Riding the plastic merry-go-round

Rubbish is big business, a $15bn a year industry in Australia that is only starting to pique our conscience.

Sometime soon, Friends of the Earth is planning to place tracking devices secretly into Melbourne’s recycled rubbish stream to see where it ends up.

There is a one in four chance it will be a long journey beyond Australia’s shores, to somewhere in Asia.

That is unless a clampdown by governments in China, Indonesia and Malaysia succeeds in turning back the tide of mixed waste that has been openly traded as a partial solution to taming the developed world’s mountains of muck.

Rubbish is big business, a $15 billion a year industry in Australia that is only starting to pique the nation’s conscience.

Garbage erupting

As in a rubbish Mount Vesuvius, the pressures have been building since long before China shut it borders to unsorted waste in 2017.

Decades of underinvestment, inadequate kerbside separation by households, a global focus on the environmental impact of plastics and profiteering by local authorities are finally coming to a head.

It is an area laden with ideological baggage. High ideals for a circular economy are up against the reality that not everything can be recycled, certainly not for profit.

Everything is on the table — new imposts on virgin goods to promote reuse, government mandates to stoke investment and new rules on what exactly can be put on to the high seas.

Waste to energy

Waste to energy, turning waste into a form of electricity, heat or a fuel source, a standard feature of waste management in other parts of the world, is pushing hard to get a foothold in Australia.

In response to China’s ban on unsorted rubbish, federal and state environment ministers last year declared aspirational targets for 2025.

The targets call for 100 per cent of Australia’s packaging to be reusable, recyclable or compostable by 2025 or earlier.

At least 70 per cent of Australia’s plastic packaging will be recycled or composted by 2025.

An average of 30 per cent of recycled content will be used across all packaging by 2025 and single-use plastic packaging will be phased out.

Exporting the problem

The Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation was given the task to create a new vision for the waste that many of its members create.

The first step was to study where Australia’s waste stream comes from and where it goes.

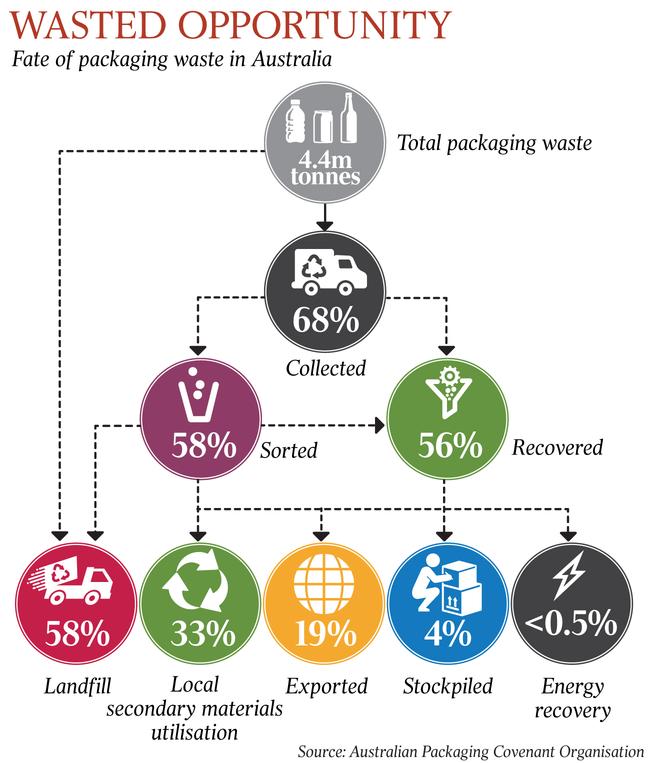

In a detailed report published this year, APCO says Australia generates an estimated 4.4 million tonnes of total packaging waste a year. A total of 68 per cent of the waste is collected, of which 56 per cent is recycled. This ranges from 32 per cent for plastics and up to 72 per cent for paper.

Waste exported represents a significant proportion of the total waste recovered.

It is a reverse of the old environmental maxim: think global, act local.

Rather than an industry of subterfuge, however, exporting plastic waste has been a two-way business opportunity.

Sam Cossar from Friends of the Earth says backloading empty cargo ships that have delivered goods from Asia has made it cheaper to ship mixed waste overseas for sorting and processing there. The result has been a less than thorough effort to sort waste properly at home into components that can be recycled.

Most exports have been mixed plastic and paper, which has a value for recycling. The receivers who get paid to take the paper still make enough money to dispose of waste plastic through other means.

Asia bins a regime

But as consumption rises across Asia, and a booming middle class demands better environmental protections, the old regime is no longer good enough.

China’s ban shocked the rubbish-exporting world but is now being followed by other countries, which are getting an increased spill-over of the rubbish that China refuses to take.

Recent changes to global trading arrangements make it possible for governments to refuse cargoes of unsorted waste.

For Australia, the bottom line is that the domestic market for used plastics is not big enough to absorb all of our waste.

Most recycled plastics in Australia are used to make things such as furniture, for which there is only limited demand.

Friends of the Earth is pushing government for public procurement of recycled plastic products but its bigger focus is on waste minimisation.

Others can see a future in which old plastics are used to make new roadways and broken bottles are repurposed into cement to build the Snowy Hydro 2.0.

Turning point

Australian Council of Recycling chief executive Pete Shmigel says this is a time of great opportunity, a turning point for the domestic system.

“We have benefited for the past 15 years from an export system but it is now not sustainable,” Shmigel says.

“There is a need for policies and investment in infrastructure, big decisions have to be made.”

Because plastic is a light material, it is costly to collect, sort and recycle.

“If we think it is a public good for the environment, we have to face the fact there is a cost,” Shmigel says.

“We can collect the money through rates, higher prices for bottles or to access the $1.5bn a year collected by local councils in waste disposal levies.”

Industry estimates are that only $100 million to $200m of that money finds its way back to recycling. The rest goes into general revenue.

APCO’s report estimates the municipal waste stream accounts for three-quarters of plastic packaging, much of which finds its way into landfill.

There are about 60 plastic reprocessors operating in Australia and mixed plastic makes up the bulk of plastic packaging recovered.

Recycling up in flames

But the China ban has undermined the economics of recovering mixed plastics as more intense sorting and recovery are required. The economics are difficult.

As a result, APCO says energy recovery — biological and thermal processing — “is likely to be a necessary final component to achieve very high recovery targets of more than 77 per cent, particularly if the amount of materials exported is limited in the future”.

“Deployment of these technologies at the right scale can support waste recovery and carbon mitigation objectives,” it says.

This is an incendiary proposition for those most passionate about recycling.

Jeff Angel of Boomerang Alliance, an association of environmental groups, says going down the waste-to-energy route risks losing a generational investment in recycling.

People would be less interested in sorting through their own garbage if they thought it was just going to end up in the furnace.

As it is, many are increasingly aghast that often recycled waste is being stockpiled, buried or sent to Asia.

Angel says a strategic mistake was made in not insisting kerbside rubbish be fully separated rather than mixed.

Incentives are needed to help build the circular economy, he says.

“At the eulogy to Bob Hawke there was a reference to how he reduced sales tax on recycled materials,” Angel says. “We could look at something like a GST exemption or put an impost on virgin materials.

“The other option is waste to energy, which is not recycling.”

It is counter-productive, he says, because waste-to-energy plants would require 20-year supply contracts, removing the incentive to invest in sorting and reuse.

Crunch time

Crunch time is coming, however. Construction has started on Australia’s first waste-to-energy plant at Kwinana in Western Australia.

Avertas Energy’s project has been supported by a $23m grant and up to $90m of debt finance from the federal government.

It will be able to process 400,000 tonnes of non-recyclable household, commercial and industrial waste a year when it begins operation in 2021.

Niels Jacobsen from engineering group Ramboll is overseeing development of the Kwinana plant.

He says it is not a case of either recycling or waste to energy but of both working side by side.

“It is all about education and doing things the right way,” he says. “There are a lot of plastic items that cannot be recycled.

“Waste to energy can be considered a form of recycling because it is using the energy component of waste to produce energy.”

Toxic debate

Jacobsen says 2200 waste-to-energy plants are operating worldwide, including in Europe, the US and across Asia.

He says concerns about toxic emissions have been overcome decades ago.

This is a message that has yet to reach NSW.

A long-running quest by Dial a Dump king Ian Malouf to build the world’s biggest waste-to-energy plant near Eastern Creek, in western Sydney, crashed and burned last year.

Malouf has cashed in his stake in Dial a Dump for billions to focus on super yachts but remains committed to pursuing the waste-to-energy dream.

The proposal was rejected in July last year by the Independent Planning Commission, which found there was “uncertainty in relation to the human health risks and site suitability”.

The project was found not to be in the public interest.

Malouf remains committed to the project through the company The Next Generation and has appealed against the planning commission decision to the Land and Environment Court.

Company spokesman Christopher Biggs says the plants are commonplace across Europe where they operate subject to the strictest environmental standards in the world. NSW has adopted the same strict emissions standard as Europe.

Things change and as Asian bans bite and the rubbish mountain grows, many believe waste to energy is only a matter of time.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout