Robodebt report won’t fix debacle in policymaking

The real problem is the chronically unskilled public service and politicians overconfident about their ability to make stuff up and call it policy.

No one will be surprised at what is routine Canberra. Labor can claim it has a precedent for using royal commissions as political weapons. The Coalition’s 2015 Royal Commission into Trade Union Governance and Corruption served a similar purpose.

Not one of the 57 recommendations in royal commissioner Catherine Holmes’s Robodebt report looks at the behaviour of ministers. Only one recommendation calls for a cabinet-level decision: the gently worded suggestion that government should review “whether the existing structure of the social services portfolio and the status of Services Australia as an entity are optimal”. About 50 recommendations point to actions public servants could choose to do themselves. A handful require reform of legislation.

Ministerial bad behaviour is hissed at like spectators sledging Australian players in the recent Lord’s Test match, but hissing doesn’t change the umpire’s decision, and in the Westminster system the government is both lead player and sole umpire. And other than through elections, governments have no incentive to reform their poor behaviour or policymaking practices. Senior bureaucrats never publicly (and seldom privately) tell ministers they are making silly policy mistakes.

Governments have the whip hand over all aspects of setting up royal commissions and most often political imperatives rather than policy perfection set the pattern. Governments decide if royal commissions are held, they appoint the commissioner and write the all-important terms of reference.

Surprisingly, federal governments even get to choose whether to respond to recommendations. The Royal Commissions Act of 1902 is silent on whether a response is required.

In 2009 an Australian Law Reform Commission review into royal commissions and official inquiries concluded that governments should not be required by law to respond to such reports. It was enough that ministers “will be subject to parliamentary scrutiny in the normal way”.

Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus has said on the Robodebt report that “the government will now consider the recommendations presented in the final report carefully and provide a full response in due course”.

But the government’s statement on receiving the report makes it clear politics rather than improving policymaking comes first: “For almost five years, Liberal ministers dismissed or ignored the significant concerns that were raised, over and over again, by victims, public servants, community organisations and legal experts.”

Is anyone surprised that politics dominates a discussion about the conduct of public administration?

Holmes seemed to have one moment of puzzlement on that point considering the role of ministers’ personal staff. She rightly says ministerial staff are not public servants. They are there to serve a political purpose. She calls for a code of conduct that “clarifies their distinct role from that of the APS … and that the code clarify that such staff do not have authority to direct the APS”. Well, sometimes clarifying the obvious can be useful but note that this is not a formal royal commission recommendation.

Successive governments have fought off numerous attempts to set public service-like conditions for ministerial staff. Frankly, governments have been the long-term loser by insisting on keeping maximum flexibility over personal staff. A higher threshold of entry and clearer rules on roles and behaviour would protect ministers from some of their more indulgent recruitment choices.

Another area where Holmes treads lightly is on the roles of departmental secretaries. The imputation is that secretaries, at least in the Robodebt case, did not provide the “frank and fearless” advice so fondly imagined to be the best of the public administration. Holmes quotes an earlier public service review by David Thodey that found “the APS leadership favours being ‘agreeable’ rather than engaging in debate and challenge”.

I have met a few less-than-agreeable APS leaders in my time, but Thodey points to a deeper problem, which is that the public service has swung too far from being the producers of policy excellence towards what is euphemistically called being responsive – that is, doing what ministers tell them to do.

Recall the early days of Morrison’s prime ministership and a gathering where he effectively told public servant heads the government would do policy formulation and the bureaucracy should focus on mere implementation. It is remarkable how many politicians quickly come to the view in ministerial office that they are grand masters of policymaking, needing no help other than a blank canvas and an admiring audience.

Holmes backs Thodey’s recommendations that would have injected more rigour into selecting secretaries and strengthening their bargaining position, but again there is no royal commission finding or recommendation on that point, only a sense that the government’s position on the role of secretaries is “unclear”.

The Robodebt report does a solid job deconstructing one policy disaster and offering recommendations that would prevent it recurring. But the report has no fix for the continuing breakdown of policymaking in Canberra, or how to rebuild a chronically unskilled public service and how to corral a political class supremely overconfident about their ability to make stuff up and call it policy.

Peter Jennings is a former deputy secretary for the Department of Defence.

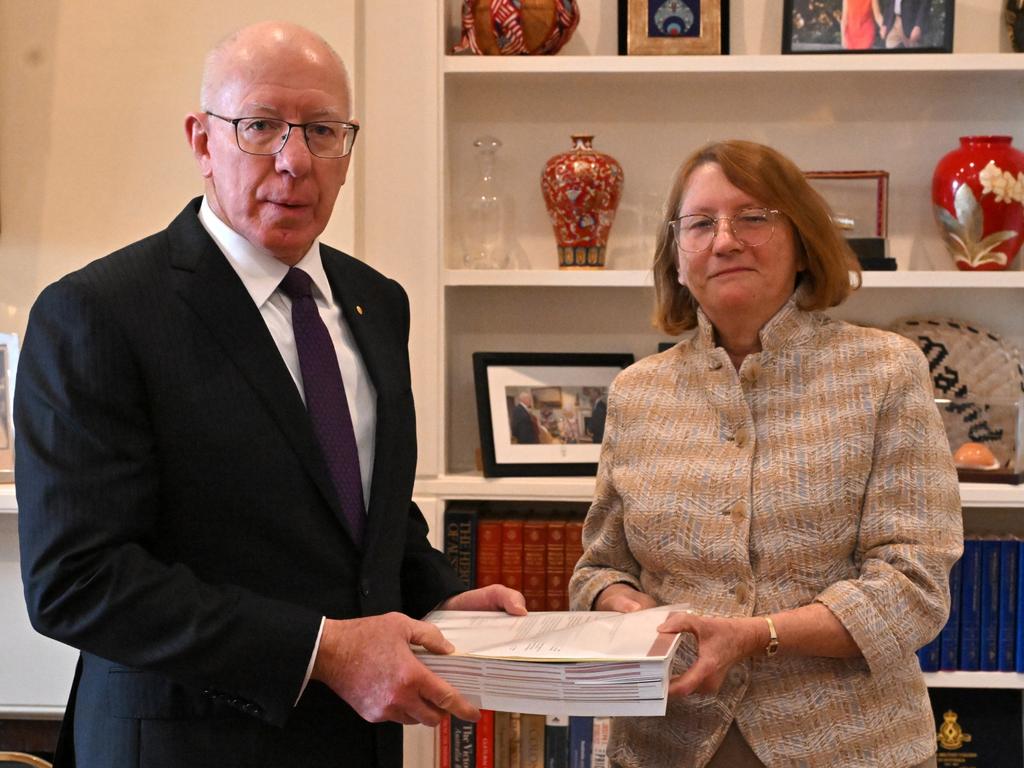

All 1000 pages of the Robodebt royal commission report are being used relentlessly by the Albanese government as a cudgel to bludgeon Scott Morrison out of parliament. A high-level review of policymaking is being made to serve a low-level political priority.