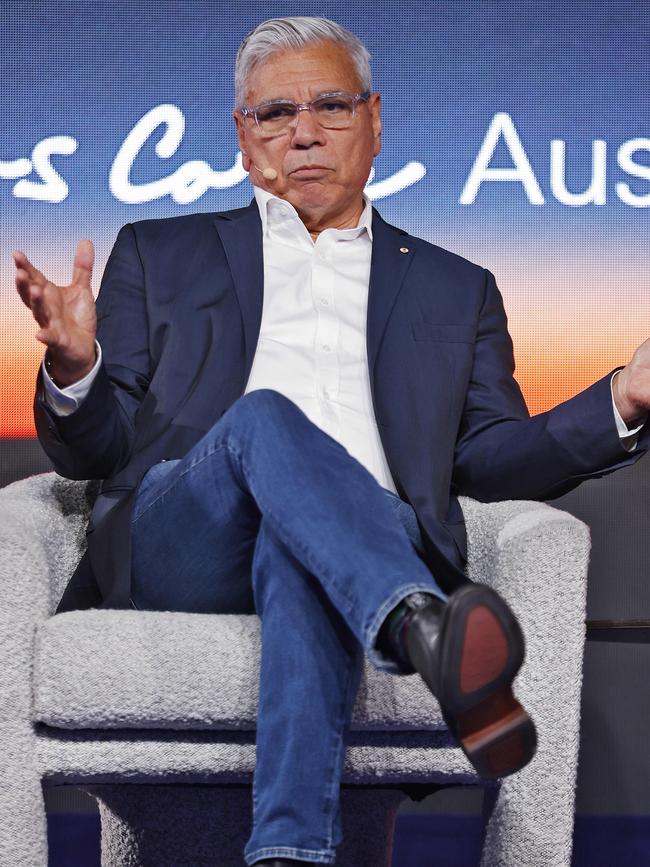

Constitutional lawyer Greg Craven asks: 'So, whose voice is it anyway?'

It is vital to understand Dreyfus is not trying to water down the voice. He is attempting to structure its operations so it will be effective into the future and pass a referendum.

The corrosive problem is the words allowing the voice to make “representations to the executive government”. Constitutional conservatives demand they be changed. The working group, composed of serious Indigenous leaders, refuses.

This issue has dominated debate over the voice for weeks. If not resolved, it will drown out the Yes case indefinitely.

The actual issue is simple. Will representations by the voice to the executive – ministers and public servants – bog down government through constant court challenges over processes or outcomes?

This worries constitutional conservatives, principally because they fear the intrusion of an activist judiciary.

But anyone concerned in government, including current ministers and public servants, must be worried. Are all their decisions to be smothered in layers of complexity and judicial interference?

There has been a distinct sleight of hand here in the development of the voice model. Originally, it was a conservative product designed precisely to avoid judicial activism.

But over the past year, groups of mainly Indigenous activists have worked to transform the model into precisely the opposite. They want a hamstrung executive. They desire High Court challenges.

The real challenge about the voice and executive action is the huge range of decisions involved. For some, you would insist on every protection. Others should be made promptly and without undue interference.

Two examples illustrate this dichotomy. The destruction of sacred sites and irreplaceable Indigenous art at Juukan Gorge was an atrocity. Preventing something similar in the future is imperative.

Whether a national voice would be effective in such a specific situation is debatable. But the principle is clear.

Then you have the decision of the Albanese government to purchase and deploy nuclear-powered submarines. In matters of fundamental national security such as this, voice representations should never base legal action.

Yet the current general terminology of “executive action” leaves the question open. Rather, the constitutional language of the referendum should give an unequivocal No.

These types of distinctions go to the heart of the Dreyfus approach to allow parliament to determine the legal effect of representations. It gives the democratically elected parliament the power to structure a principled regime.

Some decisions, such as nuclear-powered submarines, might be entirely protected against voice-based legal action. Others might operate within appropriate timelines, notice and procedures. Some would fend for themselves.

But the voice’s role would remain intact. It simply would operate, like any other constitutional or statutory authority, within a legal framework.

Media reports of the most recent meeting of the Indigenous working group – based on repeated leaks by radical pro-voice enthusiasts – show the government appreciates the legal and political difficulties around executive representations.

The fact Solicitor-General Stephen Donaghue was present testifies to the legal complexities. That Penny Wong was there, representing not only Anthony Albanese but also the government leadership in the Senate, makes the political dimension equally clear.

Which leaves the government a range of difficult choices. If it fails to win the support of the working group, it can forge ahead, relying on its Indigenous allies to eventually embrace reality. But if Indigenous leaders desert the government, how will it run a referendum opposed by its beneficiaries? Alternatively, it could swallow its political and legal concerns, and cave to Indigenous pressure groups. But then it would be pursued by the current critics of executive action, claiming the government’s own actions had demonstrated problematic drafting.

Third, the Prime Minister and the Attorney-General might defer constitutional recognition as just too hard, going with a simple legislated voice. Indigenous leaders playing constitutional chicken should beware.

So Dreyfus is trying hard to make a challenging proposal work. He should receive at least mild praise from the Yes side. But will he?

Again, there is the Indigenous working group. It was convened by Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney to advise the government on the referendum. But it is giving much more than advice.

The group, which includes some wise and wonderful Indigenous leaders and a fair helping of Indigenous career politicians, effectively asserts a veto over every aspect of the constitutional amendment. Many of its members believe the voice referendum is a matter only for Indigenous people.

They are horribly wrong. Every referendum belongs to the Australian people, who are unmoved by the diktats of unelected functionaries, Indigenous or not.

This is the basic reality for the government. It has to act in the interests of the nation as whole. It is very much in the nation’s interest to have an influential, persuasive, properly constituted Indigenous voice.

But it is not in the national interest to have a voice dictated by a few Indigenous powerbrokers insisting on an unworkable, unwinnable model. Ultimately, it is for Dreyfus and his colleagues to decide on the course forward.

At least one useful thing about the argument over executive action has been foreshadowing the tone of the Yes case in any referendum. The news is not good.

In a word, those raising queries about executive action have been vilified. They have been denigrated as racists and fools.

Speaking personally, over the past fortnight I have been publicly abused by name or clear implication as “a racist”, “culturally unsafe”, “a crybaby”, “a political fanatic”, “tribal”, “a coward”, “a liar” and a “white saviour”. I’ll live.

But others are distraught or furious to be unjustly accused. More important, the voting public will scornfully reject proponents of a referendum whose main arguments are vicious slurs. They will fear they are next.

So, as a Yes supporter, I am worried. Will my abusive colleagues be able to mount the complex Yes case required? They have mountains of corporate cash, but do they have the smarts?

In a public campaign, rather than a constitutional argument, the Yes side inevitably must marshal sentiment around five themes: past suffering; present suffering; past achievement; present achievement; and a certain jingoistic pizzazz.

It will be very easy to get the mix wrong, especially on the critical issue of suffering. I know Indigenous leaders who can keep a room spellbound by a one-minute account of their family’s plight. Others cannot.

I believe the Australian people are primed to listen to their Indigenous brothers and sisters. But a campaign based on recrimination and rejection will surely fail.

We also know something about the No side. It has its own problems.

First, it has mutated with three heads. It is the Hydra of Australian constitutional argument.

Nyunggai Warren Mundine leads the centrist group Recognise a Better Way. This group will carry much of the burden for the No case and includes high-profile figures such as former prime minister Tony Abbott and former deputy prime minister John Anderson.

Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa-Price leads a splinter campaign based on her own formidable brand, with heavy financial backing by the seriously right-wing Advance Australia.

Senator Lidia Thorpe mobilises the Blak Sovereignty movement. It has a megaphone but no financial backers or hard hitters.

These competing powers will be hard to co-ordinate without an overall statutory funding committee, as in the republic referendum. Such a committee would force ideological opposites to act in concert, just like diehard monarchists and radical direct-electionist republicans.

As a complicating factor, Mundine’s group proposes a new constitutional preamble as an alternative to the voice. But this tune is hardly catchy. First, almost no one knows what a preamble is. Second, those who do know realise it is far more encouraging to judicial activism than the voice.

Vague, aspirational preambles are the cancer of constitutions. Activist judges appropriate their sweeping expressions to pump toxins through the body politic.

Price, as presented by Advance Australia, is a compelling personality cult. Conservative admirers will defect to her from the more centrist alliance led by Mundine.

Blak Sovereignty is frankly nuts. Its revolutionary proposals could be achieved only with a bayonet.

The arguments of the two mainstream No groups have not noticeably advanced. They still proclaim racial division, an undermined parliament and a new Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission. More plausibly, they demand detail.

But if the three sets of arguments are not persuasive, they certainly are confusing, which actually may help the No case. A confused electorate rejects a referendum.

The tone of the No case is a little less abusive than the Yes side, but not much. Opponents are still idiots, traitors, naive, saboteurs and so forth. This will be a very nasty referendum.

Of course, the government retains one powerful card to play. It can sweep two powerful No arguments from the board simply by resolving the issue of executive government and providing basic architecture.

Its opponents will pray that it does not.

Greg Craven is a constitutional lawyer and a member of the government’s constitutional expert group.

The move by Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus to amend the words of the Albanese voice referendum draft is a turning point. Its rejection by the government’s own Indigenous working group would be another.