Scott Morrison shifts for a changing world

The Prime Minister has to balance competing agendas with the US and China.

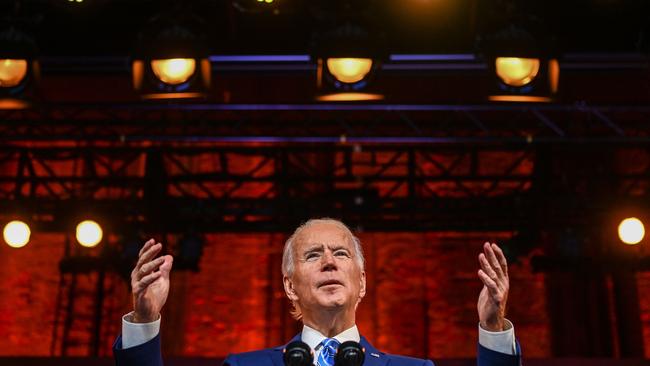

As president-elect, Joe Biden is signalling his foreign policy priorities — an outward-looking, Trump-repudiating, multilateral, pro-green, Asia-orientated outlook — and leaders around the world, Scott Morrison conspicuous among them, are changing their messages in response to a changing world.

Morrison is an optimistic about the coming Biden administration with early signs that Biden, an insider veteran, is an institutionalist, a pragmatist and a problem solver with a firm view of his foreign policy principles and, with China, likely to de-escalate the rhetoric but retain US competitive resolve.

Biden will be one of the most experienced foreign policy presidents to take office in the 75 years since World War II. His focus will be the global and US economic recovery, with the priority being job creation; witness his selection of former Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen, a labour market economist, as Treasury Secretary, an appointment that heartens Morrison, who knows Yellen from her previous job.

This week Morrison sent a series of messages but his most important theme — tricky but critical — is for Australia’s status as an independent player to be better recognised, as a nation allied to the US, interdependent with China but pursuing its “own unique interests”.

Morrison was blunt: he said Australia is “wrongly seen” by some solely through “the lens of the strategic competition between China and the United States”, asserting this was both “false” and a perception that “needlessly deteriorates relationships”.

The Morrison government’s big hope is that the Biden administration will give Australia more space to operate between America and China. Alluding to US-China competition, Morrison said that “our preference in Australia is not to be forced into any binary choices”.

Signalling this hopeful outcome from future president Biden, Morrison said: “We all need a bit more room to move.” That’s the point. He expects Biden and his team to bring more consistency to US-China ties and to lower the temperature, while believing that Biden will be far tougher on geo-strategic competition with China than was his former boss, Barack Obama.

This may work for Australia over time. But Australia-China relations face a protracted period of punitive actions, the latest arising from China’s imposition of duties from 107 to 212 per cent on our wine exports, a decision Trade Minister Simon Birmingham called “grossly unfair, unwarranted, unjustified”, based on a “falsehood” that was “completely incompatible” with commitments China has given under the bilateral free trade agreement and through the World Trade Organisation.

Much of the diplomatic damage is done. Australia’s task now is to avoid kicking back and only making the situation worse — and potentially it can get a lot worse. The irony is that in his path-breaking UK Policy Exchange virtual address last week, Morrison said: “It’s very difficult, I think, to understand the mind of China and their outlook. But it is our task to seek to do so. Of course, there are tensions. I won’t deny that. But I do feel that many of the tensions are based on some misunderstandings.”

Australia is responsible for some of those misunderstandings. But Morrison has made a critical point — he believes China has misunderstood Australia and that conclusion must necessitate a corrective response.

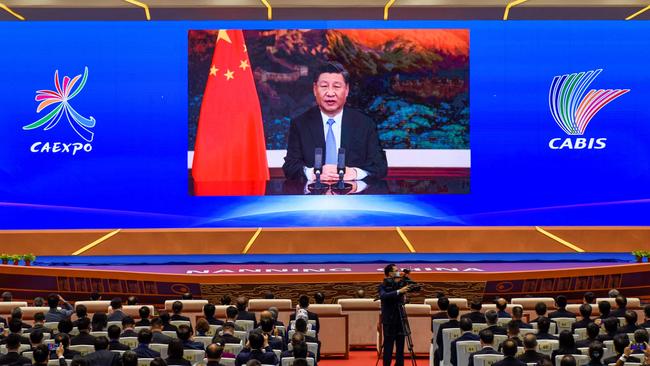

The PM, naturally, would like to break the ice in a meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping — given a Biden-Xi meeting is certain to occur at some time — but Morrison will not accept an Australian retreat from core policies as the price of dialogue. The reality is that plenty of scope exists for Australia to recast its messaging to China short of any sellout of principle. This is the direction in which Morrison seems to be heading.

Australia’s task was vested with global significance last week by prominent US strategic analyst Fareed Zakaria, giving the 2020 Lowy Lecture where he called Australia “the pivot country”, testing what many nations yet face — its ability to retain its economic partnership with China while “pushing back” against China, an analysis close to Morrison’s own remarks.

Zakaria identified a truth dawning on many nations from Asia to Africa: “As you watch Chinese imperialism, you’re gonna get very nostalgic for American imperialism.”

Morrison made clear there will be no change to Australia’s overall strategic position. He said “Australia desires an open, transparent and mutually beneficial relationship with China” while “absolutely committed” to its alliance with the US as its security bedrock. Given these operating axioms, the challenge, Morrison said, is “not straightforward” — an understatement. But in a rapidly changing world there remains scope for an Australian rhetorical and diplomatic adjustment.

Meanwhile, Morrison sent a range of substantial messages this week — that Australia, alert to Biden’s liberal instincts, wants a renewed emphasis on multilaterism and a rules-based global order as an alternative to policies of “containment”; that Australia’s impressive performance on COVID-19 is now a foreign policy instrument and marketing tool for our governing competence, medical/scientific ability and a source of ongoing appeal for future skilled migrants; and that his government, aware of rising global pressure on climate change, has modified its stance to say it wants the net-zero carbon emissions target achieved “as quickly as possible”, but by technology not taxes.

Morrison will look for ways to underwrite fresh Australia/China economic collaboration. He would welcome a dialogue if China is interested in joining the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade arrangement, since Xi raised this at the recent APEC meeting. In his UK address, Morrison told British PM Boris Johnson Australia looked forward to the UK-Australia free trade agreement and Britain potentially joining the TPP.

With Biden pledging to reassure US alliance partners, and incoming secretary of state Tony Blinken talking of “equal measures of humility and confidence”, Australia-US relations will revert to more pre-Trump cohesion reinforced by public opinion because Biden will enjoy a far higher approval rating than Trump among the Australian people.

“This is not a third Obama term,” Biden said. “We face a totally different world.” He knows there is no simple return to the world before Trump. But the Morrison government will have no complaints if Biden adopts a more forceful approach than Obama’s “leading from behind”, although it won’t share his expected human rights moralising.

The Morrison diplomatic style is becoming more apparent — he stands by enduring principles and positions yet constantly reinterprets them as a pragmatist adapting to shifts in a rapidly changing world. Australia must look confident of its beliefs but not succumb as a prisoner of dogmatism. Morrison’s compulsion, always, is to get on the front foot but this involves the risk of domestic overselling of foreign policy and security policy initiatives.

Australia is unsurprised by Biden’s appointment of former presidential nominee John Kerry as a cabinet-level special envoy for climate. This is Biden’s pivotal concession to progressives, though, to be fair, Biden believes in strong climate change action. He is authorising Kerry to change the global politics on climate and press for more action from the parties, a stance with the potential to embarrass the Morrison government — but Morrison, however, is sensibly moving to adjust position.

With the UK host of the November 2021 climate change conference in Glasgow, Morrison has told Johnson he wants to work together “on our shared task to create a pathway to net-zero emissions”, with the main question being not “if or when” but “how”. Morrison said Australia wants decisions based around “practical, scalable and commercially viable technologies, not economy-destroying taxes”.

Biden and Kerry will be constrained by the US congress. But that won’t stop them running global campaigns on more ambitious emissions reduction targets. There is one certainty: Morrison won’t be changing Australia’s 26-28 per cent emissions reduction target at 2030, no matter who asks.

Morrison knows from private talks with other leaders that some are clueless about how they will achieve net zero at 2050. Hence his stance: “Our focus on technology reflects our firm belief that targets must go hand in hand with practical action and a clear pathway to their achievement or they risk becoming only symbolic.” His aim is to work with Johnson to make the Glasgow meeting “a major step forward” — in domestic terms this means preparing his defences against the progressive movement’s political onslaught against him on emission targets.

