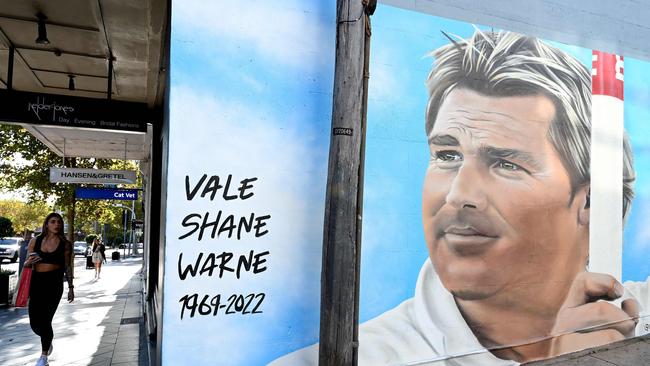

Shane Warne: the final farewell

Australians have a long history of honouring our heroes taken from us too soon.

A few days after the death of Shane Warne, we walked to the Melbourne Cricket Ground to see the tributes placed beside his statue. Prominent were bunches of flowers, placed alongside many full cans and bottles in the green and red colours of Victoria Bitter, as well as a box full of beer cans, four tins of baked beans and a small jar of Vegemite – a fascinating insight into Warnie’s reputed diet.

Visible, too, were grief cards in envelopes, and a large sheet of white paper, presumably written on by a small boy declaring that he, too, hoped to be a bowler: his spelling of that word was a brave attempt. A cricket official arrived while we, the small and silent crowd, stood around, and he gathered the letters and grief cards so that, as he informed us, the Warne family could read them.

How had our nation’s folk heroes in earlier years been honoured? Perhaps the first large-scale funeral or memorial service was held in 1863 when the bones of the explorers Burke and Wills – carried all the way from central Australia – were buried in Melbourne. The coffin, enthroned on a lofty hearse drawn by horses, crowned the long procession of people that set out from the new Parliament House and proceeded down the long stretch of Bourke St, its shops draped in black cloth, before turning north. The spectators lined the funeral’s route all the way to the Carlton cemetery and took off their hats as the coffin passed.

As Sydney and Melbourne grew into large cities, the funerals of sportsmen drew big crowds. It is not surprising: Australia was probably the first country to become enamoured with spectator sport. Here were probably the world’s first cities where a notable section of the workforce was granted a half holiday on Saturday, thus enabling crowds to attend sporting events. Of course, Sunday sports were still forbidden.

Who now has heard of 23-year-old “Harry” Searle and his street-packed funeral in two Australian cities? Henry Searle was the world’s most famous professional sculler during those few decades when individual rowing was one of the three or four major spectator sports in English-speaking lands. Born near Maclean in the Grafton district of northern NSW, where most of the wide coastal rivers were not yet crossed by bridges, he competed with the muscular young men who earned their living by rowing children to and from school, and carrying rural produce to the nearest general store or steamship wharf.

Searle won the world championship on the Thames near London, receiving the prize of £1000 after a one-sided race against the Canadian champion William O’Connor, but he caught typhoid while returning home and died in quarantine near Melbourne in December 1889.

Beginning with a procession along crowded Melbourne streets and followed by the Anglican burial service read aloud at Spencer St railway station, his coffin also attracted thousands of his barrackers at the NSW stations where the funeral train briefly stopped. On a hot day in Sydney, his funeral moved so slowly along almost-silenced city streets – the onlookers were crammed and a few “narrowly escaped serious injury” – that it did not reach the doors of St Andrews Cathedral until about 5pm. By the time his coffin was reverently carried onto a small steamship for his final voyage up the coast, the crowd watching the funeral that day was estimated to have numbered about 170,000. If true that would have equalled half of Sydney’s population in 1889. Finally, Searle was buried at the small river port of Maclean which, this month, was almost submerged by the floods.

Is Warne in his heyday as famous as Searle was in his year of triumph and death? Warne undoubtedly is. Here, cricket was and is a nationwide sport whereas professional sculling – now moribund – was mainly centred on NSW. Moreover, cricket today is a favourite game in nations holding more than one quarter of the world’s population, and therefore Warne and his spin-bowling have been seen by many hundreds of millions of people at one time or another.

But we must not detract from Searle’s high fame, even though it was short-lived. In the era before World War I, no single day of a cricket match anywhere in the world attracted as many spectators as thronged riverside London just to watch Searle and his rival rower, far behind, come into sight.

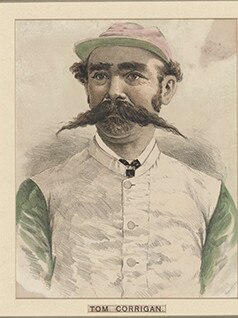

Victoria’s biggest funeral in the same era was that of the jockey Tommy Corrigan. Born in County Meath, Ireland, he came here as a teenager and soon became a champion over the jumps, which was then a tremendously popular form of racing.

His tally of 235 victories included seven cups from the Grand National Steeplechase.

Very small in physique, Corrigan was genial in disposition, honourable in his racing tactics, and loyal to his Catholic Church. At the Warrnambool historical society is a memorial plaque depicting Corrigan and his celebrated handlebar moustache that – neatly waxed – extended far beyond each cheek. Did he really race with such an encumbrance on his face?

Corrigan, by now in his early 40s, fell heavily during a steeplechase at Caulfield racecourse in August 1894. Dying two days later from brain damage, he left behind two small children, and that fact was said to increase the crowd of sympathisers when his funeral made its slow journey towards the distant Carlton cemetery.

Led by a regiment of jockeys and trainers on foot, with the lid of the coffin itself displaying Corrigan’s riding boots and green and white jacket, the procession extended 3km along St Kilda Road. At Swanston Street, which was shut to other traffic for several hours, “one great mass of humanity” stood waiting patiently on that winter’s afternoon. Melbourne had not previously seen such a huge gathering.

Warne in his homeland was more celebrated than Corrigan, who was essentially a Victorian. In the realm of cricket, a comparison of Warne with Sir Donald Bradman is more complicated. Though Warne’s name is the more familiar to cricket enthusiasts in Asia, it is probably not quite as famous in Australia and England as was that of Bradman in his faraway heyday. If Bradman in the late 1930s had, like the sculler Searle, caught a fatal infection on a homeward voyage, his funeral in Adelaide would have been enormous, and the press coverage in London almost endless. Bradman, however, lived on for more than 60 years.

How apt that Bradman’s grand daughter Greta should sing the national anthem at the forthcoming grand tribute to Warne.

In Australia, the greatest funeral honouring a woman was for Dame Nellie Melba, who in the era of the gramophone was the most brilliant soprano in the world. She died, aged almost 70, in Sydney in February 1931.

The train carrying her body towards her birthplace, Melbourne, often had to slow down so that admirers clustered at the rural level crossings, and the neat rows of bare-headed schoolchildren standing at small-town stations, could pay their respects. At Albury, a brass band was waiting to play the hymn Abide with Me.

When, in Melbourne, her funeral departed from Scots Church – the ornate cathedral built by her father – the crowds in the street were immense. Along the road to what was then the country town of Lilydale, hundreds of groups of spectators were waiting long before the approach of the hearse and the five motor-vans packed with wreaths. According to Ann Blainey’s biography, I am Melba, it was almost evening when the funeral, now headed by a local troop called Melba’s Own boy scouts, reached the cemetery.

By 1950, the era of the “big-crowd funeral” was almost over. It reflected a world which was more sympathetic to religion and was poorer, materially, than we are today. In that era at least half the people could not afford to pay even a few pence weekly for entertainment; but here were pageantry and drama and funereal music passing along the street and free of charge, with the prime standing room open to the poorest family if it arrived first. But now the cinema, radio and soon television enabled people sitting at home to watch in comfort a celebrity’s funeral.

Perhaps the last of the huge funeral processions honoured General Sir John Monash in Melbourne in October 1931, just eight months after Melba’s death. Commencing at Parliament House and ending with Jewish rites performed at the distant Brighton cemetery, Monash’s procession attracted a crowd estimated by historian Geoffrey Serle as “probably the largest in Australia to that time”. On that afternoon the 250,000 people said to be standing and waiting during that long afternoon were paying respect and gratitude primarily to their nation’s most eminent soldier, a hero of the last dramatic months of the First World War, but also to all their own relatives and friends who during that war had died on foreign soils or seas, and had been interred with none of their family present.

Sportsmen, especially if they died before their time, were more likely than politicians to receive a big-crowd funeral. A politician who died in middle age was unlikely yet to have acquired fame. In the era before television, even the funerals of such distinguished prime ministers as Alfred Deakin, Billy Hughes, John Curtin and Ben Chifley, all of whom passed the age of 60 before they died, did not draw large crowds, for their admirers were scattered across the nation rather than predominant in one city.

One of the noteworthy politician funerals was not in a capital city but in Broken Hill. Percy Brookfield, a miners’ leader who was too radical to remain in mainstream Labor, was a member of the NSW parliament when, on a country railway station, he was fatally shot after bravely tackling a mad passenger armed with a revolver.

His funeral in Broken Hill on Good Friday 1921 was a stirring event, and the tall monument above his grave still preaches the message, “Workers of the World Unite”.

The public tributes to Warne and the ticket-only ceremony at the Melbourne Cricket Ground on March 30 emphasise how much the spectator sports retain their magnetic quality. A mix of political and social factors determine the fame of sports stars.

Often a premature death is one factor, and the personality of the star is another. Warne had the gift of gaining affection from, and giving it to, a wide range of people, as Peter Lalor and Gideon Haigh and The Australian’s other cricket correspondents have faithfully reported.

Was Warne the embodiment of the old Australian larrikin? Yes, he was, but he was also the dashing exponent of something relatively new to Australian sport. As late as the 1950s, a local champion, playing football or cricket, usually with a stiff upper lip and poker face, did not publicly congratulate himself when he performed a feat on the field. Now, in contrast, Warne invited his fans in the grandstands and the outer to join him in celebration, the coloured cricket ball held aloft like a magic token. He invited spectators to join in the rejoicing to a degree hitherto rarely seen. Sometimes, after confounding a batsman with his spinning of the cricket ball, he would celebrate as if he had just landed on the moon.

At his statue a few days ago, the area of flowers, messages and alcoholic gifts had trebled since my last visit. Petals and leaves had fallen from wreaths, revealing other gifts. Several personal messages gave him monarchical status, addressing him in capital letters as King. Some addressed him simply as Warnie. One toy cricket bat carried a message straight from the heart: “You Will Be Missed.”

Geoffrey Blainey’s most recent book is Before I Forget: An Early Memoir.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout