Regretful former slave trade captain wrote Amazing Grace

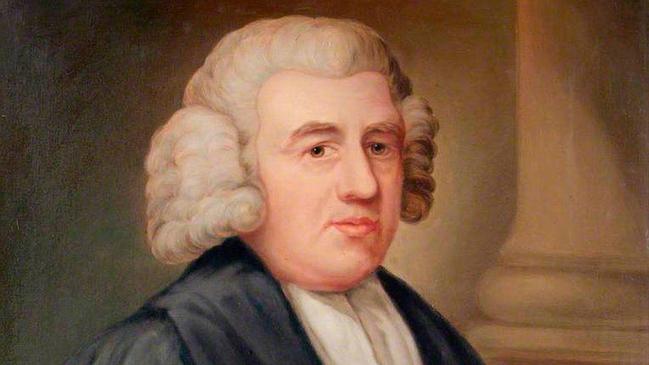

Slave trade ship’s captain-turned Anglican cleric John Newton wrote a sermon 250 years ago that, put to music, became Amazing Grace.

John Newton travelled a great distance in a long life. He first went to sea aged seven in 1732 with his shipmaster father who sailed the Mediterranean. Pressed into service for the Royal Navy, he saw India and Africa, and became active in the slave trade.

He once tried to desert a ship and was punished with 96 lashes and surprised himself by thoughts about murdering the captain. Later, his carefree acceptance of the cruelty of slave trading waned. Guilt led to good, and Norton’s longest journey – to seek redemption – began.

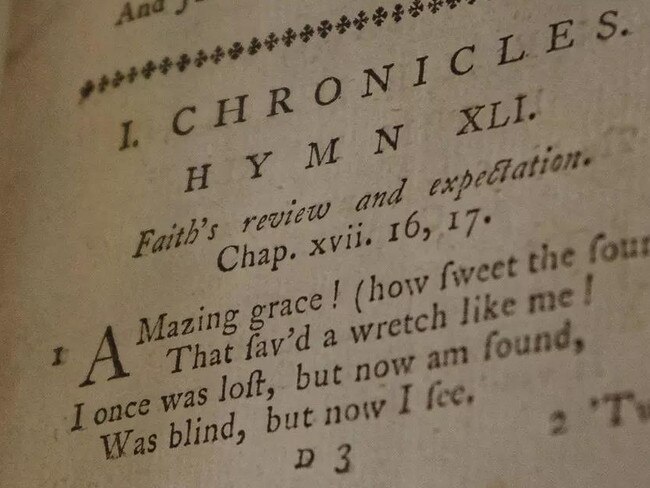

He studied for the priesthood and, 250 years ago this week, on Friday, January 1, 1773, the congregation of St Peter and St Paul Church in Olney, a lace-making village 95km north of London, first heard words we now all know.

It was a sermon long in the works. It would become one of the world’s most readily identified hymns. At the pulpit and looking down on handwritten notes, Newton uttered: “Amazing grace, how sweet the sound that saved a wretch like me. I once was lost, but now I’m found, was blind but now I see.”

The 47-year-old curate had worked on this for two years, but the theme stemmed from 19 years before, when he suffered a stroke after completing the third and final voyage servicing the so-called Triangle Trade – and deciding that slavery was evil.

