Some moderately helpful advice for the younger generation from a boomer, ok?

And what a bittersweet task it is, for those of us who’ve waved a wistful goodbye to youth, to imagine how society might look in years to come, because our chances of participating in that society are dwindling. The fact no one else, outside a death-row cell, has any idea how or when they will die is little consolation.

Sure, there are people reading this who will set off cheerfully for work on Monday and never make it home; it may already have happened to me between the writing and publication of these words, which I have to agree would be hilarious. But vicissitudes of fate aside, for my cohort the laws of probability indicate the road ahead is considerably shorter than the one behind.

Maybe that explains our propensity to dwell on the past; it’s harder to seek a meaningful role in your truncated future than to reflect on and exaggerate your achievements, however insignificant. (At a golden oldies rugby competition a few years ago I saw a portly fellow sporting a T-shirt that read “The older I get, the faster I was”; there’s some boomer truth-telling for you.) Nevertheless, I try not to bore my juniors with burnished lies about my glory days; instead, a working life alongside waves of gifted beginners fills me with rare optimism.

Go back as far as you can in recorded history and you’ll find the same lament about how disappointing that era’s young people were: there are hieroglyphics inside Egyptian pyramids complaining of adolescent bad manners and disrespect.

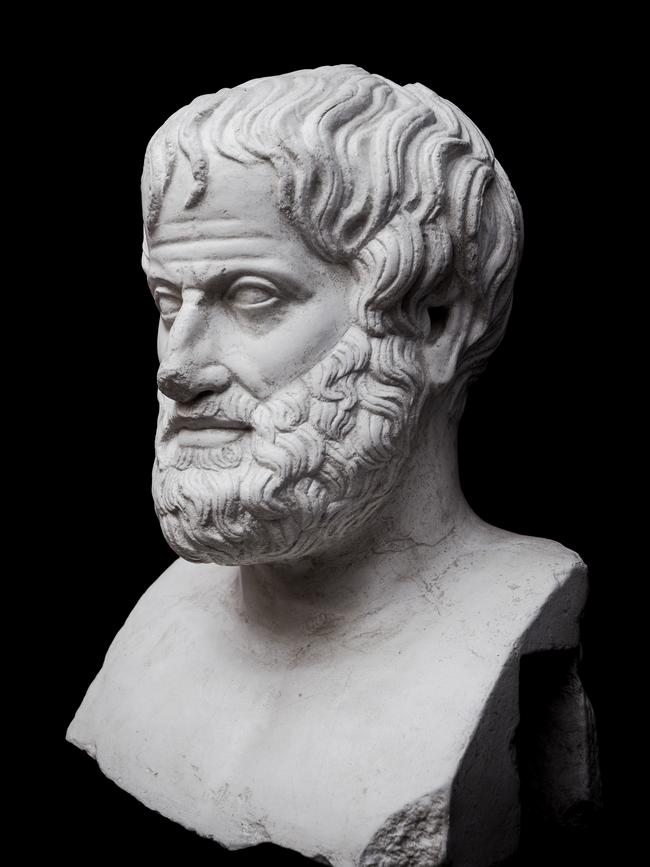

“They think they know everything, and are quite sure about it,” Greek philosopher Aristotle wrote 2500 years ago; 2250 years later, the Earl of Shaftesbury shocked Britain’s House of Commons with tales of girls who “drink, swear, fight, smoke, whistle, and care for nobody”.

The world’s population has gone from around three billion to eight billion in my lifetime. Seven billion of them are younger than me, therefore it wouldn’t seem prudent to take on a gang that size.

So, unlike many of my grumpy contemporaries, I refuse to despair of modern youth, despite their profligate whistling, and instead admire their confidence and bold wit. One of the talented young women in The Australian’s newsroom approached me recently and mentioned she’d just finished reading George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four.

“I can’t believe how bad things were for you back then,” she said, turning away with a grin before I could come up with a droll response, which I still haven’t quite formulated.

We are, happily, a fair way short of Orwell’s sunny vision, though the speed with which we close in on it appears to be accelerating; then again, everything goes quicker on life’s down escalator. But we can join George in frolicking in the gaps between what could happen, what should happen and what will.

Do we ancients have any advice worth passing on? Maybe not, but if I could urge one thing on the young, it would be to question everything: all the pieties we are expected to venerate, all those in authority, everyone who claims to have the answer. Plato records Socrates as saying, “I know that I know nothing.” Start from the principle that Socrates was smarter than our lickspittle politicians and repellent social influencers, and you’ll reduce your chances of disappointment.

As a live and delightfully contentious example, let’s consider the environment, and our attempts to manage it. There are few topics that attract such a swarm of know-alls, or consume as much of our attention and, lately, our money. I had thought the battle to cherish and protect nature, embraced by my generation, had largely been won in the Western world. (Are there many people left in Australia who throw their rubbish into the ocean?)

But laudable efforts to clean our rivers, safeguard animal habitat and scrub particulate pollution from the air seem to have been redirected to generate contagious climate hysteria, with children – and adults who should know better – trembling through their near-perfect lives, consumed with apocalyptic anxiety.

We’ve reduced an extraordinarily complex, multivariable system to one molecular pantomime villain who can be defeated, it seems, only by transferring our wealth to environmentally appalling state-owned industries in China, much of whose land and waterways are toxic sludge.

If you believe carbon dioxide is responsible for “boiling” our planet, fine; but at least note that of all the CO2 that enters the atmosphere each year, less than 4 per cent is generated by human activity. And barely a hundredth of that 4 per cent comes from Australia.

You don’t need to be a mathematical prodigy to realise that if this country sank beneath a rising ocean overnight it would have no impact whatsoever on this utterly intractable “problem”.

So even if we allow that some warming is in progress, I fear the long-term threat of climate change is dwarfed by the more immediate existential threat presented by our economically suicidal reaction to it. Just a thought, but perhaps the trillions of dollars we’ve earmarked for adjusting our climate might be better employed to mitigate whatever consequences attend on that warming.

Meanwhile, although global population continues to climb, most people are enjoying longer, safer and healthier lives. Time and again, the experts’ touted “limits” to the planet’s carrying capacity are updated, the number outpaced by our scientific advances and inventions. Remember, as you try to turn its thermostat down, the world’s a big place: at eight billion you could invite everyone on Earth to a cocktail party in Tasmania and still leave seven-eighths of the island empty.

But even as our lives continue to improve by so many measures, it sometimes feels like the opposite is happening. The dramatic advance (if that’s what it is) in communications must take a large share of the blame.

A few hundred years ago – a blink in human history – it might have been months before word of a great battle reached us. Today we know within seconds that there has been a murder on the streets of Chicago, and, despite its remoteness, we feel a little less safe.

Some catastrophic event – flood, fire or earthquake – in a foreign land used to be briefly sketched in a quarter column on the world pages of the newspaper. Now the heartbreaking stories are meticulously recounted, accompanied by numerous images of despairing survivors.

You could invite everyone on Earth to a cocktail party in Tasmania and still leave seven-eighths of the island empty

Our impotence in the face of distant tragedy is corrosive to our wellbeing, an accumulation of vicarious sorrow that can’t be exorcised by a few coins in the donation box. It’s a disturbing thought for someone who has spent his working life trying to get news to people, that they might have been better off without it.

So if I might indulge myself to address younger generations on behalf of my own, my recommendation is that you try not to be timid, aim to think for yourself and, above all, count your blessings (the old-fashioned, guilt-free version of “check your privilege”).

Marvel at the wonders that your unenlightened ancestors have heaped upon you, largely born of their mastery of reliable energy supply. Gratitude would be welcome but not mandatory.

And finally, here’s a thing I really wish I’d been told when I was young: you start out worrying what people think about you; then you grow up and try not to care what they think; but eventually you realise that they were never thinking about you in the first place. So be yourself and be brave; you probably won’t get another go at life.

In the end – a couple of world wars aside – things seldom turn out as badly as we fear. Let’s hope the coming decades are not as bleak as the hypocrites schmoozing on the slopes of Davos would have us believe. Embrace the vibe, kids, treasure and defend the precious, fragile gifts of free speech and independent thought, follow your conscience to do what’s right and, above all, good luck!

Just bear in mind that we oldsters won’t be around to tidy up after you.

It’s sobering for a member of the boomer generation – should I say proud member, as seems to be obligatory these days? Are there any humble people left in the world? – to contemplate the future, not that 2024 shoots us too far into the realm of science fiction.