Right to know: the secrets governments keep

Government ‘safeguards’ for journalists send shockwaves through startled leaders of the legal profession.

When Christian Porter unveiled his new “safeguard” for journalists facing the prospect of criminal charges, it fell well short of what the media was seeking. But its harshest critics might well be the startled leaders of the legal profession.

Instead of reforming the overzealous use of secrecy laws, the Attorney-General has left those laws in place and simply will decline to enforce them against journalists he will select at his discretion. He has instructed the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions to seek his consent before prosecuting journalists for breaches of four federal secrecy laws.

The CDPP already exercises discretion over which matters justify prosecution but Porter describes the new procedure as “a separate and additional safeguard”. He has said in the past he would be “seriously disinclined” to approve prosecutions of journalists except in the most exceptional circumstances.

Yet the practical impact of this scheme has caused concern.

It means some of those in the Canberra press gallery will avoid the risk of criminal convictions and a term in prison for revealing government secrets. But those who are denied the benefit of Porter’s discretion still could find themselves with a criminal record.

- READ MORE:Morrison tested on secrecy laws |When politicians decide the news | Agencies’ media laws ‘flawed’ | State actor likely to stay secret | AFP top brass must be in loop

The executive branch of government — not the law or the independent CDPP — will decide who will be prosecuted. And the scheme applies only to journalists. That means whistleblowers who tell journalists about wrongdoing could go to prison. But some journalists who tell the world the same information will remain free — at Porter’s discretion.

If the Attorney-General expected praise for this scheme, it is yet to emerge. The leaders of the legal profession and the media industry have denounced it for introducing a moral hazard that could encourage compliant reporting of federal politics.

Instead of easing concern about excessive use of government secrecy, this scheme has introduced a new problem. It has triggered warnings that it leaves the way open for political interference in the enforcement of secrecy laws.

This assessment from former top prosecutor Nick Cowdery QC and legal academic Patrick Keyzer is in line with the critique of the scheme by the media industry’s Right to Know coalition.

Cowdery, a former NSW director of public prosecutions, was blunt: “When you have a power like that in relation to the exercise of a fundamental freedom, that is the exercise of freedom of expression and the freedom of the media, I think it is an unwarranted potential political interference in the conduct of a criminal case,” Cowdery says. “So I would be quite opposed to the attorney having power in relation to that.”

The media industry has pointed to the similarities between Porter’s scheme and the unqualified power the kings of England exercised before the balance in that country shifted decisively to laws approved by parliament.

Porter’s ministerial direction and his reluctance to prosecute journalists could be viewed, on first blush, as media-friendly. But only on first blush. Ministerial directions are not law; they can be changed and withdrawn at the stroke of a pen, and Porter’s discretion is not subject to judicial oversight.

The media’s Right To Know coalition believes this and other recent proposals from the government and its agencies are more reminiscent of “the historical and arbitrary monarchical power of grace and favour than substantive law reform”.

“In particular, the very width of the Attorney-General’s discretion not to proceed with the prosecution of a journalist, and the inevitably selective way in which that is to be exercised, should give rise to considerable unease within the community,” the media industry says in its latest submission to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security.

Cowdery’s concern is in line with that of Law Council of Australia president Arthur Moses SC, who believes the scheme “creates an apprehension on the part of journalists that they will need to curry favour with the government in order to avoid prosecution”.

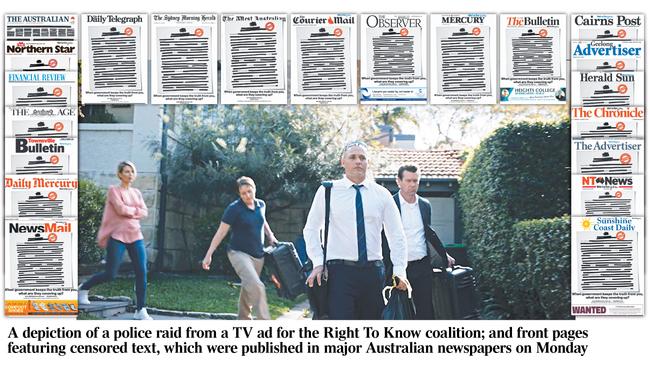

The Attorney-General unveiled his scheme after the mainstream media called for reform of secrecy laws after those laws triggered raids in June by the Australian Federal Police on the home of News Corp Australia journalist Annika Smethurst and the ABC’s Sydney newsroom.

Secrecy reform is part of a broad agenda that includes:

● The right to contest applications for warrants to raid journalists and newsrooms.

● Exemptions for journalists from laws that could see them jailed for doing their job.

● Better protection for public servants who reveal wrongdoing.

● Improved freedom of information laws.

● Defamation reform.

The government has not said whether it will make changes but Porter has left the door ajar. He told the ABC on Sunday that some of the media’s proposals were “sensible” while others “are right at the outer edge of workability”.

Keyzer, who holds a research chair in law and public policy at La Trobe University, says he has “no doubt” that if secrecy laws are causing problems, it would be better to amend those laws instead of introducing a system of selective enforcement based on the discretion of a politician.

When deciding which journalists should not face court Porter has said he will pay particular attention to whether they were “simply operating according to the generally accepted principles of public interest journalism”.

However, Keyzer and Cowdery point out that the new procedure is not “justiciable”, which means those who are denied the benefit of the Attorney-General’s discretion cannot challenge the decision in court and still will face criminal prosecution.

“It’s problematic because it places a politician in a position where he or she is going to have to exercise a discretion which is necessarily going to affect the media and their capacity to engage in fearless reporting of matters of public interest,” says Keyzer.

Cowdery agrees with the assessment that Porter’s scheme would create a moral hazard for journalists who might be tempted to suppress unfavourable news about the government in the hope of avoiding a future prosecution. He is also concerned that officials in Porter’s department will simply duplicate the processes of the CDPP, leading to a waste of public resources.

“The very real potential is that all of that industry will go for nothing and the Attorney-General will decide not to prosecute because of some politically connected reason and there will be huge wastage of public resources,” Cowdery says.

Keyzer warns that it could also place the Attorney-General in a conflict of interest whenever he is called on to decide if a journalist should be prosecuted for reporting developments that had embarrassed the government of which he is a member. “Given the importance of the issues at stake, it is very difficult to imagine a scenario that is more important to the welfare of the polity as a whole than free and frank reportage of the course of government decision-making,” Keyzer says.

The Right To Know coalition has supported a plan to reform federal secrecy laws that was first suggested by Bret Walker SC, a former independent national security legislation monitor.

Walker called for “overarching legislation that defines in a restrictive fashion what information must be kept secret”.

The media industry’s reform proposal calls for a new system of auditing and reporting to ensure senior public servants and ministers do not use secrecy laws simply to hide information they find embarrassing.

It is worth keeping in mind that police raided Smethurst’s home after she reported leaked information showing the departments of Defence and Home Affairs had been discussing the introduction of electronic spying on Australian citizens.

Nine years ago the Australian Law Reform Commission called for changes that could have prevented that raid.

The commission wanted secrecy laws reformed to protect disclosures that were in the public interest. And if a disclosure caused no harm, the commission believed nobody should be prosecuted. Both changes are backed by the Law Council.

Keyzer endorses another part of the media industry’s reform proposal, which would ensure the AFP is given permission to conduct raids on the media only after a hearing before a judge at which the media is represented.

Raids would be authorised only if they met a new test. The public interest in seizing information from a media organisation would need to outweigh the public interest in the right to be informed and the public interest in protecting public servants who reveal wrongdoing. The case for this change is directly related to the problems that emerged in the current system in which raids on the media are authorised at hearings where the AFP is the only party in court — increasing the propensity for error.

The raid on Smethurst’s home was authorised by a newly appointed magistrate at the start of his fifth week on the bench after a hearing at which the AFP was the only party represented.

The search warrant issued by this magistrate, which provides the legal basis for the raid, is subject to a High Court challenge that alleges it contains legal errors and is invalid on constitutional grounds.

The June raids took place almost five years after the Federal Court found that the AFP had misled magistrates when it obtained warrants for raids by about 30 police on the offices of Seven-West Media and two associated law firms.

After the raids, Seven sued and won. The warrants were quashed as defective and Tony Negus, who was AFP commissioner at the time, apologised unreservedly.

A Senate inquiry found that evidence presented to the inquiry, as well as a judgment by the Federal Court’s Jayne Jagot “suggest the AFP failed to communicate all relevant information to the magistrates responsible for granting warrants”.

There is every likelihood that the Seven raids would never have taken place if the media organisation’s lawyers had been present at the warrant hearings where they could have identified the AFP’s mistakes.

Because the AFP was the only party in court, nobody could point out that the AFP had failed to disclose that it held correspondence from Seven that undermined the case for the raids.

A contestable warrant hearing in that case could have prevented 30 AFP officers — some of whom were armed — from being diverted from fighting crime. It also could have saved Negus the embarrassment of issuing a public apology.

Instead of allowing the media to be represented at these hearings, some have suggested it might be possible to inject an equivalent amount of rigour by appointing a third party as a public interest advocate. But if such a system were in use at the time of the raid on Seven, it would have made no difference.

The media industry’s latest submission explains why: “Only the journalist or news organisation (that is) the subject of the warrant will have the relevant understanding of the matter they were investigating, and be able to articulate with the relevant background why it is in the public interest that the warrant not be issued,” says the submission.

Since the Seven raid, there has been no sign that things have changed. If anything the performance of state and federal police at warrant hearings has deteriorated.

In July, a report by the Commonwealth Ombudsman revealed that police had been conducting illegal searches of journalists’ metadata — or telecommunications details — after obtaining invalid warrants.

The Ombudsman found that the AFP obtained a journalist’s metadata without a warrant in 2017 and the ACT police accessed metadata with invalid warrants 116 times.

The AFP disclosed this year it had lawfully accessed the metadata of journalists 58 times in 2017-18 — which gives them the ability to track the media’s contacts with confidential sources of information.

Keyzer says the proposal for the media to be represented in court whenever the AFP seeks search warrants against the media was “a very worthwhile step”.

It would mean adopting a practice that has long been used in Britain. Instead of going to court after raids, Keyzer says “a proper argument in court” would take place before police entered newsrooms or journalists’ homes.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout