Degree of difficulty increases as PM attempts to revive Labor’s fortunes

Labor is trailing the Coalition badly on economic management, cost of living, security, immigration, and law and order, but what is worse for Albanese is that not only are they Coalition strengths – they also happen to be the areas of most public concern.

Despite the breadth and depth of all of these changes the Prime Minister has worked resolutely to maintain the impression of stability, has denied changes, refused to concede any mistakes by him or his ministers – even the ones he dumped – and sought to project an air of calm success in adhering to Labor’s plan and promises.

Curiously, all the issues are the same problems that confronted Labor in the summer parliamentary break last year that Albanese, armed with tax cuts and energy rebates, sought to bring back under control as he revived his government’s flagging fortunes.

In the winter break this year Albanese was faced again – still – with challenges over inflationary cost of living and other economic hurdles; high immigration levels and release of detainees; failure of Indigenous Australians policy and promises after the loss of the voice referendum; security fears, protests and social disruptions over Israel-Palestine; failing climate change policies and targets; construction industry corruption; airline policy on slots; and National Disability Insurance Scheme costs and reform.

But while the issues are the same, the magnitude of the challenges are much greater.

Jim Chalmers’ forecasts and promises on inflation and cost of living are faltering; there is anger over the failure of the voice referendum as Labor pivots to “practical policy”; the terror threat level has been raised with the Hamas attacks on Israel a driver of social disruption; climate change targets are drifting out; the most important industrial relations legislation is now to deregister the CFMEU; the collapse of airlines has forced changes to aviation policy; and the premiers are in revolt over federal Labor’s crucial reform of NDIS costs.

Albanese is still paying for his rash promise on the voice, early ambivalence on Israel and failing to remove incompetent ministers and admit mistakes, as well as not meeting economic promises on power prices, inflation and housing.

What’s more, Albanese doesn’t have any more tax cuts to offer as a means to ease pressure on households, and even the $3.6bn government pay rise for childcare workers announced this week will be seen as adding further to the pressure on inflation and higher interest rates.

The other problem for Albanese heading into the parliament after the break where he hopes, in Shakespeare’s words, to mark the winter of discontent and make glorious summer, is that his campaign last year to reset the government was a midterm project but he is now heading into the last parliamentary sittings for 2024 and must call an election by April next year.

Albanese continues to ridicule suggestions of an early election, on Thursday pointing to speculation of an August 31 election, which is impossible. So, too, would be a September election after the two-week sitting starting on Monday, while the King’s visit and essential protocols effectively wipe out October and November. But after August there are only five scheduled sitting weeks for the rest of the year in which Albanese can use the authority of the prime ministership and the government incumbency to shift support back to the ALP and deliver on promises to help struggling households.

Labor is trailing the Coalition badly on economic management, cost of living, security, immigration, and law and order, but what is worse for Albanese is that not only are they Coalition strengths – they also happen to be the areas of most public concern, with cost of living overshadowing all else.

This week’s Reserve Bank decision to hold interest rates at 4.35 per cent, warning that the board considered raising rates because of persistent inflation and government spending, and forecasting no return to inflation within the 2-3 per cent band before the end of next year, blows apart the Treasurer’s economic forecasts and plan.

Treasury had suggested a fall below 3 per cent by Christmas this year with the inferred hope of an interest rate cut at least before the election, which must be held by May next year. Albanese has talked of a plan to have an early budget next year after bringing inflation under control and, with it, relief to households with mortgages or paying rent. That prospect’s gone.

Chalmers also predicted that when the RBA saw the effects of his budget with cost-of-living relief such as energy rebates and tax cuts, which he argued were not inflationary but the opposite, the bank would change its outlook about inflation. That’s gone too.

The RBA’s August statement on monetary policy this week says: “The stronger outlook for public demand reflects ongoing spending and recent announcements by federal and state and territory governments. Underlying inflation is forecast to return to the target range of 2-3 per cent in late 2025 and approach the midpoint in 2026. This is a slightly slower return to target than forecast in May and is due to greater inflationary pressures in the economy. In part, this owes to a stronger outlook for domestic demand, led by higher public demand.”

On the same day the Australian Bureau of Statistics released its Living Cost Indexes, which include mortgage interest rates, showing employee households had recorded the largest annual rise in living costs of all household types, with a rise of 6.2 per cent – well above the annual inflation rate of 3.8 per cent.

One devastating paragraph and remarks from governor Michele Bullock about the RBA’s preparedness to raise rates – with the grim warning that there had to be “sustainable” reductions below 3 per cent for a cut – put the RBA and the Albanese government at odds.

In response to the RBA’s forecast rise in growth, Chalmers said it was “hard to sustain an argument that the economy is running too hot or that people have too much spare cash, given all of the data and all of the feedback that we get, which shows that’s not the case.” On Thursday Albanese backed Chalmers’ view, flatly rejecting that the RBA was pointing to government spending.

“We’re making sure that they’re getting that cost-of-living relief, but we’re doing it in a way so it’s designed to put that downward pressure on inflation at the same time,” the Prime Minister said.

Another denial and a shift of responsibility for interest rates being higher for longer. Chalmers will have to address this yawning gap between the RBA and the Albanese government’s interpretations in parliament next week.