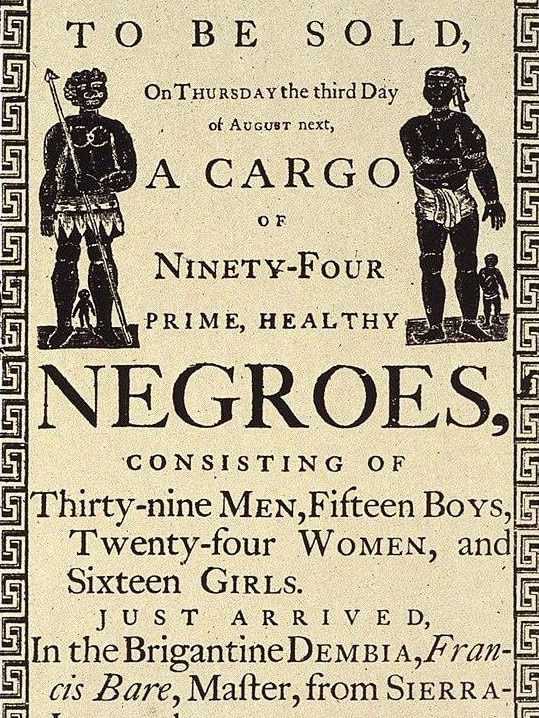

The Triangle Trade comprised three-way trips from Britain that took clothing, fabrics, tools and other goods to what would become known as the Slave Coast encompassing the modern West African republics of Senegal, The Gambia and Sierra Leone as far south as Angola.

Their harvest of slaves – paid for in a complex business that involved Africans, but the demand came from Arabs and Europeans – was delivered mostly to the Americas, including Brazil, North America, the West Indies, particularly the Bahamas, and Bermuda.

Along the American east coast slave traders would pick up cotton, sugar, molasses, rice, tobacco, wood, whale oil and furs, and head home.

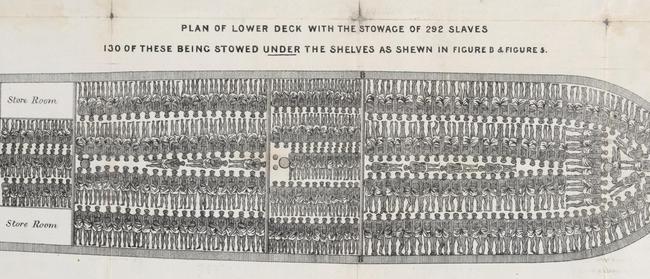

The collection of the doomed humans and their transport to where their labour was in demand was on an industrial scale not unlike that employed by the Nazis at Auschwitz and Treblinka during the Holocaust.

Perhaps more than 12 million Africans were abducted as part of the Atlantic slave trade, many of them dying during the gruelling, dehumanising passage.

As an indication of their number, by 1750 there were 65,000 African slaves on Barbados – it is only half the size of Tasmania’s King Island – working the sugar plantations. They easily outnumbered the 18,000 white settlers enslaved by greed; the uncontested god of profits from the plantations was free labour.

Evidence given later at a British inquiry into the trade – never approved by any legislation there – described their transport conditions. They were chained by arms and legs in pairs and laid side by side in cramped “decks” – but of about a metre or so clearance. None could stand. There were large buckets at each end and when freed briefly from the irons they might crawl off to deal with their endless seasickness.

Almost a third might die of from dysentery, scurvy and the dehydration caused by seasickness.

It was hot and humid and in rough seas the portholes – their only source of fresh air – would be covered.

As soon as they arrived in strange lands, they were sold and put to work across long days; avoiding punishment and the hope of food their sole incentives. Dental records from slave graves indicate they died on average shy of 30. The same records indicated not just inadequate diet but periods of malnutrition, even starvation. The short lives of slaves only fed the beast of a trade.

An English doctor, Alexander Falconbridge, joined four slave voyages over five years from 1782 and was well paid to supervise the welfare of the distraught human cargo.

On one journey they held 609 tormented captives. On top of his salary he was paid one shilling for each African he delivered alive at their destination. Back home he had been conditioned to accept the trade: “Previous to my being in this employ I entertained a belief, as many others have done, that the kings and principal men bred negroes for sale as we do cattle.”

But a few journeys in, he had seen enough.

“The deck, that is the floor of their rooms, was so covered with the blood and mucus that it resembled a slaughterhouse. It is not in the power of the human imagination to picture a situation more dreadful or disgusting. Numbers of the slaves having fainted they were carried upon deck where several of them died and the rest with great difficulty were restored. It had nearly proved fatal to me also.”

By the time Falconbridge wrote An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa, Newton’s protests about slavery were gaining momentum, even if, in England at least, Amazing Grace remained an obscure Anglican hymn (its original title, Faith’s Review and Expectation, hardly helped).

Falconbridge became friends with Newton, now an evangelical Christian seeking to make amends for his earlier life during which he abandoned all faith. One day, Newton met a brilliant young Yorkshiremen, William Wilberforce, who similarly had led an active life of drinking and gambling and whose family, coincidentally, had generated great wealth from refining sugar imported from the West Indies. Wilberforce had been elected to the House of Commons aged 21 and still a student at Cambridge University. At university he formed a lifelong friendship with William Pitt, who would twice be prime minister.

The Quakers had long opposed slavery, but they lacked the influence of the Anglicans. The abolitionist conviction gained strength and Pitt was onside convincing his friend, who sat as an independent, to prepare a motion to outlaw slavery. This brought together those hostile to slavery. Wilberforce gave a series of speeches condemning the trade, but in a Commons afraid of radicals – the French Revolution was in full flight – his parliamentary bill was easily defeated.

But his persistence, despite frail health, slowly paid off and Pitt introduced a Motion for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1792, with the words: “We may now consider this trade as having received its condemnation; that its sentence is sealed; that this curse of mankind is seen by the House in its true light; and that the greatest stigma on our national character which ever yet existed, is about to be removed!”

To ensure some result, a compromise was agreed that slavery be slowly phased out, and this was passed.

Falconbridge died that year. By 1807, Wilberforce, assisted by Newton and others, had swung public opinion, and that year’s Slave Trade Act passed by 283 votes to 16. Pitt had died weeks before. Newton would die months later.

Meanwhile, Amazing Grace was assuming a new life in the US. A Christian revivalist movement took hold at the start of the 19th century preaching that everyone was equal. Freed slaves joined and many became ministers, sometimes preaching to white congregations. The underpinnings of the reform movement were in place.

These new church services were much less formal and involved communal singing and shouty sermons about avoiding sin and seeking forgiveness – fertile soil for Amazing Grace, which was married to music (from the folk tune New Britain) by American composer William Walker in 1835.

In any case, the Amazing Grace lyrics were being sung to other, lesser-known tunes picked up locally.

The issue of slavery drove four bloody years of America’s civil war. It was as if Newton’s words had been written for them. On the Union victory, the last Confederate slave was freed on June 19, 1865. It became known colloquially as Juneteenth. President Joe Biden signed a bill officially recognising the day in 2021.

The Civil Rights Bill was enacted a century after the war, but equality still eludes many black Americans.

A dozen years after the civil war, Thomas Edison invented the phonograph, and, finally, Amazing Grace made it to record, by the Original Sacred Heart Choir. A thousand versions have followed, unifying the music and the words, and introducing them to secular audiences.

It has twice been a million-seller – with Judy Collins in 1970 and as an instrumental by the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards two years later, which, by 1977, had sold seven million copies. It has been recorded by Glen Campbell, Rod Stewart, the Neville Brothers, Mahalia Jackson, Blind Willie McTell, Jessye Norman, Elvis Presley, Charlie Rich, the Spinners and even Meryl Streep.

On April 4, 2015, white North Charleston police officer Michael Slager shot dead black man Walter Scott after pulling him over for having a faulty brake light. Scott had a warrant for his arrest on another matter. He fled across a park and in notorious footage was shot eight times without warning. The officer was convicted of second-degree murder and jailed for 20 years. Scott’s mother and brother said their faith in god gave them the ability to forgive Slager.

That April 14, South Carolina senator Clementa Pinckney, the youngest black man to be elected in that state – some believed he might one day be president – emotionally pleaded with his colleagues that police be fitted with body cameras.

On June 17, white supremacist Dylann Roof shot Pinckney and eight others dead in a church Bible study class.

At Pinckney’s funeral, president Barack Obama gave the eulogy but stopped, overwhelmed by the sadness and waste, and twice spoke the words “amazing grace”. His mellow baritone then intoned the five notes that make up those words and the audience rose as one to complete Newton’s 1773 sermon.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout