative and inadequate nature of their international outlook by slavishly replicating the trans-Atlantic critique of Trump, while displaying no appreciation of the Asian view.

Of course, within Asia the Chinese don’t like Trump at all. But the five Asian nations that have stood most strongly for their national interests and against Chinese hegemonic tendencies in the region — Japan, India, Vietnam, Singapore and Australia — have all had a pretty productive experience of Trump.

Asian nations are, like Trump, characteristically much more concerned with results than with process. Trump himself is concerned with what nations do more than with what they say. Australia, partly because of our increased defence effort and our straightforward political style, has achieved a unique closeness to the Trump administration — certainly much greater closeness than we ever achieved with Obama. This is most unlikely to be repeated under Biden. That is important, because we would likely have less influence with a Biden administration than we do with a Trump administration.

Southeast Asia, too, has generally found the Trump administration quite OK to deal with. It is true that Trump withdrew from the Trans Pacific Partnership, but Hillary Clinton had promised to do likewise and Obama had never submitted the TPP to Congress.

The other area where Trump has manifestly done much better than Obama is the Middle East. Trump has midwifed two new peace treaties between Israel and Arab nations. Everything Obama touched in the Middle East turned to absolute dust. Trump has been a force for stability in the Middle East, while Obama was a force for chaos — as in the fallout of the Libyan intervention and, earlier, the Arab Spring. Biden would re-adopt all the destructive elements of the old-think Obama paradigm in the Middle East, including recommitting to the plainly inadequate Iran deal.

On China, Trump has been ahead of the US political leadership class. He has been erratic at times, and has certainly made some serious missteps, but he has understood the profound ways in which Beijing flouts international norms, and the depth of the challenge it poses to the US and its allies. If these issues are now more widely understood, this is partly because of Trump’s advocacy, even as Trump has not been able to make a comprehensive and coherent case.

What about Biden?

In some ways, the future trajectory of a Biden presidency is unknowable. There are at least three separate foreign policy traditions in the Democratic Party. One is the hard-headed Democrats associated with Kurt Campbell, the former Assistant Secretary of State and author of the Obama pivot to Asia, which promised more than it delivered but was better than nothing; and Michelle Flournoy, who if we are lucky, might become Biden’s Defence Secretary.

These are muscular Democrats, particularly realistic in their views of China.

Then there are the Obama-era global engagers and multilateral institution types, associated with John Kerry, the former secretary of state; Susan Rice, who could well become Biden’s secretary of state; and Ben Rhodes, Obama’s former deputy national security adviser.

This group tends to believe that engagement itself is the objective of foreign policy. It is preoccupied with global institutions and global issues. It is deeply conventional — indeed solidly and anachronistically old-fashioned in its analyses. It suffers acute paradigm paralysis. It is drawn to the lyric poetry of foreign affairs as a kind of spiritual substitute for religion. It is perennially preoccupied with climate change and with sweeping, grandiloquent declarations on such issues. And it is very uncomfortable with, and ineffective in, the use of power.

The Chinese have learned to play this group like the strings of a harp. Thus Xi Jinping recently declared that China would be carbon neutral by 2060. This earned Beijing worldwide good publicity, but only a very few commentators stopped to ask how you could square this alleged commitment with the fact that Beijing has approved the construction of more new coal-fired power stations this year than in the past two years; that it is financing new coal-fired power stations all over the developing world; and that a vast proportion of its Belt and Road initiative projects are fossil fuel projects.

The reconciliation is actually simple. The year 2060 is science fiction territory for any government commitment. Beijing can make these announcements and not be impeded or constrained by them in any way, do just what it likes at home, and gullible Western opinion — European opinion, especially — will fall for it every time.

Biden gives every sign that he will be a dithering and weak president. He often tells friends that all politics is personal. Kamala Harris said at the vice-presidential debate that Biden told her foreign affairs is not complex, it’s just relationships.

In this, Biden betrays the same conceptual confusion as both Trump and Obama, to think that personality will seriously influence geopolitics. But it is surely London to a brick that Beijing will seduce Biden with some nonsensical falderal on climate change, and in return face significantly reduced geostrategic pressure from Washington.

The third Democratic Party foreign policy tradition is the “new left” wave of woke activism, which is where all the energy in the contemporary Democratic Party resides. That will merge with the second tradition to almost certainly make climate change the centrepiece of Biden foreign policy — a priority he has already announced anyway.

Biden and Harris are both committed to cutting US defence spending, which means probably an inferior US presence in Asia.

Taken altogether, this all likely means trouble down the track for Australia. Obama sandbagged former prime minister Tony Abbott with a viciously partisan speech at the G20 summit in Brisbane. It was the most blatant US interference in our domestic politics in decades, and it was done without notice or consideration for Washington’s Australia ally.

The hyper-partisan Democrat activists who produced that monstrosity, on fire with self righteous zeal for their pet causes, are influential in Biden’s camp today.

A second Trump administration, on the other hand, would likely be a somewhat moderated version of the past four years. Trump has much more experience now. He will still be constrained by the fear of impeachment and all the normal checks and balances of the US system, plus the normal loss of authority a president experiences in his second term.

Anchored as we are in Asia, not Europe — even less Manhattan, Hollywood or Silicon Valley — Trump Mark II would likely be better for Australia than Biden.

Strange, but true.

A Donald Trump victory would be better for Australia than a Joe Biden presidency. This counterintuitive view is widely, if semi-secretly, held in Australian national security circles, and it is almost certainly right.