Morrison is tracking Biden’s wavelength over a new brand of US leadership. Pledging last week to “restore America’s global leadership and moral leadership”, Biden hammered the line that “America is back, ready to lead the world, not retreat from it”. We must await what this means exactly. It will be far harder than Biden’s breezy optimism.

But Morrison said: “The commitment of the incoming Biden administration to multilateral and regional institutions is critically important. He’s relayed that to me in our first conversation. US weight and convening power is vital to preserving the rules, norms and standards of our international community, including in the Indo-Pacific.”

Australia’s multilateral diplomacy has been conspicuous in recent times — promoting Mathias Cormann as next secretary-general of the OECD, trying to keep alive the World Trade Organisation, working through the G20, support for the World Health Organisation, backing a global pandemic treaty and as invitees to recent G7 meetings where ideas have been floated about expanding the G7 into a larger forum for democracies.

But Morrison retains his entrenched philosophy about the global institutions: they work only as instruments not to “subjugate” the nation-state but as building blocks to promote mutual benefits across nations. His firm view, given the turbulence of contemporary global politics, is that alliances, structures and international institutions are more important than ever. Yet he sends the progressive left a sharp message: the only real authority of these institutions “is that afforded to them by sovereign states”.

A big theme Morrison is developing in global forums is the imperative not to derail world economic recovery. He worries that redistribution, re-regulation and green economics may get priority over growth and job creation as the world emerges from COVID-19. Contrary to some leaders, Morrison said: “We don’t need to ‘reset’ our economic agenda, we just need to get on with it.”

He warns the pandemic-induced recession is exactly that, not “the failure of world capitalism or liberal, free-market-based values”. This contrasts sharply with the sentiments coming from progressive leaders.

Morrison’s regional messages reflect two principles — economic inclusion and strategic stability. “Australia is not and has never been in the economic containment camp on China,” he said. This partly reflects Australia’s differences with defeated Donald Trump’s bilateral retaliation against China and his effort to drive a decoupling strategy from China. But it sits in tension with Australia’s far tighter rules governing foreign investment from China.

Morrison laments that “two of the most important economies in our region — the US and India” have opted not to join the TPP and 15-nation Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership respectively. Australia’s view is “straightforward” — we would welcome them joining. Morrison said: “The world will not recover from the COVID-19 recession if we trade and invest less or relinquish hard-won lessons on market-led wealth creation.”

On strategic stability, Morrison wants to see regional powers “stepping up” and asserting themselves against the common view that everyone must fall into a pro-China or pro-US divide. This is a simplification when virtually all regional nations have China as their major trade partner and many seek an active regional role for the US as security insurance or as a power balancer.

Morrison said under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, India’s regional contribution “has never been more influential while its economic weight has never been more consequential”. On Japan, he quoted new PM Yoshihide Suga, saying the deepening Japan-Australia security and defence relationship had become “increasingly important” to regional stability.

Despite Biden’s confidence, his task of reasserting US leadership post-Trump will be dangerous. The liberal internationalism that Biden champions is the precise outlook that Trump demonised in his creation of a grassroots revolt that took him to the White House in 2016. Biden’s executive team knows it must tie foreign policy into hard domestic results and jobs at home. Without that, he fails.

Yellen’s appointment is significant in this sense. She is a credible economic hand, a strong supporter of more US fiscal stimulus and ideally placed to ensure fiscal and monetary co-ordination in the urgent task of American job creation, Biden’s number one priority. America’s failure to manage COVID-19 means, in effect, it must await a vaccine for any sustained recovery.

Having adults back running US policy under a consistent president must constitute a plus for Australia. Biden will look for niche opportunities to co-operate with China and that will help Australia. The orthodoxy of Biden’s team is a pointer, Kerry apart, to the Indo-Pacific being a significant priority.

The task for Morrison is to navigate a path with China between antagonism and appeasement. And it will be much harder than that sounds. His three main problems will be getting China to listen and rethink; containing the anti-China sentiment building in this country; and ignoring the fatalists at home who believe China is locked into a stance of strategic hostility from which there is no respite.

Morrison said this week patience was important in dealing with China. That’s right. But his remarks also reveal he knows patience is not enough. Morrison has plenty of activism and pragmatism in his toolkit and they need to be deployed in that diplomatic space where Australia must operate in order to change the atmospherics with Beijing.