Russian Orthodox Church still reluctant to acknowledge late royals

It is 25 years ago today that most of the Russian Royal family was buried in a state funeral, but the remains of the youngest children are still held in an archive.

The last tsar of Russia, Nicholas II, had much in common with today’s bullying Russian autocrat, President Vladimir Putin: He took the advice of hawks in his administration and opposed reforms, and he tried to extend Russia’s empire, in those days to its east, but was beaten back by a smaller, more aggressive force – Japan.

The tsar could have won the first Nobel Peace prize in 1901 and was nominated in the category to be awarded to the person or people who “have done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses”.

Remarkably, Putin, who had attacked and annexed the Ukrainian territory of Crimea early in 2014, was nominated for the Nobel Peace prize in 2020. He didn’t win and the details of his nomination will be kept secret for the next 47 years under Nobel rules.

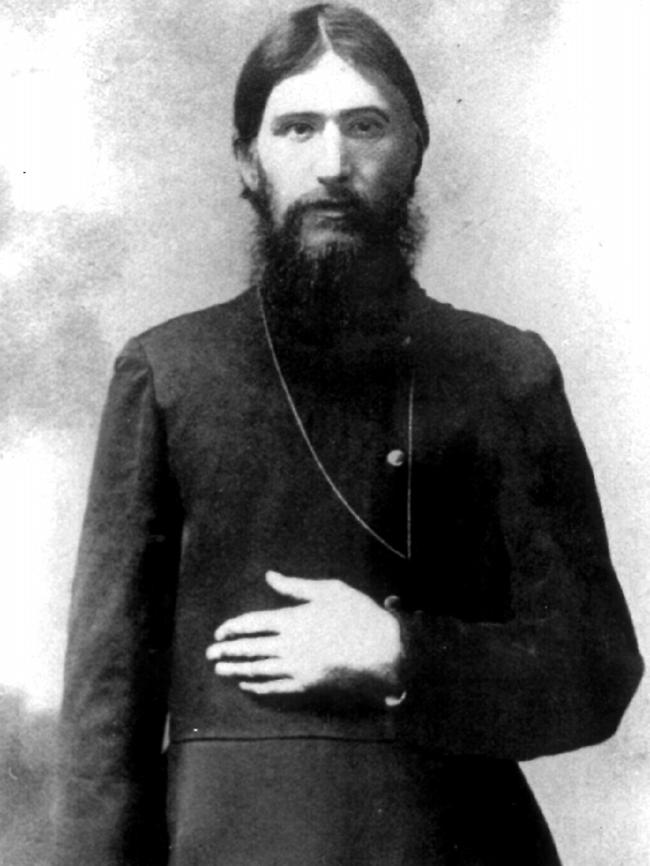

Also, the tsar, through his wife, came under the influence of a holy man, famously the legendary mystic Grigori Rasputin; Putin’s holy man is Vladimir Mikhailovich Gundyayev – Patriarch Kirill – leader of the Russian Orthodox Church. Kirill enjoys being part of the problem and has encouraged his leader’s fascism.

Days after Putin’s illegal, murderous invasion of Ukraine began, Kirill declared in his sermon: “We have entered into a struggle that has not a physical, but a metaphysical significance.” He does not accept the Ukrainian church’s independence and appears happy to wrest it back through the mass butchering of innocents – men, woman and children – an unlikely position for a so-called man of God.

History shows the relationship between Russia’s leaders, and the former royal family, and the powerful Orthodox Church is tangled, tricky and sometimes perilous. It is 25 years today since the remains of the Romanovs – Tsar Nicholas, his family and their remaining servants – were buried in Saint Petersburg’s Saint Peter and Paul Cathedral, 80 years to the day after they were shot and bayoneted to death in murders almost certainly sanctioned by Vladimir Lenin.

There had been two revolutions in Russia in 1917: the impetuous, unorganised February rebellion (it took place in March, a confusion of the Julian calendar then still used in Russia), whose “provisional government” was a hastily concocted union of various, but competing, interests including soldiers and politicians, but still seen as privileged by the country’s innumerable workers and peasants.

Food shortages continued, Russia remained committed to World War I – and was being humiliated, suffering huge numbers of casualties. Record keeping was thoughtlessly casual but researchers estimate that perhaps two million were killed and many more than that held as prisoners of war. Russia’s economy was ruined, its people in distress. It was fertile ground for Lenin and his Bolsheviks who then triumphed in the infamous October Revolution that changed much of the world (but which took place in November – Julian again).

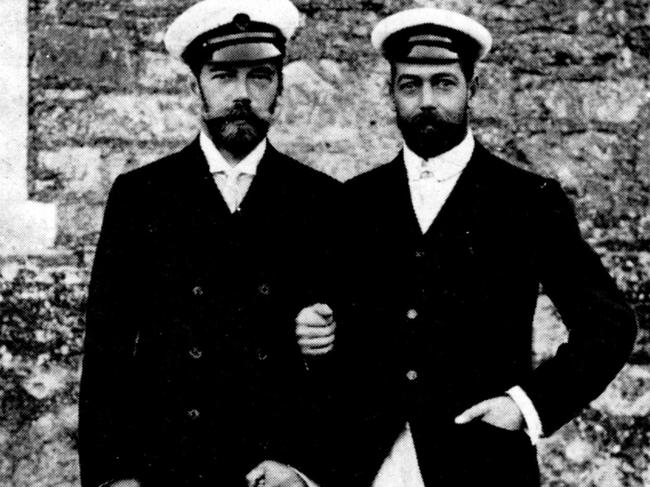

The first of 1917’s revolutions saw the Romanovs in comfortable exile at a palace south of St Petersburg, while Nicholas and wife Alexandra, both first cousins of England’s King George V, tried to negotiate asylum in London. They were close friends: “I look upon you … as one of my oldest and best friends,” George wrote to Nicholas years before of his doppelganger. Queen Victoria was astounded at their physical similarity.

Reluctantly, and despite noisy opposition by many members of the House of Commons, blood proved thicker than water and George V agreed to the family living in exile in England. This offer may later have been withdrawn. In any case, it was too late. The Romanovs were soon moved in a series of train trips to the governor’s house at Tolbosk, in Siberia, almost 3000km east of St Petersburg. At first, this too was bearable, but under house arrest they remained unaware of the threat the rise of Lenin posed to them. Newspapers for them were banned, so too their doctors, they were put on a prison diet, their windows covered and they were allowed out for two short exercise sessions daily. With vague plans afoot to possibly liberate the family, it is believed Lenin then moved. The family were sent south to a house in Yekaterinburg.

At midnight on July 17, 1918 – 105 years ago today – they were woken and told to assemble in its basement. Yakov Yurovsky, 40, their head guard, had arranged guns and bayonets. He read out a short execution order, to which Nicholas reportedly responded “What, what!” before being felled with the rest in a chaotic hail of drunken bullet fire from every direction. The room filled with gunsmoke and dust. When it cleared, Yurovsky’s men bayoneted the survivors and then used the butts of their guns to finish the job.

They stripped the bodies of clothing and jewels, burned and dynamited the remains, and buried them, but changed their minds and took them deeper into the forest and buried them again. The two youngest children, Maria and Alexei, were buried further away.

So few people knew the facts of their murders – Yakov died, possibly poisoned, in 1938, others were murdered by Stalin – that the Romanovs became one of the great mysteries and legends of the 20th century. The Bolsheviks announced the tsar’s death in the official newspaper, Pravda (ironically the Russian word for truth): “Nicholas Romanov was essentially a pitiful figure … the personification of the barbarian landowner (an) ignoramus, dimwit, and bloodthirsty savage.” But Lenin insisted news of the deaths of the entire family and their servants be kept secret. They were reported to be safe and alive under house arrest. He had the house they died in renamed the Museum of the People’s Vengeance.

Throughout the 20th century, various impostors claimed to be Anastasia, the Romanovs’ daughter who was 19 when the family were murdered. The most persistent of these was a mentally ill Polish woman, Franziska Schanzkowska, who, adopting the name Tschaikovsky and then Anna Anderson, pursued her claims for years between stints in psychiatric institutions.

In the 1970s a local geologist, Alexander Avdonin, began searching for the Romanov remains in the vicinity of the final residence and, aided by the details from aged locals, many of whom had heard the gunfire, he quickly found the bones of a group of adults and children and, in the clumsiest of exhumations – dug up and kept some skulls. Panicking that he might get into trouble, he reburied these. A decade later, after a friend of Avdonin leaked the story, the Romanovs’ bodies, but not those of the tsar’s only son, and his sister, were found in crude digs, at first involving a bulldozer.

Using a blood sample taken from Queen Elizabeth’s husband, Prince Philip, who was directly related to Tsar Nicholas’s wife, later DNA testing would confirm their identity.

Once this was positively established, Russian president Boris Yeltsin began planning the grand state funeral and burial ceremony. Twenty-five years ago today this was attended by many descendants of the Romanovs and almost every European royal family was represented, Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip by Prince Michael of Kent, whose grandmother, Grand Duchess Elena Vladimirovna of Russia, was the tsar’s cousin. Australia’s ambassador to Moscow, Geoffrey Bentley, attended along with diplomats from 26 other countries and the Holy See.

Yeltsin spoke bitterly of the crimes. “Dear fellow citizens: It’s a historic day for Russia. Eighty years have passed since the slaying of the last Russian emperor and his family. We have long been silent about this monstrous crime. We must say the truth: The Yekaterinburg massacre has become one of the most shameful episodes in our history.”

As the local communist boss at Yekaterinburg, Yeltsin had overseen the bulldozing of the house in which they were murdered lest it become a shrine to Russians yearning for the past.

The Russian Orthodox Church rejected the scientific confirmation the remains were the Romanovs and the then head of the church, Patriarch Alexy II, announced he would not attend. At first, like many senior Russians, Yeltsin baulked at attending, but swayed by sharp public opinion, changed his mind at the last minute. As a result of the boycott, the Romanovs’ names were not mentioned during the internment. “Their names only Thou, Lord, knowst,” was how it was handled.

In 2007 Alexie and Maria’s remains were found by a Russian builder curious as to their whereabouts. Sergei Plotnikov was prodding the ground when he heard “a crunching sound”. He believed he had hit a bone or a piece of coal. “We found several bone fragments. The first was a piece of pelvis,” he told a reporter. “We then discovered a fragment of skull. It had clearly come from a child.”

DNA tests proved their identity and the rest of the Romanovs were secretly disinterred for further testing in 2015, and some senior members of the church may now accept the identity of the family it has canonised.

Putin is reported to want to bring the family together and seal away that chapter of his country’s history, but the bones of Alexie and Maria remain in the State Archives, with the Russian Orthodox Church unwilling to accept them as necessarily being the tsar’s children. And Putin needs the support of the church that strenuously backs his war in Ukraine.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout