We should never have signed up to the train wreck that is the ICC

Even 20 years ago, one needed only delve into the putrid state of other international forums to understand the ICC would go off the rails, as it did this week. The only surprise is it has taken so long for more people to realise this.

After the first tranche of 66 states signed up to the court, an Israeli-Arab politician suggested the Israeli prime minister and his cabinet should immediately be investigated for war crimes.

Even back then, one needed only delve into the putrid state of other international forums to understand the ICC would go off the rails, as it did this week. The only surprise is it has taken so long for more people to realise this.

As a public critic of the Howard government signing Australia up to the Rome Statute that established the ICC, I take no pleasure in being right. Well, maybe a teensy bit of I-told-you-so satisfaction.

The moral relativism and politics behind ICC prosecutor Karim Khan’s decision to seek arrest warrants for “war crimes” against Israel’s leaders, Benjamin Netanyahu and Yoav Gallant, along with three leaders of the terrorist organisation Hamas, ought to be the final wake-up call to every sound government that grand mistakes like signing up to the ICC are hard to unpick, at least not before a great deal of damage has been done.

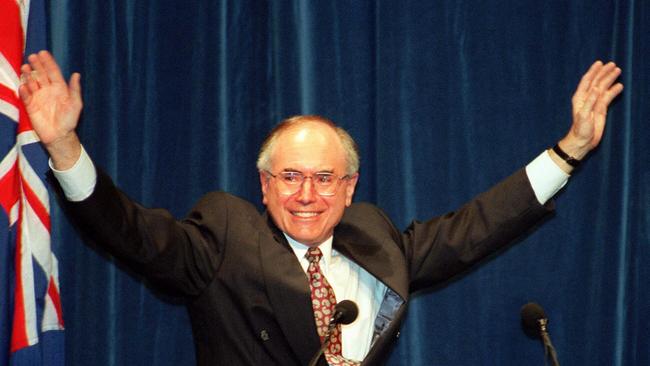

It never made sense for prime minister John Howard and foreign minister Alexander Downer to subject this country to an untested and permanent international court. Sure, misguided souls on the left of Labor might do it, even today. Penny Wong would be a shoo-in to fall for the guff that only good can come from this international “legal” body. Anthony Albanese, the nation’s follower-in-chief, would do what he is told by his more powerful ministers.

But Howard and Downer? Few have been such powerful defenders of national sovereignty. In government, they scoffed at international elites from various UN bodies that tried to meddle in our immigration policies. They snubbed supranational elites trying to meddle in our domestic Indigenous policies.

The Howard government’s vision was clear: self-governing democracies are the best protection from government abuses. The ability to boot out politicians tends to focus their minds on the importance of treating people right.

Why then did Howard and Downer fall for promises that this untested international court would stay above politics? Speaking to Inquirer this week, Downer put it down to a “burst of idealism”.

Following that admission, he didn’t mince his words: Khan had “single-handedly destroyed the ICC” and “liberal democracies won’t take it seriously” any more.

Downer said the sad thing was that “this is part of a trend which is the gradual destruction by the left of these multilateral institutions”.

He is right about one thing – his burst of idealism. His other claims are, even more sadly, wrong. The ICC hasn’t been destroyed by a wanton dive into politics. The whole purpose of international law is politics by another means. That’s why signing on to this body never made sense from someone as attuned to the agenda of the international elites.

Downer said this week that if the panel of ICC judges granted arrest warrants for the Israeli Prime Minister and Defence Minister, “I would withdraw all together from the (ICC) statute”.

It has been done before. US president George W. Bush unsigned the Rome Statute in 2002 (after Bill Clinton’s wayward decision to sign it despite recognising “significant flaws”).

Of course, the globalists unleashed the usual loathing for democracy. “Signature removal is unprecedented in American international legal practice,” said one law professor. It would “signal to the world that democracies can unilaterally sign or unsign treaties whenever there is a change of government”.

Well, yes. That’s the point of a democracy. National sovereignty is in serious trouble if democracies cannot “unsign” treaties. The world needs more, not fewer, signature removals if internationalists are to understand this thing called democracy.

Howard told Inquirer this week he and Downer were convinced the safeguards contained in the Rome Statute would protect democratic countries such as Australia – the main safeguard being that the ICC would not meddle in a country’s affairs unless its own judicial system refused or was incapable of prosecuting war crimes.

That promise didn’t help the only liberal democracy in the Middle East, as we have seen this week. Which is why Israel refused to become a member of the ICC. Why were Howard and Downer so naive?

When has any international body remained above politics? When countries were being asked to sign on to the ICC, the warning signs were loud and clear.

Barely a year before the ICC opened its doors for business, the UN won the 2001 Nobel Peace Prize for its work for “a better organised and more peaceful world”.

Was this a parody? A month before winning that prestigious prize, the UN hosted what can only be described as the most disorganised and wickedly divisive UN conference ever. The Durban Conference Against Racism, Racial Intolerance, Xenophobia and/or Related Intolerance served to inflame large doses of racism, racial intolerance, xenophobia and/or related intolerance – against the Jews and the West.

The gabfest in Durban was about pointing the finger at the West for the world’s growing list of woes. Its underlying premise, in common with most other international forums, is that the Third World was born guileless and innocent, only to be brutalised by the West. It’s an especially popular theme with self-hating activists in the West.

As delegates dispersed from Durban, they were left with the resounding message that slavery was slavery only when carried out by the West. And racism is racism only when whites discriminate against blacks, or when Christians or Jews discriminate against Muslims. Never mind that racism and religious intolerance is rampant in countries such as Saudi Arabia, India and Malaysia.

As one pundit said not long after, “How can the world expect Israel to trust the UN or any organ created by it after that debacle?”

That was around the same time the French ambassador to Britain referred to Israel as “that shitty little country” in an off-the-cuff remark. The animosity Israel faced back then from the so-called international community – meaning Europe and the Arab world – was palpable. When countries – including Australia – signed on to the ICC, it must have been seen by many internationalists as a licence for feral anti-Israel animosity.

It’s one thing to hold a gabfest slamming the evil West. It’s another thing when international prosecutors use the armoury of the ICC to advance their political agendas – how else to explain the moral equivalence shown by Khan when he packaged up Israel’s political leaders with Hamas terrorist leaders?

Howard told Inquirer he did not wish to “relitigate” his government’s decision to sign Australia up to the ICC. Fair enough. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to learn something from the Howard government’s mistake.

The one big difference between national and international politics is that a national electorate can deliver wake-up calls on a regular basis at democratic elections. Delivering that same message at the supranational level is much harder. There are no elections. That’s why globalists get away with so much. It’s why activists with a law degree often choose international law as their playground. Amal Clooney, who along with other British lawyers reportedly advised Khan about this latest ICC move, is their poster girl.

While it’s essentially the execution of politics by another means, modern international law also offers the extra thrill of religious zeal. Witness the overt moral authoritarianism that expects people even in liberal democracies to cede power to a higher authority.

Former New Zealand politician Max Bradford described it best. “The closer to God you are, the greater the moral authority you have to impose your view of the world on those below you,” he said many years ago. “As international organisations are perceived to be closer to God than member states, the greater is the moral authority they can wield.”

At the pinnacle of international law, the ICC sits closer to God than any other international body.

That’s a hard line to swallow for pagans like me who believe voters should make the laws. And when pagans challenge the religion of international law, we are reviled for not believing in “human rights”. In fact, it’s the globalists who have little time for “human rights” – real human rights, like the democratic right to vote.

That’s why Australia’s decision to sign up to the ICC was so vexing. The whole point of supranational institutions is to lift policy, decision-making and judgments above national parliaments – to do what the Americans call an end run around democracy.

Indeed, the most dangerous part of the international law movement is that by hijacking the legal system and turning it into a political forum, activists acquire immunity from any of the accountability measures that restrain the conduct of politicians in democracies.

True legal systems do indeed need to be free from political interference if they are to oversee politicians. This means the key components of institutional legal systems must have fixed tenure, independently set remuneration and be immune from the buffeting of elections and electoral cycles.

The quid pro quo for this independence is that judges must stick scrupulously to the law and avoid political judgments. The same is true of prosecutors – politics must not infect their decisions. This fundamental compact is broken when international legal institutions become politics by another means.

This week, Anthony Albanese and his ministers backed the ICC, saying they respect international law and the ICC’s independence. Either they are missing the point or they are part of the hoax that the ICC is a legal institution. The worst feature of the ICC and similar transnational courts is not that they are populated by clowns but that unelected clowns are making political decisions.

If you can use legal systems to make political decisions, you can make those decisions permanent, and beyond review. Never mind that judges are poorly equipped to make such judgments – their belief in their own wisdom is frequently matched only by their ignorance of policy.

Alas, the march of activist lawyers into quasi legal-political decisions advances daily, from the heavens of international legal bodies such as the ICC right down to your local bar association or law society promulgating some activist rule to which its members are forced to adhere. The aim is to leverage these administrative rules into codes of conduct, then into legislation and then into judge-made law that is even more permanent than legislation. No wonder today’s young Marxist law students aspire to run their local Bar council as a first step towards remaking society.

When I called Downer on Tuesday morning, before there was even a hi-how-are-you, he said: “I know why you’re ringing me. You want me to say you were right and I was wrong.”

That wasn’t the purpose of the call. The reason was to understand how an otherwise formidable foreign minister got it wrong. Perhaps current and future politicians might find his insights instructive. Downer spoke to me from California where he is a distinguished visiting fellow at the Hoover Institute at Stanford University. Before our call ended, he admitted he was wrong to ratify the treaty that set up the ICC. It takes a big person to admit mistakes.

More than 20 years ago, I warned in columns and public speeches that the International Criminal Court would become a court of men, not laws; a court of politics, not principles. It was clear on the first day the ICC became a reality.