Stopping the domestic violence killers

Urgent help for indigenous and migrant victims of domestic violence must be made a priority.

It has been more than 10 years since Gary Bentley heard his sister Andrea Pickett’s voice.

The last time was on Sunday, January 12, 2009. Pickett was hiding from her estranged husband, Kenneth Pickett, at her cousin’s house in Perth’s northern suburb of North Beach. She agreed on a plan with Bentley to try (again) to seek emergency accommodation the next day. But she never had the chance. Later that night Kenneth Pickett entered the North Beach house through a window. He stabbed Andrea Pickett to death on the street as she tried to flee, their three-year-old daughter in her arms.

The mother of 13 was one of 24 indigenous people killed that year by a partner or family member.

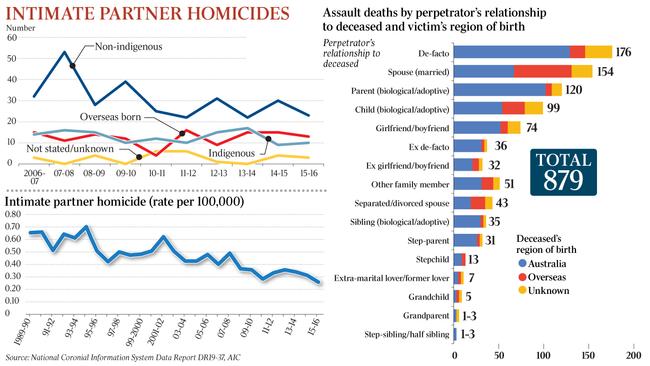

In total, 215 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were killed in the 10 years to 2015-16. Of those, 128 were killed by a current or former intimate partner, and 87 by other family members, according to Australian Institute of Criminology figures provided to The Australian.

Indigenous people accounted for 23 per cent of Australian-born intimate partner homicide victims in that 10-year period. Migrants accounted for another 22 per cent of intimate partner homicide victims (or 124 people), of those whose backgrounds were known.

The figures have prompted questions about whether programs aimed at tackling domestic abuse are properly targeted at those most in need.

Scott Morrison announced the federal government’s fourth action plan to reduce violence against women and their children in March last year, promising $328m for frontline services and prevention.

The plan included $12.1m for prevention programs for vulnerable or at-risk groups, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, as well as culturally and linguistically diverse communities. Another $35m was set aside in the plan for supporting indigenous communities.

Antoinette Braybrook, who heads a peak body for indigenous survivors of abuse, says money earmarked for indigenous people is inadequate and not “hitting the ground” where it is needed.

“There’s no funding dedicated to urban areas for our work from the federal government, and despite these statistics there has been no increase of funding to our services nationally for more than six years for our core frontline work,” she says.

The government recently announced an extra $3m over three years for the nation’s 14 family violence prevention legal services, which assist indigenous abuse survivors in rural and remote areas, but Braybrook says this is not enough.

Many in the sector are angry the government decided to strip funding from the body Braybrook heads — the National Family Violence Prevention Legal Services Forum, which helps the 14 services speak with one voice and share resources. The government subsequently restored its $244,000 in annual funding but will now distribute it to the 14 FVPLS, which will work with the government to potentially reshape the forum. Braybrook says that is “divisive”.

National action plan

Braybrook says a national action plan dedicated to reducing violence against indigenous women and children is needed.

“The statistics warrant that,” she says. “We hear our federal government talking about violence against all women as a national priority, but when it comes to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women we have got a national emergency, a national crisis on our hands.”

There is concern the $35m set aside under the national action plan is going primarily towards more policing, she says.

“If we want to make a real difference to these devastating statistics and ensure Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and children’s lives are safe and matter, we need to see an investment in Aboriginal community-controlled organisations, like our Aboriginal family violence prevention and legal services,” she says.

In the year before her murder, Andrea Pickett repeatedly had sought assistance from police and unsuccessfully sought shelter for herself and seven of her children.

Andrea and Kenneth Pickett had been married for 23 years but separated for three years. At the time of the murder, Kenneth Pickett was on parole, released two months earlier after being jailed for threatening to kill her. He is serving a life sentence for her murder, with a minimum of 20 years in jail. Four days before Andrea Pickett’s death, she told police that Kenneth Pickett had breached court orders by leaving a machete and handwritten letters at her home. Two days later he stopped her on the street with a knife and threatened to kill her. She told police she was petrified.

The coroner found multiple failings by authorities.

Gary Bentley and his sister Kelly Bentley have been fighting for changes to the domestic violence system since Andrea Pickett’s death. They say there have been some “token changes” but no real improvement to the way police and other services respond to indigenous victims of abuse.

They want changes that will help other Aboriginal women in Pickett’s position.

Her death turned the family’s world “upside down”. Kelly Bentley took in seven of Pickett’s children, who she says gave her a reason to get up every day.

In 2014, the Bentleys launched legal action, seeking financial compensation from the government and systemic changes. The case is still ongoing.

Gary Bentley says they are not motivated by money. “We just want to see change,” he says. “We want them to be held responsible for things they should’ve done and things that should’ve changed but haven’t.”

One-stop help

Chief on their list is a one-stop-shop service for Aboriginal women suffering from abuse — a service that would enable individuals to tell their story once to a counsellor who understood the way Aboriginal people communicated and “deal with things”, and then help them access all the relevant services.

Kelly Bentley also wants better training for police and more education for Aboriginal children in schools so they understand domestic violence is “not acceptable”.

On the other side of the country, the NSW regional town of Bourke once had some of the nation’s worst statistics for domestic violence.

However, since the local Aboriginal community took matters into its own hands — to seek change through “justice reinvestment” — the number of domestic violence incidents and other forms of crime has come down.

The aim is to tackle the underlying causes of crime rather than simply locking up Aboriginal people. Community representatives work together with welfare officers, legal aid, domestic violence services and others at a local hub to co-ordinate services for many of the same families.

Each morning, a “check-in meeting” is held with police, who run members of the hub through issues encountered overnight. Services are then dispatched to help families deal with problems before they escalate.

An analysis by KPMG last year found the strategy had delivered a $3.1m benefit to the community. Domestic violence-related assaults dropped 39 per cent from 2015 to 2017 and there was a 38 per cent drop in non-domestic-violence-related assaults. There were also fewer claims for Centrelink crisis payments.

Sarah Hopkins, chairwoman of Just Reinvest NSW, which has supported the Bourke initiative, says there is no magic bullet to tackling domestic violence.

The reliance on “top-down approaches” for indigenous communities is clearly not the answer, she says. Instead, Bourke shows what can be achieved through community-led initiatives.

“It’s common sense,” she says. “You need to start with the community and listen to them, look at the data, really work out the particular problems facing the particular place and craft solutions at the local level.”

During the past five years, more than 20 communities have approached her organisation to help implement similar strategies. It is now starting work with some of those, including Moree in the state’s north and Mount Druitt in Sydney’s west.

Migrant women

Similarly, those working with culturally and linguistically diverse communities believe more effort should be directed to protecting migrant women from violence.

The AIC figures reveal that 189 overseas-born people were killed by a family member in the decade to 2015-16.

Of those, 124 were killed by a current or former intimate partner, accounting for about 29 per cent of intimate partner homicides (of those whose backgrounds were known), if indigenous victims were excluded.

About 26 per cent of people in Australia are born overseas, according to analysis of the 2016 census by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Adele Murdolo, executive director of Melbourne’s Multicultural Centre for Women’s Health, says mainstream prevention programs do not necessarily reach women from migrant and refugee backgrounds. Most arrive as adults, which means they miss out on school-based programs, and they do not necessarily speak English. They may access ethnic radio stations or newspapers rather than mainstream media.

They also can face different vulnerabilities, including uncertain visa arrangements and a lack of support networks, which can make it harder for them to leave violent relationships.

“One of the reasons you need to target your efforts to migrant and refugee women is because they have different experiences to the rest of the population,” she says.

For example, she says some women face difficulties leaving a relationship because their partner may take their passport or threaten to have them deported and lose access to their children.

“If you’re going to be supporting migrant women … you really need to provide them with a tailored response that defines family violence as including that type of violence and you have to make sure the information is in their language,” she says.

Her organisation reaches some of those women by visiting factories and aged-care facilities with high concentrations of migrant women; for some, it is the first time they have received any information about family violence.

“It’s all very well to have AFL programs (aimed at stopping violence against women), but that really doesn’t reach everyone in the population,” she says. “There are lots of migrant women who wouldn’t even know when the football is on.”

Domestic homicides in the migrant community have a different profile to those in the Australian-born community, according to figures obtained by The Australian from the National Coronial Information Service.

Australian-born domestic homicide victims were most likely to be killed by a de facto or ex-de facto partner (28 per cent), followed by a parent (18 per cent). About 15 per cent were killed by a current or former spouse in the 10 years to 2016.

On the other hand, migrants were most likely to be killed by their current or former spouse (47 per cent) or their child (15 per cent). About 11 per cent of migrants were killed by a current or former de facto partner.

Homicides involving Aboriginal people also have a different profile to those in the mainstream community.

While 69 per cent of Aboriginal homicide victims were killed by an intimate partner or family member, most non-indigenous victims (53 per cent) were killed by an acquaintance or stranger (where the perpetrator and their relationship to the victim was known).

For all domestic homicides, stabbing was the most common mechanism of injury (41.2 per cent), followed by being struck or kicked (12.3 per cent) and then strangulation (11.7 per cent), according to the NCIS figures.

About 10 per cent of those killed were struck with an object of some sort and 10 per cent were shot with a weapon.

Women’s Safety NSW chief executive Hayley Foster says her body has advocated at a federal level for the government to take an “intersectional” approach to violence that recognises certain groups of women can be particularly vulnerable, including those with a disability, or who live in regional areas — who also may be indigenous or come from a migrant background.

She says funding could be better targeted towards those who are the most vulnerable.

“We are not seeing a significant enough investment,” she says.

“We’re seeing some really great projects but they’re rolled out in pilot form in some locations.

“For example, the family violence legal prevention services serve Aboriginal women and children well in some areas but the government hasn’t committed to rolling them out right around the country so that Aboriginal women and children, wherever they are, can access them.”

The Bentleys, who can still be flattened with grief when they hear one of Andrea Pickett’s favourite country and western songs even now, 10 years after her death, say it’s time for the government to act to change that.

If you or someone you know is impacted by domestic or family violence, call 1800 RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au. In an emergency, call 000. If you’re suffering from mental health issues contact: Lifeline 13 11 14; Beyond Blue 1300 22 4636; or MensLine Australia 1300 78 99 78

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout