Sharia spread by stealth across Indonesia

Women and minorities are on the wrong end of religion-inspired discriminatory bylaws spreading across Indonesia.

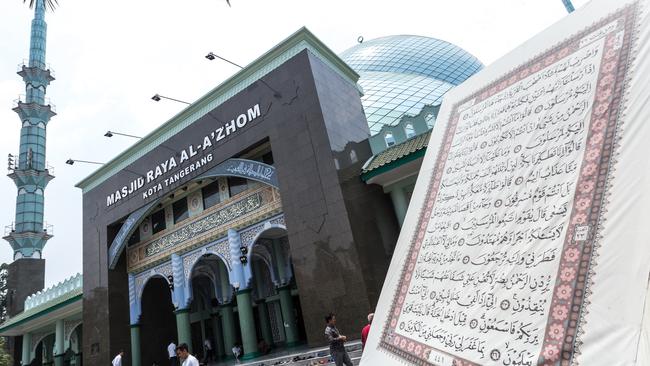

Ani Anugrah* was working a late shift at a relative’s roadside truck stop in Tangerang — a satellite city just south of Jakarta that hosts the Indonesian capital’s international airport, an Ikea store and several large corporate headquarters — when it was raided by local “public order” enforcers on suspicion of immoral activity.

Ani was out back washing dishes when the raid occurred but was taken for questioning and held in a cell overnight after failing to satisfy officials that she was not a prostitute.

“Nobody came to bail me out. Actually I was ashamed to trouble anyone (because) everyone already makes a big deal of my status as a widow,” she said of her 2016 arrest, which left her feeling stigmatised and scared.

Prostitution is not a crime in Indonesia, but in Tangerang and many other districts and municipalities across the country it is banned under local bylaws that increasingly have been used to impose strict morality codes — often referred to as sharia-style regulations — on local populations.

Islamic dress codes, including mandatory or strongly recommended hijabs for female civil servants and schoolgirls, and bans on alcohol and prostitution (which impose de facto night-time curfews on women) are among the most common of these morality provisions.

They also can include enforced religious practices such as mandating a standard of Koranic knowledge for Muslim students to matriculate and for Muslim couples before they may marry, and obligatory closure of food stalls during Ramadan fasting hours.

Two years ago, another Jakarta satellite city, Depok, even formally enshrined gender roles in family life and the circumstances under which a woman might become head of a family and go out to work — divorce, the death of a husband or in cases where he does not fulfil his responsibilities as outlined in the city’s Family Resilience bylaw.

Aceh is the only Indonesian province to formally adopt sharia, as part of a controversial peace agreement aimed at ending its 30-year-long separatist struggle.

Violators of its strict Islamic criminal code are publicly whipped outside mosques each Friday by hooded punishers for crimes ranging from gambling to drinking, public affection between unmarried couples, and consensual homosexual sex, even as the rest of the country is governed by civilian law.

Yet across Indonesia, provincial, local and district governments have been steadily encroaching deeper into personal lives and freedoms through the imposition of discriminatory bylaws on their populations.

In Tangerang those forced to break the de facto curfew imposed by anti-prostitution laws — very often poor women like Ani working low-wage, nightshift jobs — risk being swept up in raids by public order officials hoping to catch out offenders.

But they are not the only ones.

Human Rights Watch says in recent years there has been a notable crackdown on the LGBT community, and new bylaws criminalising activity that is seen to “promote a gay lifestyle”.

“That can mean anything from sounding ‘sissy’, to holding transgender meetings in a public place or holding a private gay party. All can be criminalised,” HRW Indonesia spokesman Andreas Harsono says.

Many local religion-influenced bylaws contradict rights enshrined in the Indonesian constitution, a document drafted more than 70 years ago by politicians who considered, then opted against, wording that would have obliged Indonesian Muslims to follow sharia. But with religion seeping deeper into Indonesian political life, politicians at every level are feeling the pressure to prove their Islamic credentials.

Michael Buehler, a senior politics lecturer at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, says Indonesia now has 770 discriminatory or “sharia” bylaws — a sharp rise on the 443 bylaws introduced between 1998 and 2013. While the laws are heavily concentrated in areas with strong Islamist movements — East and West Java, Banten, West Kalimantan, West Sumatra, Aceh and South Sulawesi — many were passed by politicians from secular parties such as President Joko Widodo’s Democratic Party of Struggle and Golkar, in exchange for electoral support. But Buehler says sharia bylaws, particularly those relating to religious taxes and alms, have more recently “spilled over into other provinces”.

Khariroh Ali, a commissioner with the country’s National Commission on Violence Against Women (Komnas Perempuan), says the rush to police Indonesians’ private lives and religious adherence is being propelled by a “moral panic” whipped up by Islamist politicians at a local and national level.

After years of debate, Indonesia’s outgoing national parliament last month tried to push through sweeping changes to the colonial-era penal code that many feared would wind back hard-fought democratic freedoms and personal liberties. Coupled with mass outrage over new laws that weaken the country’s powerful Corruption Eradication Commission, the move sparked the biggest nationwide student protests since 1998 when mass demonstrations brought down the Suharto regime.

Joko, also known as Jokowi, was forced to intervene and ask the house to refer the bill to the new parliament, which was sworn in this month. But there is little difference between the new and old parliament and no suggestion there will be pushback against the draft bill when it is once again tabled for enactment.

Among the most media-scrutinised of the proposed penal code revisions was the imposition of jail terms for those found guilty of sex or cohabitating out of wedlock. The notion that young Australian visitors to Bali might face jail time for premarital sex whipped up a frenzy of concern and even prompted the Australian government to issue a pre-emptive travel advisory.

But Khariroh says an even more pernicious article in the code is one that would legitimise and enforce so-called “living law”, a catch-all term that covers sharia bylaws but also a growing number of local government “circulars” issued as a means to enforce morality laws without subjecting them to legislative debate. “This ‘living law’ clause is one of the biggest issues for women because it will exacerbate discriminatory practices that already happen in society,” she told Inquirer.

“Customary law rarely favours women, so if this kind of living law is accommodated in the new penal code then we will see these discriminatory practices become a tool to prosecute women.”

For years Komnas Perempuan has documented and advocated for women who have fallen foul of discriminatory bylaws. But the commission’s efforts, and those of the Indonesian government, to challenge the laws were dealt a blow in late 2017 when the Constitutional Court ruled the Home Affairs Ministry did not have the power to overrule them.

Khariroh now heads a government taskforce — which includes staff from the Ministries of Women’s Empowerment, Justice and Home Affairs — charged with setting anti-discrimination guidelines for local governments.

“But until now we haven’t even been able to agree on what is discriminatory to women and what isn’t,” she told Inquirer in exasperation, illustrating internal government conflict over the laws. “We are still struggling to come up with those definitions.”

Just how challenging Indonesia’s political landscape has become for those pushing a progressive agenda was illustrated earlier this year when Grace Natalie, the Christian, ethnic-Chinese leader of the new Indonesian Solidarity Party (PSI), faced a blasphemy investigation over her party’s vocal opposition to religion-inspired bylaws.

The youth-based secular party went to last April’s national elections with a suite of progressive policies including the elimination of all discriminatory religion-based bylaws, support for an anti-sexual violence bill and reform of the blasphemy laws.

But their policies left them open to attack by the same Islamist forces that in 2017 unseated former Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja “Ahok” Purnama, another ethnic-Chinese, Christian-minority politician, and campaigned successfully for his blasphemy prosecution and jailing.

PSI legal spokesman Rian Ernest says the orchestrated attacks on party leaders coupled with the party’s disappointing election performance — it failed to secure the minimum 4 per cent of the vote needed to secure seats in the national parliament — has forced them to “tone down” their message.

“Speaking out against sharia bylaws and the intersection of religion and politics in this country is a delicate issue because, regardless of our intention and how carefully we speak, our words can be twisted,” he told Inquirer. “That’s the lesson we learned from the election. It won’t hinder us from dealing with these topics but maybe we will have to be more careful.”

There is also the matter of public opinion. While the laws clearly worry many Indonesian religious, sexual and gender minorities, a survey last year by the respected Indonesian Institute of Sciences suggests they have broad appeal within provincial Muslim communities.

More than half the respondents said they agreed with sharia-style laws at a local level, even if many of the same people supported Indonesia’s foundational Pancasila doctrine — democracy, social justice, humanity, unity in diversity — at a national level.

And the PSI isn’t the only one calibrating its message. Even as discriminatory bylaws are growing and spreading, the number of voices prepared to speak out against them has dwindled. Two previously outspoken critics refused to speak to Inquirer for this article while another dismissed it as an old issue.

“It was an issue five or 10 years ago. Now it is just ink on paper,” Ulil Abshar Abdalla, from Indonesia’s Liberal Islamic Institute, told The Australian in an online exchange. “Nobody cares about sharia bylaws in provinces any more.”

That the implementation of Indonesia’s so-called sharia bylaws is patchy is undisputed but it doesn’t make them any less dangerous, insists Ismail Hasani, from Jakarta’s Setara Institute for Democracy and Peace, who points out that once they have been passed they are nearly impossible to revoke.

“In my experience, these laws are still upheld even if just to show dominance, to scare the public. These bylaws violate human rights and they are spreading from one region to another … and the central government hasn’t spoken up about this,” he told Inquirer. “We are already seeing an effect at the national level through the proposed criminal code. There are definitely traces of sharia law in the criminal code draft, which is promoted by both secular parties and Islamic parties.”

He fears a broader push to “formalise sharia law in Indonesia by incorporating Islamic values” into the country’s legal system. While the bylaws “clearly reflect the Islamists’ war against women and their autonomy”, he says, they have a far wider impact.

Across Indonesia, more hotels are seeking sharia accreditation and imposing morality regulations on guests including a ban on alcohol, all “LGBT activity”, and a requirement that all couples produce a marriage certificate.

Fastrooms Hotel in Bekasi, on Jakarta’s eastern fringe, declared itself a sharia hotel in February, pasting notices on the walls of its rooms advising of its new rules “in accordance with the concept of Islamic sharia”. Since then, a hotel spokesman says, it has seen a rise in family business because people feel safer “knowing we don’t let any wrong people in here”.

Four months ago, Tangerang City’s public hospital became the first government clinic in Indonesia outside of Aceh to become sharia-certified. Under new guidelines, all food and medicines must be halal-certified where possible, and patients treated by doctors and nurses of the same sex unless a male “mahram” (relative) is available for female patients — who are also encouraged to wear hijabs.

The Muslim call to prayer is broadcast five times a day, medical staff are asked to pray before operations and procedures, all female patients are provided with modesty curtains that they are advised to draw whenever a male enters the ward, and terminal patients are given final prayers.

On the walls of each hospital ward are reminders that “wearing a hijab and covering the aurat is a way to make patients comfortable”. Stickers outside bathrooms also remind patients to recite a Muslim prayer before and after abluting. Hospital director Henny Herlina says sharia principles embraced by the hospital are “universal values”, and that “even non-Muslims will be more comfortable if their privacy is taken care of”.

“People think because it is a sharia hospital it only accepts Muslims and forces them to dress a certain way. That is encouraged, but we don’t enforce it,” she told Inquirer. “There is no contradiction between us serving the patients and us following sharia principles. It doesn’t get in the way of us serving the people. In fact it may make our service better.”

Additional reporting: Chandni Vasandani

*Not her real name