At least Albanese’s cabinet shuffle – dumping Andrew Giles from immigration and Clare O’Neil from home affairs and putting Tony Burke in their place – will limit the obvious damage over the scandal of the release from immigration detention of convicted criminals under previous ministerial orders and the High Court’s decision last year. As a senior member of government, a former immigration minister and an aggressive parliamentary performer Burke will not be the kangaroo in the headlights Giles was. But the problems associated with immigration detainees reoffending occur outside parliament, are outside Burke’s control and bleed into the wider issues of law and order, social cohesion and security.

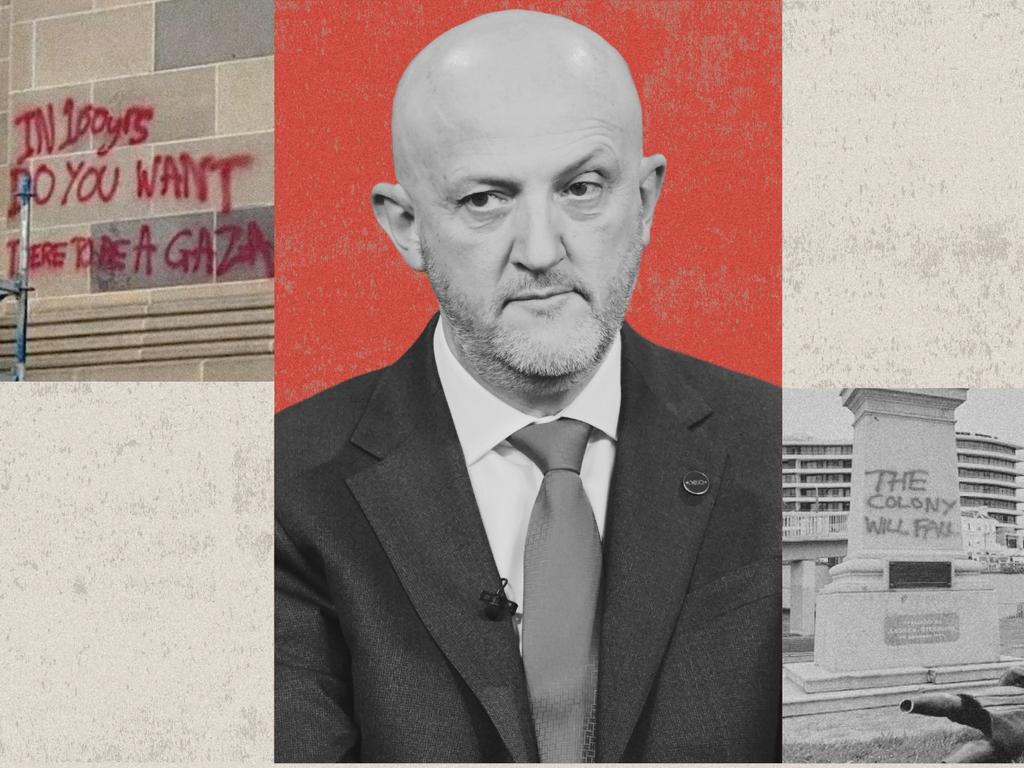

There is a dangerous public connection between social cohesion and the tensions arising from the Hamas attack on Israel and the Israel Defence Forces response that arose spectacularly this week as ASIO upgraded Australia’s terrorism alert to “probable”. With ASIO boss Mike Burgess by his side, Albanese said: “Living in a country as stable and open as ours, social cohesion cannot be taken for granted, it must be nourished and it must be cherished as a national asset.”

When asked about the Greens’ pro-Palestinian position, which will be the subject of yet another anti-Israeli motion in parliament next week, the Prime Minister, who was locked out of his electorate office for six months as other MPs’ offices were attacked, said: “It’s not appropriate for people to encourage some of the actions outside electorate offices and to dismiss them as being just part of the normal political process.”

Once again, a slow reaction to the Hamas invasion and anti-Israeli protests in Australia has led to a more dangerous atmosphere.

On his return this week from Israel and a meeting with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, the Opposition Leader set out his position with a clear determination to keep pressure on Albanese over the issue in parliament.

Perhaps the biggest echo of last summer’s reset in this winter reset was Albanese’s abandonment of the Uluru undertakings for truth-telling and Makarrata at this week’s Garma Festival. It drew angry reactions from Indigenous leaders, who accused him of breaking solemn election undertakings.

While trying to reconfigure Labor’s Indigenous Australians policy away from cultural and heritage emphases, Albanese and new Indigenous Australians Minister Malarndirri McCarthy produced a new practical approach to alleviating Indigenous disadvantage – involving renewable energy and solar farms – but again insisted there had been no change. As a senator, McCarthy will face the Coalition’s powerful Indigenous Australians spokeswoman, Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, next week. McCarthy will be an improvement on Linda Burney for Labor, but just changing personnel doesn’t necessarily solve the problem when the difficulties have become so entrenched for want of earlier action and previous failures.

In the last weeks of the long parliamentary winter break Anthony Albanese has shifted his government’s position markedly on key issues, replaced ministerial failures with more competent people, refined his attacks on his Greens adversaries and Peter Dutton, and steadfastly stayed in Australia campaigning with his colleagues and prospective Labor MPs.