School key for First Nations children with free scholarships, on-the-job training

‘I’d like to work in a big company and travel the world.’ How educational interventions inspire Indigenous kids to spread their wings.

Wide-eyed with wonder, Aboriginal teenagers from the Northern Territory marvel at the views over Sydney Harbour from the top of Deloitte’s skyscraper at Circular Quay, 3000km from home.

For most of the Katherine High School students, this is their first trip out of the Territory – and the interstate excursion has sparked ambition and inspiration.

“I’d like to work in a big company and travel the world,” proclaims Shannon Devery, a 17-year-old student who hopes to study a business degree next year.

Sixteen-year-old Joshua Smith also aspires to a university education after the trip this week, organised by his “amazing teacher and leader”, English and humanities head teacher Greg Miller.

“He’s been a major encouragement for me to finish school and find bigger pathways,’’ the year 11 student says. “Before leaving I was thinking of keeping my part-time job based in Katherine, but now I’ve left there and seen Wollongong University, gone surfing and been here at Deloitte, I might go into a university pathway.

“You can drive for three hours here and still be seeing buildings taller than you’d see in Darwin.”

Miller, a corporate high-flyer who switched to a career in teaching through Teach for Australia, has tapped into his business network to create opportunities his students could only dream of experiencing.

“The whole idea of the trip is to empower young people to see opportunities in front of them, to build confidence and try new things,” he tells Inquirer.

“School attendance is a challenge in a remote area. We’re trying to wrap our arms around our cohort and show them the different opportunities available post-school, rather than sitting in a classroom and telling them. We’re showing them what’s possible.”

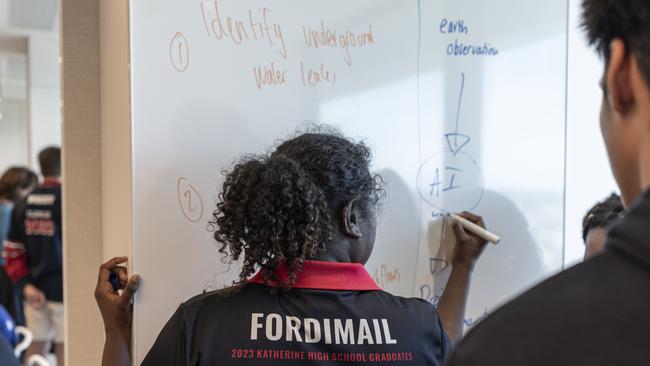

During their week-long trip, paid for through fundraising and philanthropic donations, the 17 students have visited the University of Wollongong, networked with students from Kiama High School and met executives from Deloitte. They’ve attended workshops to discuss how space technology can solve problems in their communities, such as monitoring water levels and keeping health workers safe when travelling 400km between jobs.

The Katherine excursion is one of myriad grassroots initiatives making a difference to the educational outcomes of First Nations students. From art workshops to business mentoring, boarding school scholarships and catch-up classes in literacy and numeracy, industry and philanthropists are co-operating to keep kids at school and launch them into work or further study.

As Australia debates the Indigenous voice, education needs to be acknowledged as a path to reconciliation and equality, health and wealth, for the generation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children trailing behind their non-Indigenous classmates.

In the federal budget last month, the only major new investment for education was $40m in extra money for 46 schools in Central Australia, which federal Education Minister Jason Clare secured after speaking to principals working in schools with high numbers of Aboriginal and underprivileged students.

Averaging $870,000 a school, the cash will pay for extra teachers, including Aboriginal staff to support cultural connections, and specialist teachers to provide intensive foundational literacy and numeracy support. Children with a diagnosed disability will be given extra help in class, and high school lessons will be made more flexible and relevant so students can obtain qualifications that align to jobs in their communities.

“If you’re from a poor family, the bush or you are an Indigenous Australian, you are three times more likely to fall behind at school,’’ Clare tells Inquirer. “For a lot of kids in Central Australia, it’s a triple whammy. Attendance rates are lower, NAPLAN (national literacy and numeracy test) results are lower, and high school completion rates are lower than almost anywhere else in the country.”

Indeed, the latest 2021 census data shows that Indigenous students are four times likelier to drop out of high school before finishing year 10. Among Indigenous Australians in their 20s, barely half have finished year 12, compared with 83 per cent of non-Indigenous youth the same age.

Even when they stay enrolled at school, Indigenous children are likelier to miss classes. Three out of four Indigenous students from years 1 to 10 missed the equivalent of a day of school every fortnight last year, compared with half of non-Indigenous kids.

This educational handicap continues in university, where Indigenous Australians are half as likely to be studying for a degree. Barely 2 per cent of university students have First Nations heritage, even though Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders are 4 per cent of the population.

Similarly, First Nations teachers make up only 2 per cent of the school workforce.

To turn the trend around, the University of Wollongong is sending its own Indigenous students to tutor teenagers at disadvantaged high schools. Enrolled in degrees ranging from environmental science to social work, psychology and teaching, the 32 “ambassadors” work part-time to tutor and mentor year 8 students from 13 disadvantaged high schools stretching from the Sutherland Shire in Sydney’s south to the Victorian border and inland to Goulburn.

“We build their aspirations,” says Jaymee Beveridge, director of the Woolyungah Indigenous Centre, which runs the program with the Aurora Education Foundation. “You can’t be what you can’t see.”

The tutors use teaching materials devised by an Indigenous high school teacher, based on pop culture to keep the kids interested.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students, as a group, are most likely to struggle with literacy and numeracy at school. Eight per cent of Indigenous children nationally have English as a second language – including three-quarters of five-year-olds in the Northern Territory, who speak an Indigenous language at home. These children are doomed to start behind their classmates in year 3 and fall further behind every year.

By year 9, one in three Indigenous students reads below the minimum standard, compared with one in 11 non-Indigenous classmates, based on the most recent 2022 NAPLAN data.

This gap in foundational learning makes it harder for students to flourish in high school and “learn or earn” once they leave, translating to a lifetime of lower pay and higher levels of unemployment.

Among First Nations students who drop out of school before year 10, only one in five will find work, compared with 79 per cent of those with a university degree, based on Australian Institute of Health and Welfare research from 2021.

Some enlightened employers are resorting to direct action to remediate failures in the education system. The National Electrical and Communications Association, through its emPower program, has provided life-changing tutoring and apprenticeships to 250 young Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders from Arnhem Land to outback NSW and western Sydney.

Adam Wilson, 25, graduated this year as a licensed electrician, working on the Metro project in Sydney, after completing a four-year electrotechnology apprenticeship with NECA.

“I don’t think I would have made it to here otherwise,” he says of the apprenticeship. “There were a lot of things in my life that pushed me away from school, and I was in a bad place at the time.”

Wilson found the focus on academic marks to attend university was a turn-off at school. “A lot of the pressure of going to university needs to be removed,” he says. “From year 9 to year 12 it was all about getting good grades to get into uni, and if you don’t get in your life’s over and you’re a failure. That conversation needs to change. I didn’t realise the benefits and perks of trade work until after I left school.”

NECA kickstarts each apprenticeship with a 10-week intensive course in remedial reading, writing and numeracy. NECA general manager of training and apprentices Tom Emeleus says 90 per cent of candidates had dropped out of high school.

“They’ve fallen through the cracks, and they need the basic literacy and numeracy they’ve missed out on in the schooling system, as well as employability skills,” he says. “We get halfway through the program and shift the start time to 7am. A lot of candidates have lost the connection to culture and country, so we have elders spend time with them and teach them about bush tucker and medicine and artefacts. It helps with their self-esteem and motivation.”

Emeleus says the program is changing lives. “We’ve got a lot of apprenticeship candidates who come from multigenerational unemployment, incarceration and substance abuse,” he says. “We have young men with fathers, uncles and grandfathers who didn’t work or are in prison. But now they’re in a hi-vis shirt, earning a regular wage and with a sense of purpose. Once the guys have got a (trade) licence, the whole world’s at their feet.” Now that many government infrastructure contracts require a quota of First Nations apprentices, he says, “every kid who’s job-ready is fought over” by construction companies.

Across the continent, the Saltwater Academy charity is using art and music workshops to build on the interests and strengths of Aboriginal children in the remote West Australian communities of Fitzroy Crossing, East Kimberley, Frog Hollow and Broome.

Graphic artists, illustrators, sculptors and photographers – among them Indigenous illustrator and children’s author Ezsra McKenna – inspire children with creative outlets and career paths connected to First Nations culture.

“The schools tell us that the day they have an Indigenous artist come to their school, it’s often the highest attendance rate all year,” says academy co-founder Cara Peek, a Yawuru Bunuba woman.

“School attendance is tricky in Indigenous communities where English is often not their first language. School is not often seen as something that has served their parents and grandparents well, so there’s no real drive to go. And then there’s the lack of food security in some communities – and you can’t learn if your tummy hurts because you are hungry.”

For academically driven students, big business is teaming up with the Australian Indigenous Education Foundation, a charity that provided boarding school scholarships to 343 students from 162 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities last year.

Graduates have been given internships by sponsors including BHP, Qantas, Sky News, SAP, the Commonwealth Bank and HSBC, or gone on to university to graduate as doctors, lawyers, teachers and business executives.

AIEF executive director Andrew Penfold says students thrive in boarding schools with “high expectations and teaching quality”.

“Students get 24/7 support in terms of classes, homework and tutoring, three healthy meals a day and they go to bed tired after a full day of school and sport,” he says. “I’m not suggesting boarding school is the answer for every kid, but we’re here to open the door for kids who want to go.”

Fifty children put up their hands for every 10 scholarships on offer. “The demand is coming from Indigenous families and communities, and the students themselves,” Penfold says. “Education is the key to closing the gap in unemployment, income levels, health and life expectancy. These kids become role models, showing what they’re capable of doing and inspiring the younger generations. There’s a real ripple effect.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout