Renewable superpower: Critical minerals are Australia’s ‘must have’ sovereign capability

Australia is rich in critical minerals needed to power the decarbonised future economy but it faces a raft of challenges in leveraging them.

There are many who think so, including the previous and current federal governments. The preface to the 2022 Critical Minerals Strategy declared the Morrison government “is taking action to grow Australia into a critical minerals powerhouse”.

Labor’s just released 2023-30 Critical Minerals Strategy expresses a similar sentiment, albeit with a greener tinge. Resources Minister Madeleine King says: “Australia can play a pivotal role in delivering the processed minerals the world needs for a clean energy future.”

Last month, the government entrenched clean energy powered by critical minerals as a third pillar of the US alliance in an unprecedented linking of climate change, energy, industry and national security policy.

The reasons for its optimism are not hard to discern. Our ancient land has always been geologically rich in minerals. For decades we have extracted them in large quantities, creating enormous wealth for every Australian and giving us an enviable standard of living. Even in today’s carbon-challenged world, coal, gas and oil continue to bring in a substantial share of export income.

But as the momentum towards clean energy passes the point of no return these are all diminishing assets. Critical minerals are on the rise because they will power the decarbonised future economy. They are already indispensable for the energy, transport, aerospace, medical, automotive and telecommunications sectors. Many are crucial for defence.

This gives them added value as strategic minerals because they are essential for modern weapons systems and their enablers.

Geoscience Australia defines critical minerals as “metals and non-metals that are considered vital for the economic wellbeing of the world’s major and emerging economies, yet whose supply may be at risk due to geological scarcity, geopolitical issues, trade policy or other factors”.

Countries differ on what constitutes a critical mineral. Silicon (used for engine blocks and thermal insulation) isn’t on the US list or zinc (critical to low-carbon and strategic technologies) on ours. Manganese (used for steel and military-grade alloys) is absent from the EU’s and India’s.

But more than 90 per cent of critical minerals appear on everyone’s list including all 17 rare earth elements. The problem is we don’t have enough of them in usable form. Lithium is representative. US energy officials forecast that the global supply of this mineral will need to increase 42-fold by 2050.

Viewed through the prism of investment it’s not immediately apparent why critical minerals, especially rare earths, are the subject of so much attention and concern. The critical minerals proportion of the $US35 trillion ($51.7 trillion) of investment that will be needed for successful energy transition to 2030 is $US360bn to $US450bn, according to the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook. The global rare earths market is a drop in the renewable energy bucket, although it is expected to rise from $US9bn to $US12bn by 2030.

However, market value does not capture their centrality to our lives – from the tactile hi-tech screens of our smartphones to the lithium that powers advanced batteries and the ultra-strong magnets that drive electronic vehicles and wind turbines.

It’s their unique physical and chemical qualities, when refined, that gives them their real value. Without access to critical minerals, economic development would be moribund, the rapid technological advances of recent decades would grind to a halt and militaries would be kneecapped.

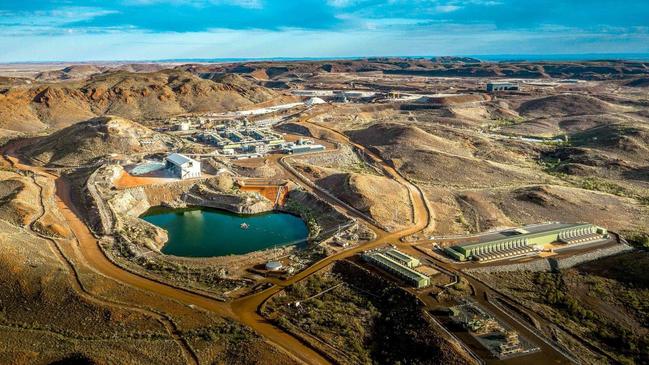

Australia’s growing prominence in the critical minerals sector is due to robust global demand; the perseverance of a handful of committed but under-resourced junior miners who produce half the world’s lithium and nearly 10 per cent of rare earths; and serendipity. Thanks to a random throw of the geological dice we have some of the largest recoverable deposits of cobalt, lithium, manganese, tungsten, vanadium and rare earths.

Labor says critical and other energy transition minerals could add $71.2bn to the economy by 2040 and $133.5bn if we process and make products from the minerals here, fuelling hope that Australia’s golden run as the quintessential “lucky country” will continue. But this rosy picture masks a raft of strategic, political and investment challenges. If unresolved, they threaten the third pillar of the US alliance and the Albanese government’s aspirations to make Australia a renewable energy leader.

The strategic problem for Australia and fellow democracies is the degree to which China has captured the critical minerals ecosystem, creating dependencies that can be leveraged for military and geopolitical advantage. This domination extends across the whole supply chain and is most evident in rare earths. As the critical minerals strategy makes clear, “concentrated critical minerals markets lead to volatile and fragile supply chains”.

The key to breaking this monopoly is to process critical minerals and develop downstream industries outside China – easier said than done. The Communist Party-state has built its near monopoly over decades and isn’t going to sit idly by while other countries develop competitive value chains.

Australia is one of the keys to weaning the world off its China dependency. Beijing knows this and will use its market power to crush competitors where it can, and seduce them when it can’t, by offering favourable financing, off-take agreements and cheap processing. The fact most of our critical minerals concentrate goes to China for processing – more than 90 per cent in the case of lithium – demonstrates the effectiveness of this approach. It’s also an indictment of our lack of vision and whole-of-government strategy.

It won’t be possible to build a world-class domestic industry and reduce our vulnerability to economic coercion unless China is excised from our critical minerals supply chain.

In November last year, Ottawa ordered three Chinese companies to divest their investments in Canadian critical minerals on national security grounds. In justifying the decision, Industry Minister Francois-Philippe Champagne said: “While Canada continues to welcome foreign direct investment, we will act decisively when investments threaten our national security and our critical minerals supply chains, both at home and abroad.” We should follow Canada’s lead.

The Albanese-Biden declaration of a climate change, clean energy and critical minerals third pillar is necessary to counter China’s domination of the sector by building comparable scale through trusted partnerships. The aim is to pull back China’s lead, reduce an unhealthy dependency and build sovereign capabilities in clean energy for economic and national security reasons.

If we play our cards right the Albanese-Biden agreement could become the foundational pillar of a wider global coalition of the willing drawing in Europe, India, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Southeast Asia, a process that has already begun. European officials are pushing the idea of a G7 “buyers club”. And the Biden administration is negotiating “minerals security partnerships” with 13 governments having already signed deals with Japan, Canada, Australia and Britain.

A key point of difference with China is the emphasis on high labour and environmental, social and governance standards. These contrast with the much lower standards that enable China’s state-supported companies to produce more quickly and cheaply than anyone else. We may not be able to compete with China on price but our best practice environmental, social and governance, Indigenous participation and labour standards are among our trump cards.

The EU is moving to legislate these standards, which means that given a choice, the EU will preference processed critical minerals and their products from countries such as Australia.

But we are still a long way from this nirvana. The third pillar rests on a Biden promise, not a legally binding agreement. This may not eventuate because of congressional opposition. The election of a Republican president, sceptical of climate change and the wisdom of committing American taxpayer dollars to foreign entities, is another potential fly in the ointment.

ESG could be a two-edged sword if it precludes partnerships with developing country suppliers that cannot yet meet Australian and US standards. Indonesia, the biggest nickel producer, wants to partner with Australia in processing and downstream capabilities. It also has floated the idea of a critical mineral’s producers club, modelled on OPEC.

Both make sense. A nickel partnership with Indonesia, buttressed by common membership of a producers club, would add much needed economic weight to the relationship and advance our regional security interests. But it won’t happen unless we cut a deal to allow time for Indonesia to raise its ESG and labour standards.

Collaboration between the wealthier democracies might be dampened for a different reason: they are also commercial competitors. “It is a partnership, but it’s a partnership with certain levels of tension” says Kirsten Hillman, Canada’s ambassador to the US, in an interview for The New York Times. “It’s a complicated economic geopolitical moment.”

Another concern is that the amount of money available for US investment in the Australian critical minerals and clean energy sector may be less than meets the eye.

Giving Australian resource companies domestic supplier status under the $US369bn Inflation Reduction Act isn’t likely to be the bonanza that some anticipate. In practice, our miners may gain access to only part of a $US500m manufacturing fund. It’s doubtful the US will fund critical minerals processing here.

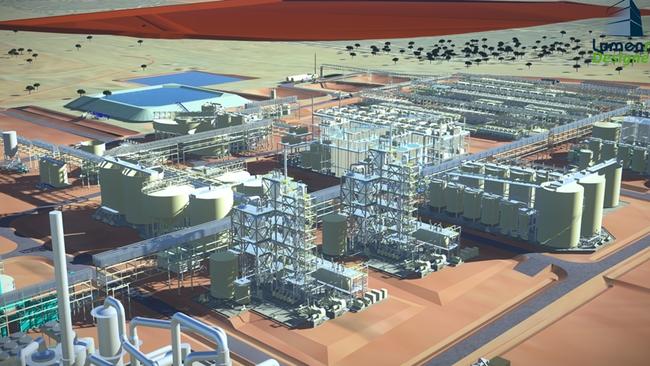

Processing in Australia is the key to realising our potential as a global renewable energy player. If the ore is only mined here and then sent to the US instead of China for processing, we risk becoming a quarry once more rather than a renewable energy superpower.

Avoiding this problem will require a substantial scaling up of investment in the sector. Because of their small size, the cash-strapped junior miners who produce most of our critical minerals struggle to fund their enterprises. If forced to divest, China’s money will have to be replaced by domestic or trusted foreign investment. Otherwise, our critical minerals sector won’t survive.

Processing plants are expensive and take time to build. Banks and other major lenders are unwilling to fund them because of the perceived risk. Recognising this, both the Coalition and Labor have established facilities to seed and support the critical minerals sector.

But they are fragmented, the mandates are too risk averse and the available capital falls well short of what is required despite the 2023 strategy’s commendable initiative to direct an additional $500m of capital towards the sector.

Given the vast subsidies and tax incentives directed towards renewables in China, the US and Europe and the trend towards the nationalisation of critical minerals in developing producer countries, such as Chile, Bolivia and Mexico we need to rethink our critical minerals financial architecture. It’s simply not fit for purpose.

A necessary first step is to discard the discredited “dig and ship” culture that cruelled attempts to add value during previous mineral booms.

The 2023 strategy talks enthusiastically about crowding in commercial finance. But commercial investors with deep pockets are still sitting on the fence waiting for the government to put in place the necessary incentives to make critical minerals a less risky, more enticing investment proposition.

The only way to get them off the fence is to ignore the advice of market purists and establish a system of tax incentives, differentiated royalties, targeted subsidies and export assistance packages that levels the playing field. And it requires the government to decide how far down the critical minerals value chain Australia should go and how best to attract the billions of dollars of investment from capital markets, an issue for the wider mining sector.

In remarks to the Queensland Resources Council last month, mining magnate Gina Rinehart said: “We’re simply not seeing the massive investments you would expect given high commodity prices, and despite the stated need for rapid expansion in metals and minerals able to meet the government’s green policies.”

Rinehart estimates that there is a $60bn mining investment gap that, unless filled, will be “a missed opportunity for Australia”.

Exploration is also underdone. Talking up our minerals endowment is all very well. But the reality is that 80 per cent of the continent is geologically unexplored or under-explored, including our sea-bed resources that contain rich deposits of manganese, cobalt, nickel, gold, silver, copper and a wide range of rare earths.

The “extraction of deep seabed mining resources on an industrial scale at incredible depths is a new frontier” with “immense” potential gains, Anthony Bergin and Maurice Brownjohn wrote in this newspaper on Monday.

Exploration has fallen away because of dangerously low levels of investment, excessive red tape and a green zeitgeist that regards all mining with suspicion. We lack a high-quality geological survey of all land and sea-based mineral resources to inform commercial mining. We have only a handful of productive mines and no strategic stockpiles of critical minerals to help buffer the country in times of need.

These constraints must be dealt with head-on as the government finetunes its strategy and determines critical minerals funding priorities. It must incentivise exploration, processing and downstream manufacturing; reduce green and red tape; establish strategic stockpiles; and strengthen mining’s social licence by pointing out what should be obvious to environmental activists. No energy system is pristine, including one based on renewables.

The green revolution won’t be possible without critical minerals mined and processed in Australia. The alternative is an industry dominated by autocracies with scant regard for the environment or any real commitment to human rights, Indigenous participation and high labour standards.

Asking King to do all this is beyond her department’s remit. If the Prime Minister wants Australia to be a renewable energy superpower he should elevate the development of the still nascent sector in the government’s priorities. Critical minerals are a “must have” sovereign capability. They are vital to our economic prosperity and national security. Decarbonising the world’s energy system to mitigate the worst effects of climate change won’t be possible without them.

Alan Dupont is chief executive of geopolitical risk consultancy the Cognoscenti Group and a nonresident fellow at the Lowy Institute.

Rarely does a sparsely populated middle power get to play a leading role on the global stage. But could the continent’s rich critical minerals endowment make Australia a renewable energy superpower and rules maker in a world beset by geopolitical rivalry and the intertwined challenges of energy transition and climate change?