It is not the first time battle has been waged over the pure white sands of Cape York.

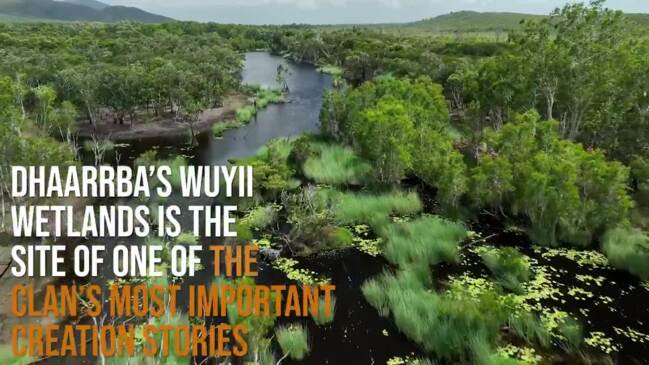

For millennia, Indigenous clans have lived among the wetlands, rainforests and towering dunes, some with freshwater lakes suspended in their windswept contours, overlooking the waters of the Great Barrier Reef.

Since Captain James Cook first made contact with locals in 1770, when the Endeavour struck coral and had to be repaired, the first inhabitants of some of Australia’s most beautiful landscape have had to fight for their survival and connection to country.

More than 150 Aboriginal people were massacred by troopers in 1881, with some of their bodies believed to remain in the dunes.

During the ensuing years, the Indigenous clans were forcibly removed and herded into church-run inland settlements or made to work on cattle properties.

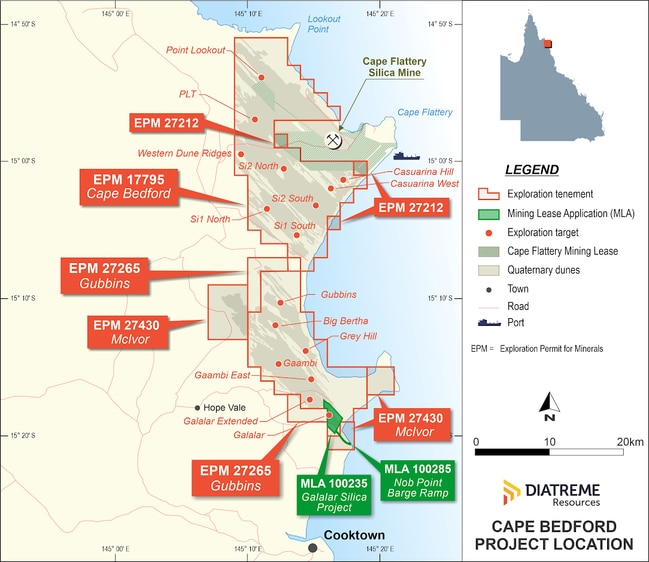

It wasn’t until the middle of last century that interest turned to the sprawling coastal aeolian dune systems – which cover more than 1000sq km in two major areas stretching up the east coast from Cape Bedford, just north of Cooktown, to Shelburne Bay, near the tip of Cape York – and its gleaming promise of riches.

The silica in the sand is among the world’s purest, and in the late 1960s the first and so far only silica mining operation – now run by Mitsubishi and touted as the world’s biggest – opened at Cape Flattery, near the midpoint of the coastline.

Its success spurred a second proposed mine 20 years later, around Shelburne Bay, which led to an alliance of conservationists and the local Wuthathi people to mount one of the biggest environmental campaigns of its time.

Labor prime minister Bob Hawke was convinced, and used Australia’s foreign investment powers to overrule the Nationals government of Joh Bjelke-Petersen and block the project.

The area around the site has since been declared national park, with much of it jointly managed by the Wuthathi. But now a new silica mine is being planned.

With an estimated mine life of 50 years, the proposed project’s exploration tenements spread across much of the dunes from Cape Flattery and extend 60km south to Cape Bedford, near the Aboriginal community of Hope Vale.

Its proponent, the ASX-listed Diatreme Resources, has touted its twin silica mines as the vanguard of the green revolution with the project’s estimated resource of 200 million tonnes of silica destined for Chinese-made solar panels.

Two other companies have exploration stakes in the same area. Diatreme is seeking Queensland and federal government approvals in the hope of beginning production in 2024.

It might help that the company has some serious political connections. Diatreme’s chairman is Wayne Swan, the ALP federal president and former deputy prime minister, and two years ago it engaged a lobbying firm, Anacta, owned by Labor campaigners who ran Annastacia Palaszczuk’s 2020 successful re-election bid and this year helped Anthony Albanese into office.

Records show Anacta contacted and met senior Palaszczuk government officials 54 times between August 2020 and July this year, on behalf of Diatreme, for reasons dubbed “commercial in confidence”.

Three of the company’s four exploration permits have been granted or extended since Anacta was employed.

Despite its size and gathering pace, the project has largely gone unnoticed outside Cape York and the individual and corporate investors buying into it. Diatreme’s pitch to government and the sharemarket has been simple and effective: the mine will ride the global transition to renewable energy and the company has “broad local support” and “the backing of traditional owners”.

In what Diatreme boasts is a national first, native title holders have been offered a 12.5 per cent “no-strings-attached” stake in the project should it get off the ground.

Swan, when his appointment as chairman was announced in November last year, said one of the reasons he had agreed to the role was the company’s “enormous foresight in its approach towards the traditional owners, giving them a direct stake in the project at an early stage”.

But it’s far from the full story.

Despite the company’s many public statements and existence of agreements with the local native title representative body, the project has split the community of Hope Vale and divided traditional owners. Many are vowing to do whatever it takes to block the proposed mine, and there are emerging questions about the validity of the purported support Diatreme received from the native title body, Hope Vale Congress, an organisation the company has repeatedly described as its “project partner”.

Earlier this year, federal regulators issued a show cause notice against Congress officials citing alleged legal breaches over its governance, financial management and removal of traditional owners – some who are among the most vocal critics of the mine – from its list of voting members.

“I suspect the directors and officers of the corporation (Congress) have improperly used their positions to gain an advantage (for) themselves or someone else,’’ the report from the Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations said in its show cause notice in April.

It also can be revealed by Inquirer that three Congress officials, including Congress chief executive and powerbroker Ivan Deemal, held 10 million shares in Diatreme, through a private company they collectively owned between 2018 and 2021.

The ORIC investigation led to the ousting of Deemal and others, with Tim McGreen and June Pearson installed as chairman and secretary respectively.

None of the allegations made by ORIC has been proven and the regulator has decided not to appoint an administrator to Congress after assurances from the new board.

McGreen tells Inquirer he wants to fix up the issues that ORIC identified and says the deals struck with Diatreme by the previous Congress board led by Deemal were not representative of the 13 clans.

“(The new Congress board) is doing business respectfully and openly,” he said.

McGreen says he told Diatreme that Congress would not negotiate until the organisation was “back on track”.

“Mining decisions will have to wait until Congress is up and running,” he says.

While cautious about talking about other clans’ land, McGreen says he’s worried about the Diatreme project’s potential impact on water.

“I’m concerned about our lifeline of water … it is our living, breathing line,” he says.

McGreen echoes other traditional owners who say they felt excluded from the mining negotiations carried out by Deemal’s Congress, only finding out about the project more than two years after the original deals were signed.

Binthi traditional owner Aaway McIvor, whose country includes the Guti sand dune within Diatreme’s exploration tenements, was one of several who formally complained to the company, Congress, and state and federal governments.

In an April 2021 letter, she warned Congress was acting more like “land developers” than trustees, and cautioned the mine posed “unacceptable impacts and threats that would be catastrophic and irreversible” to the environment, and sacred sites.

“Diatreme has no social licence to operate,” McIvor tells Inquirer. “They’re not legitimate, transparent, credible or trustworthy, and their social licence to operate should be withdrawn and withheld.”

Across Hope Vale’s clans, traditional owners including McIvor, Teneille Nuggins, Jessica McKechnie-Hart, Deleece Bowen, Lisa Humphreyson, Eileen Deemal-Hall and her mother Gwen Deemal-Hall, and others, became amateur sleuths.

Eileen Deemal-Hall says she was shocked when told of Diatreme’s plans during a clan group Zoom call in June 2020.

“We were opposed due to a lack of information, and how far negotiations and approvals seemed to have progressed without the majority of the traditional owner group knowing,” she says.

“You had whole families that didn’t know.

“There were times Lisa (Humphreyson) had to look on the ASX checking the share trades. We’d be up all night texting each other, between going to work and researching.”

Humphreyson told Inquirer: “And our main goal at the end of the day is that these people be held accountable.”

Ivan Deemal disputes suggestions Congress didn’t lead proper consultation but concedes the initial Conduct and Compensation Agreement and Cultural Heritage Assessment deals with Diatreme in 2016 and 2017 were done quickly.

Traditional owners do not have a legal right of veto over mining projects, so Deemal says he wanted to make sure they could negotiate the best royalties deal if a mine did go ahead.

“People think I’m driving this mine; but I just think I’m driving the jobs, and driving the negotiation process,” Deemal says.

“If it’s appropriately and selectively mined, it could be a prosperous thing. We don’t have agriculture here.

“We have sand, basically. We have four billion tonnes of sand, and how are we going to make money out of something that’s built on sand?

“And that’s only if the traditional owners agree to the mining. There’s a lot of processes that need to happen. A mine doesn’t happen tomorrow. It’s been five years so far.”

Diatreme estimates it could create 110 full-time equivalent jobs – including indirect employment – and become the community’s largest employer outside the council.

Deemal says it was a mistake that the 10 million Diatreme shares were bought by a private company owned by him and other Congress directors, and blames poor accounting advice.

He says they were always meant to be an investment by a charitable trust for the benefit of the community. The shares were transferred into the community trust in September last year, weeks after the ORIC investigation was launched. “As far as I’ve read the ORIC report, there’s no corruption, there are some governance issues,” Deemal says.

Another traditional owner, who asked not to be named, backs Diatreme’s job-creating potential but says it should only go ahead north of the McIvor River, close to Mitsubishi’s existing Cape Flattery mine.

Diatreme chief executive Neil McIntyre says the company’s mines would inject more than $800m into the local economy in wages, taxes and royalties, and deliver more than 100 jobs in an area of “extremely limited employment opportunities”.

McIntyre stresses that the company had to legally negotiate with Hope Vale Congress as the appointed registered native title body corporate, and insists Diatreme has “engaged consistently with traditional owners as our primary stakeholder”.

“The native title holders for the land affected by our direct activity have always been supportive of Diatreme’s activities,” McIntyre says.

Inquirer has spoken to several of those native title holders who say they vehemently oppose the company’s work.

McIntyre says Diatreme supports Congress’s decision to “pause” negotiations while it responds to ORIC’s concerns but believes that does not need to be disclosed to the ASX.

McIntyre says it is a “matter of public knowledge” that a colonial massacre occurred near the original mission site at Cape Bedford, so the area was “specifically excluded” from any Diatreme activity.

“We will never mine areas where people are known to be buried, and will continue to engage in ways that ensure matters of cultural sensitivity are accorded appropriate respect,” he says.

An environmental assessment of the dune systems was conducted by an independent scientific expert panel for a 2013 report, commissioned by the then federal government in preparation for a possible future world heritage nomination of the Cape York Peninsula. The report said the two dune areas – around Shelburne Bay and the smaller “dune field of about 400 square kilometres” between Cape Bedford and Cape Flattery where the Diatreme tenements are located – met several key themes for world heritage listing.

“Within the active dune system are hundreds of shallow freshwater lakes providing a distinctly significant environmental complex,” the report said.

“The dune fields are in a relatively natural state over much of the area and these dune fields are outstanding and rare examples of tropical dune systems, with geological/geomorphological conservation values of international significance and occur on a scale unusually large for the humid tropics generally.”

One of the report’s authors, Peter Valentine, an adjunct professor at James Cook University, says he is concerned by the spread of the proposed mine’s explorations permits.

“It is a complex interdunal system and you need a big area protected, not a little park, for it to operate as it should,” he says.

Renowned ecologist Peter Stanton, whose field work on Cape York over more than 30 years was instrumental in the declaration of protected areas including the Daintree and Cape Tribulation, says the push for climate-friendly solar power could come at the expense of the local environment.

Stanton says the vegetation and lakes would be at risk with the mining of the dunes.

“The lakes are particularly vulnerable, they are suspended within crusts of the dunes and can be easily fractured,’’ he says.

“It could lead to massive environmental destruction or vandalism of this landscape which is being done in the name of developing green energy.’’

More Coverage

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout