Known as Mungo Lady and Mungo Man, the two Aboriginals lived some 40,000 years ago, though their lifespans did not overlap. Their home was not far from the meeting point of the inland rivers, the Murray and Darling. The colder continent they inhabited is not easily imagined and now rarely discussed, partly because it belonged to an earlier period of climate change which dwarfed the climate change widely predicted for us.

The two Mungo people – strangers to each other – were alive when the world map was radically different to ours. If they had possessed the knowledge and the energy they could have walked on dry land all the way from Lake Mungo to New Guinea. Or they could have walked south to the snow-capped mountains of Tasmania – Bass Strait did not yet exist. Eventually the great rising of the seas was to sever continental Australia from New Guinea and Tasmania.

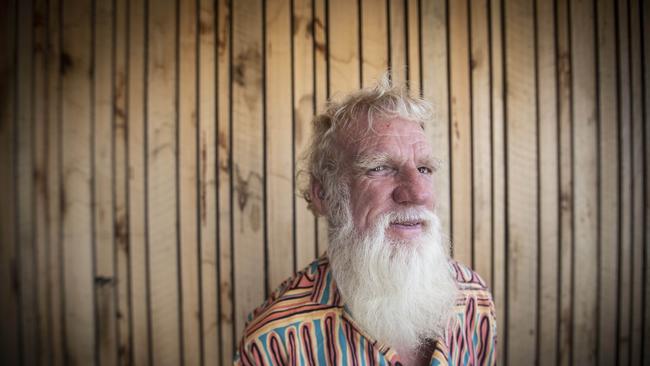

These two human remains, by far the oldest located in Australia, were found on separate journeys in 1968 and 1974 by Professor Jim Bowler, a Gippsland-born geologist who is still alive and deeply perturbed about the likely fate of the bones of these people who occupy a special place in the history of both Australia and the world.

It is the NSW government which has decided that the remains of the two Mungo people should secretly be buried in an unmarked place in their own homelands. It is the federal government in Canberra which in the next few weeks must decide whether to endorse or over-rule this decision.

As Lake Mungo and its neighbourhood is, like the Great Barrier Reef, one of our few World Heritage sites, this controversy could run far. It is of concern to the United Nations, to a variety of Aboriginal groups, to academics in many fields, and not least to Bowler, whose discoveries of the two Mungo remains have turned a dry lake into a place of world significance. Last week, on July 8, they learned from Canberra that they had the astonishingly short time of 10 days in which to submit their final viewpoints.

At the heart of this coming decision is the question: What did these two long-dead people do and think? It is the belief of most international scholars that they were hunters and gatherers who knew intimately the ecology of their own mini-nation, and intelligently moved camp according to the variety of foodstuffs that each season provided. Traditionally women gathered plant foods and the men hunted animals and birds.

In due course the overwhelming majority of the world’s peoples entered a new phase of history. They now lived in towns and relied mostly on domesticated plants and animals for their daily food. In contrast, Australia even as recently as 250 years ago remained an isolated showcase for a way of life that had vanished almost everywhere else. Mungo Lady and Mungo Man have become icons of that old way of life which once dominated every habitable land.

Schools are increasingly taught another version of history: a version which downgrades the Mungo people. Students are instructed to believe that Aboriginals were not nomadic but pioneers who lived permanently in the solid dwellings of townships that might hold up to 1000 people. They allegedly grew their own food and stored it in large granaries and little underground storehouses, and were so masterly in coping with varied climates that their happy little townships flourished “in every corner” of the continent, indeed even in the deserts.

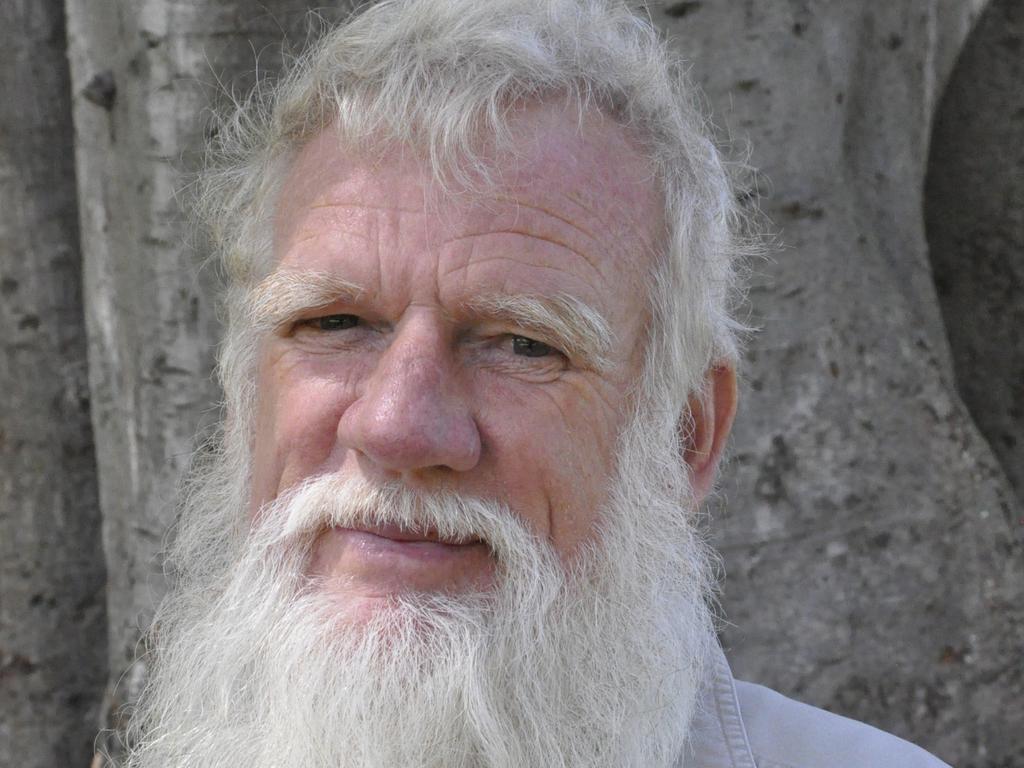

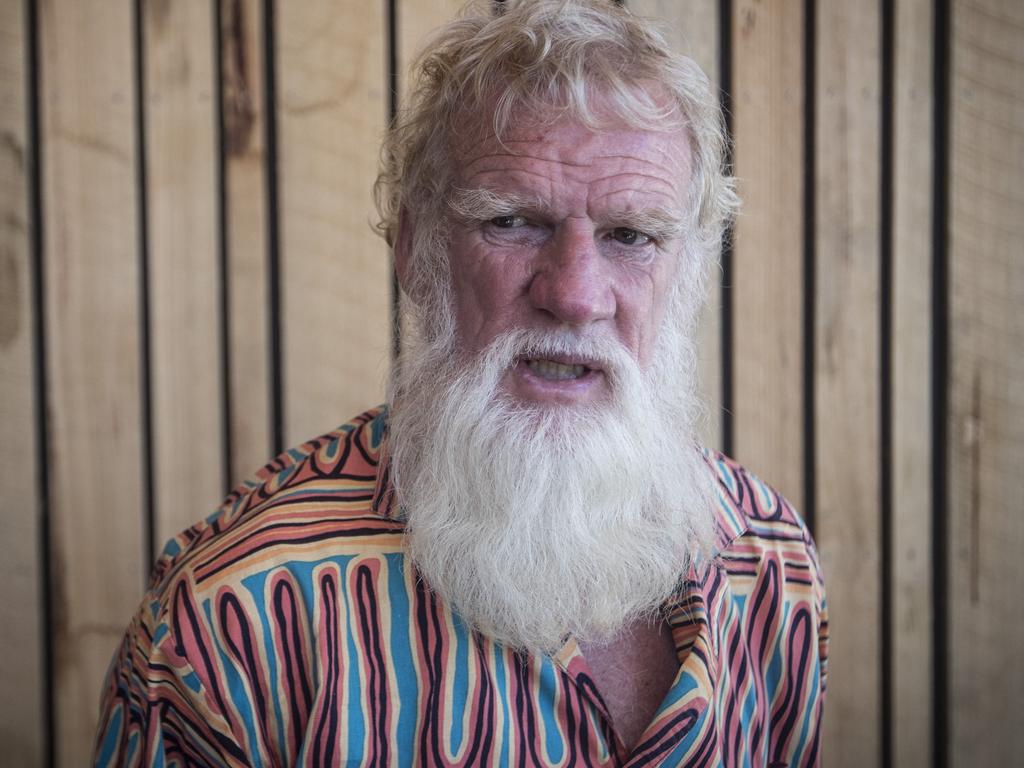

Bruce Pascoe, originally a schoolteacher, is the populariser of this recent revolution in understanding Australian history. In mistakenly contending that Aboriginals invented an early form of agriculture he extends praise to scholars on whom he relies. His popularity arises partly from the public’s illusion that he is really an Aboriginal historian who knows almost instinctively how his ancestors thought. He also claims that mainstream Australians deliberately hid the evidence which he now unveils.

His accusation of a gigantic cover-up is widely accepted by a variety of readers of his best-selling book Dark Emu. In federal parliament on February 12 last year, Anthony Albanese in a passionate and fluent speech declared: “In this one extraordinary book, Bruce has unearthed the knowledge that we already had in our possession – but chose to bury along the way.” Was Albanese thereby supporting Pascoe’s extraordinary theory on the origins of Australian democracy?

Aborigines, according to Pascoe, had created a system in which the male elders were the major governors. But surely that cannot be called a democracy either in methods or in spirit. Somewhat risky is Pascoe’s declaration: “Of all the systems humans have devised to manage their lives on Earth, Aboriginal government looks most like the democratic model”. Can that be true? If the Aboriginal system of government was democratic, then China today might also begin to seem more democratic.

Another revolutionary theory from Pascoe is that the Aboriginals created an ultra-civilised haven of peace which, almost unique in the world’s history, could be called “the great Australian peace”. His later book, Young Dark Emu, ends with the triumphant question: “Where else on Earth was there a civilisation that lasted more than 80,000 years”? Hardly any expert shares Pascoe’s insistence that Australia has been settled for 80,000 years.

While it is beyond doubt that a small number of Australian settlers killed a considerable number of Aboriginals, it is also certain that – long before 1788 – Aboriginal tribes were often at war among themselves. It is now common to minimise these battles, partly because they were over in a few hours and the deaths seemed few. The rate of death in the frequent wars was, however, high. The distinguished American anthropologist Lloyd Warner concluded that in a sparsely-peopled region of Arnhem Land where he did his fieldwork, about 200 Aboriginal men died from warfare between 1909 and 1929.

Professor Frederick Rose, one of the few scholars to live among Aboriginal peoples in the last phase of the tribal era, concluded that the Aboriginal deaths in battle were on a large scale. Pascoe read Rose’s book but must have skipped the pages where the bloody warfare is quantified. According to the Princeton historian and archaeologist, Ian Morris, the hunters and gatherers, wherever they existed, had a very high ratio of battle deaths (namely deaths in proportion to total population) compared to those living in our so-called “civilised” nations in the 20th century.

Influential educators seem slightly deluded in telling Australian children that the Aboriginals long ago had found the formula for international peace and that the childrens’ duty – when they grow up – is to persuade the UN to adopt that venerable Aboriginal formula.

To his credit, Pascoe is a lively and engaging lecturer especially to rural and Aboriginal groups, and his main book Dark Emu is very readable in many chapters. Some pages are like a friendly fireside chat in which he moves quickly from topic to topic. Some pages denounce the “brutal” European peoples or their Australian descendants at almost every opportunity. On one page they are said to be unlike the “kind” Chinese.

The landmark trophy which Pascoe achieved was for authors “of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent”, a prize initiated by premier Mike Baird of NSW and judged mainly on a book’s literary merits. In 2016, Pascoe’s prize was shared with a young Dutch Aboriginal author, Ellen Van Neerven. On the strength of his award, Pascoe was also judged eligible for the prized NSW “Book of the Year Award”, which he won. His career thereby received an enormous boost.

Dark Emu proclaims that his own Aboriginal ancestry embraces Bunurong and Tasmanian and Yuin peoples, but it is now known that his four grandparents were of English descent. Warren Mundine, one of the foremost Aboriginal Australians, and an expert in assessing a person’s claim to be Indigenous, has recently denounced Pascoe as a pretender. Most Australian readers would agree with Mundine that when a valuable prize is created to reward and foster Indigenous writers, an outsider should not be permitted to snatch the prize. If this happened in a major sport there would be a national uproar.

Pascoe not only has tried to revise the history of Australia but also turned upside down the geography. In his mind the vast Australian deserts were no obstacle to Aboriginal farmers, for he describes a prosperous chain of villages extending, millennium after millennium, right across the driest parts of the continent. This huge belt of country allegedly grew plentiful grains, whereas the wetter and cooler regions of Australia grew yams and other plants.

Each of the two books, Dark Emu for adults and Young Dark Emu for children, contains rival maps of Australia. Both omit the Torres Strait Islanders: real gardeners, they are therefore trouble makers upsetting his theories.

The vivid map for children is the more inaccurate. It depicts not only our present wheat belt but also a huge old-time Aboriginal grain belt which was about five times as large. What Pascoe should explain is that the Aboriginals’ could not always feed their own population whereas our present grain belt in a prolific year can feed at least 100 million people here and abroad.

This mythical Aboriginal grain belt is worth inspecting. It is said by Pascoe to embrace parts of four out of the five mainland states. It also embraces large parts of four deserts – the Simpson and Tanami, and Great Sandy and Gibson deserts. Not one of these deserts is drawn and labelled on Pascoe’s grain maps. As most of this huge Aboriginal grass seed zone – according to the official climate maps – includes the most variable and uncertain climate in all the continent, its average harvest must have been small.

Undoubtedly, traditional Aboriginal peoples collected grain in small quantities – when there was grain to collect – but they rarely if ever planted grain seeds at the start of the hoped-for growing season. Even in coastal regions with adequate and reliable rainfall the annual harvest would not be sufficient to provide grain for the coming 12 months, let alone for another couple of dry years that might appear. Pascoe forgets that part of the stored grain also has to be used as seed for next year’s harvest.

Readers are told that some of the stored seed found in one Aboriginal village equalled one tonne. Rod Gillespie, the head of one of Australia’s largest bakeries, in answering my query, explained that one tonne of the best grass seed would probably supply a permanent township of 1000 Aboriginal people with enough calories for only two days. Two days, when at least 365 days’ of food was needed, is a pitiful provision. Gillespie also pointed out that he was very optimistically assuming that the Aboriginal seed carried as many calories as the modern wheat seed which bakeries consume. My own estimate is that a few years of drought would lead to many deaths through starvation.

In academic circles the dominant view is still that Aboriginal success rested largely on the ingenuity of hunter-gatherers. This discovery, a revolution in Australian intellectual life, was accomplished mainly in the years after 1950. Pascoe fails to praise most of the talented promoters of this revolution. As for the skilled hunter-gatherers themselves, Pascoe calls them “primitives haplessly wandering across the face of the Earth”.

He goes out of his way to omit the success stories of these nomadic people. Thus he tells us about Donald Thomson, a distinguished Australian anthropologist, but ignores Thomson’s famous account of nomadic life in Arnhem Land and the logic and ingenuity of the seasonal movements of its people. For young students Thomson’s story would be fascinating.

Likewise readers should have been told by Pascoe about the nomadic Aboriginals’ impressive skill in using fire, except in their creation of grassland. And yet fire was central to their way of life. It was vital for cooking, for warmth on cold nights, for illumination, for manufacturing many of their implements and weapons, and sometimes for hunting by day and fishing by night. Its smoke was used as a means of communication and also an insect repellent. One of the six chapters in Young Dark Emu is devoted to fire but nothing is imparted about its vital role in nomadic life.

History is a demanding profession, and we all make mistakes when interpreting it, especially in fields where new knowledge multiplies. Pascoe, however, might well be adjudged by some observers as accident-prone. Often readers will ask where he found this or that piece of evidence, but when they turn to the book which he names they will find, in nearby pages, evidence which contradicts his own narrative.

The debate about Indigenous history will go on and on, as the number of researchers increase. But one conclusion could be long-lasting. During the 40,000 years since those two symbolic deaths at Lake Mungo, their people generation after generation have shown remarkable resilience in the face of shocks and upheavals in Australia’s climate, land and seas.

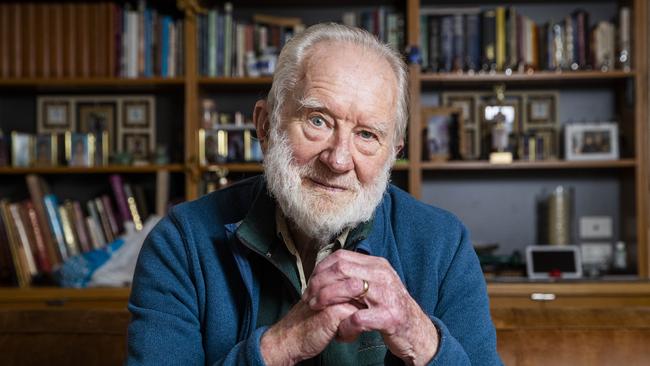

Geoffrey Blainey in 1975 wrote about Indigenous Australia in Triumph of the Nomads. An updated version, The Story of Australia’s People, came out in 2015.

A vital decision on our nation’s history is about to be made in Canberra. Should we bury in a secret place, without paying all respects, the human remains of two of the most symbolic people in Australia’s history? Or should we confer on them a more honourable burial in a known place and perhaps crown it with a monument?