Radical new Chinese era signals years of living dangerously

Australians need to absorb a disturbing message — the scale of foreign intelligence activity against us today is greater than it was during the Cold War.

As the Year of the Pig runs out, we will soon confront the Year of the Rat, and perhaps the year of living dangerously for Australia-China relations.

The blizzard of controversies, allegations, misunderstandings and plain hard disagreements bedevilling the Canberra-Beijing dynamic has served a salutary purpose for our politics and society. It has rudely announced a new era in Australia-China relations, and therefore a new era in politics, foreign policy and strategic outlook.

Spies, lies, influence and interference, democracy and demonstrations, human rights in Xinjiang, astonishing election results in Hong Kong — we are passing through a swirling season of coming to grips with reality.

Tony Abbott expressed it with the greatest clarity in his best speech since leaving the prime ministership. He told the Lowy Institute: “When your biggest trading partner is also a big strategic challenge, living with trouble has to be taken for granted — unless you change your economy or change your polity, neither of which should happen.”

Within Australia, we saw extraordinary allegations that figures acting on behalf of Beijing tried to bankroll a candidacy for parliament. We also saw an alleged Chinese intelligence officer defect. Both claims must be treated with great caution.

Two federal Liberal MPs, Andrew Hastie and James Paterson, were denied visas to visit China after being invited on a delegation of politicians. The Chinese embassy insisted they “repent” for their heretical views before being allowed to enter the Middle Kingdom.

Internationally, a vast trove of Chinese government secret documents were leaked to The New York Times, which demonstrated a savage determination by Beijing to suppress Uighur religious and political sensibilities and to assert absolute control, not least through mass incarceration.

The documents also disclosed that some Chinese officials were deeply reluctant to carry out these orders. What does the leaking itself imply?

One of Australia’s most gifted Sinologists, Geremie Barme, formerly of the Australian National University, believes the documents are genuine because no one could imitate and sustain quite the fractured tone of the Chinese communist bureaucratic state.

In Hong Kong, the only part of communist China that gets to vote on anything, after six months of pro-democracy demonstrations it was assumed the public had grown weary of the disturbances.

They have cost Hong Kong economically. In recent weeks some of the demonstrators have engaged in ugly violence. Yet elections for district councils saw pro-democracy, anti-Beijing candidates achieve a landslide of staggering proportions. They won nearly 90 per cent of the seats and 18 of 19 councils in an election that had a record turnout — 71 per cent — for any election ever held in Hong Kong.

US President Donald Trump signed the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act into law. This provides for annual US assessments of freedom in Hong Kong and harsh sanctions if that freedom is abridged. Hong Kong citizens waved and sang to Trump’s portrait. Beijing reacted with fury.

At home, we have had a deluge of powerful institutional warnings about Beijing’s activities. Duncan Lewis, the recently retired head of ASIO, said Beijing was using interference techniques to try to control Australian politics, and that the threat was long-term.

In an earlier ASIO annual report, he had written: “With the terrorist threat showing no signs of significantly decreasing, ASIO has limited scope to redirect internal resources to address the increasing demand for our counter-espionage and foreign interference advice.” More dramatically, Lewis said foreign interference was a greater existential threat to Australia than terrorism and “the current scale of foreign intelligence activity against Australian interests is unprecedented”.

That word unprecedented is freighted with significance. The scale of foreign intelligence activity against Australia today is greater than it was during the Cold War.

Australians need to absorb that disturbing message.

It was reinforced from multiple points of Australia’s most important institutions. Nick Warner, director-general of the Office of National Intelligence, told a Senate estimates committee that he broadly endorsed Lewis’s assessments.

Frances Adamson, head of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, had previously told estimates a degree of ongoing conflict with Beijing was “the new normal”.

Dennis Richardson, also a former boss of ASIO, and former head of the Department of Defence and DFAT, in reflecting on the angst with Beijing, told The Weekend Australian: “At the base of it is China’s own actions. We would not be having this debate if it were not for China’s actions both in Australia and overseas. In part it is their tendency to hack into everything that moves in Australia.”

Richardson, Warner, Lewis and Adamson are not swivel-eyed, right-wing loons — Richardson was Bob Hawke’s chief of staff. Their statements, and many others, represent the mature conclusions of the deepest work and analysis of national policy institutions.

These statements alert and educate the Australian public, as do the words and actions of the federal government and opposition. The Coalition government passed foreign interference legislation with Labor’s support.

Both sides of politics agreed that Huawei should be kept out of the 5G network on national security grounds. Both sides support the increased national security dimension of Foreign Investment Review Board scrutiny of foreign acquisitions of critical infrastructure and other assets.

Yet it is still difficult, understandably, for Australians to adjust to the new paradigm, and how radically different it is from the old. From 1972 to 2014, the Australia-China relationship was like a market stock that trended ever upwards. There were ups and downs along the way, but the chart of the stock, the band in which it moved, trended ever upwards. This era began when Gough Whitlam extended diplomatic recognition to the People’s Republic of China.

And it ended in 2014 when Abbott hosted China’s President, Xi Jinping. On that visit, Xi embraced a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership between Beijing and Canberra. During Abbott’s tenure the two nations also negotiated and finalised a wide-ranging free-trade agreement.

This was both the high point and the last moment of the old paradigm. It is also an irony that of all prime ministers since John Howard, Abbott had the most success with the Chinese. Abbott has probably spent more time with Xi than any other Australian, visiting China as Xi’s guest, hosting Xi in Australia, and holding bilateral talks with him at regional summits.

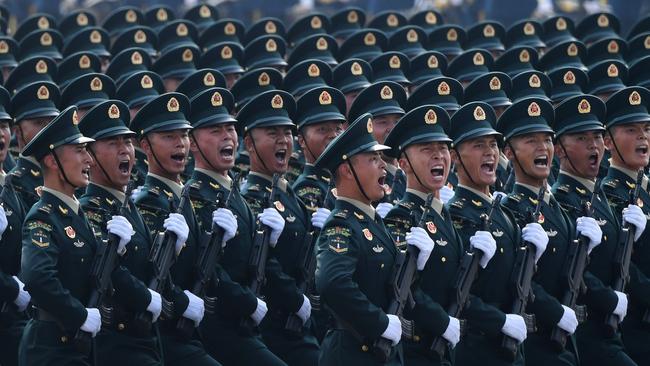

Since then, Xi has changed Chinese political culture fundamentally. His government has crushed all internal dissent, suppressed religious minorities, arrested all the human rights lawyers, occupied and militarised the South China Sea, forged a dangerous strategic relationship with Moscow, interfered in the domestic politics of numerous nations, incarcerated foreign individuals as bargaining chips in bilateral disputes, and aggressively engaged in cyber and other espionage at a level beyond that of other nations. These actions are where the big change lies.

Abbott’s Lowy Institute speech is more use to Australia as a guide today than Kevin Rudd’s weighty analysis or Paul Keating’s pretty wordscapes. Rudd’s analysis is always valuable but he, too, conveniently blames Trump for the disruption to the Beijing-Washington accord, whereas the fundamental change is that which Xi has brought to the political, strategic, economic and social arc of Chinese development.

Keating was an immensely successful foreign policy prime minister but he now deals with a fantasy China that exists only in his imagination. How else to explain his extraordinary claim that the Beijing government is not motivated by ideology? To reach this bizarre conclusion it is necessary to ignore every significant speech and statement of Xi himself, and all the guiding documents of the Chinese Communist Party. Even the Chinese, according to the Great Helmsman, don’t understand modern China because it doesn’t fit into the Keating policy playbook, in which it is forever 1993.

Abbott, like Howard, eschews intellectualisms for their own sake and shuns Latinate phrasing. He writes more like George Orwell. He attacks a problem directly, always the best way. His Lowy speech features sharp analysis — “It’s worth noting that the Chinese have not become our biggest customer because they wanted to do us a favour” — and concrete policy recommendations, such as: get closer to India, build a bigger defence force and do it quickly, be positive with Beijing where you can, don’t generalise about the Chinese diaspora in Australia, don’t compromise core national interests.

Scott Morrison will visit India and Japan early in the new year. These are immensely important relationships in their own right. But the role of Tokyo and New Delhi is also critical to maintaining a sensible balance in a region that Beijing wants to dominate. The Prime Minister is rightly ambitious for both relationships.

The development of the Quadrilateral Dialogue — involving the US, Japan, India and Australia — is one of many important developments. That the Quad recently held its first meeting at foreign minister level is encouraging. The decision by Rudd and his then foreign minister, Stephen Smith, to unilaterally kill the Quad in 2008, to please Beijing, was one of the most foolish and counter-productive foreign policy moves of any modern Australian government. It did immense harm to the Canberra-New Delhi relationship. It was a decision that had to be reversed and the Quad now enjoys bipartisan support in Australia.

Nonetheless, the past few weeks have shown the difficulty in some sectors in coming to grips with the new era in Australia-China relations. This was most evident with Keating, but you see it, too, in many of the pro-Beijing voices, such as former ambassador Geoff Raby and in the political naivety of some business leaders.

But even sucking up to Beijing does not guarantee calm sailing. No businessman could have done more to cultivate good relations with mainland Chinese leadership than James Packer, yet no Australian business was ultimately treated more cruelly.

Peter Varghese, former head of DFAT and the most sophisticated of our foreign policy thinkers, believes the relationship has changed profoundly since 2014. He tells The Weekend Australian: “We will see a bifurcation of the relationship into economic and non-economic parts. The economic will be positive. But the rate of growth will slow. The non-economic will be very truncated. We are beginning to recognise that our strategic congruence is limited. China’s fundamental strategic positioning is not consistent with our interests.

“There is still a view among some that there’s a problem in the relationship and Australia has to fix it. But most of the problems we have arise from the nature of the Chinese political system.”

This does not mean, Varghese says, that we see China as the enemy. But there will be political and strategic competition as well as economic co-operation.

Barme has long understood there was an unavoidable contradiction between the political culture of the Chinese Communist Party and that of democracies such as Australia. He says official Chinese policy under Xi uniquely combines the Stalin/Mao experience of politics with the revanchism of China and Chinese nationalism over the past century.

He argues that those Western liberals who over the past 30 years hoped for a gradual liberalisation of China’s polity were not irrational. There was some reform of the legal system, some widening of space for the media, and the Westerners reflected the hopes of Chinese liberals to whom they often spoke. But “I was never a believer in that (liberalisation)”, Barme says, “because unless you changed some fundamentals it could all be overturned in a moment. Xi has shut down all internal debate and made many rigid proclamations. He’s created a sort of brittle autocracy. Historically such dictatorships don’t do too well. And what is delightful is they’ve come up against such a mercurial, unpredictable, Mao-like figure in Donald Trump, who drives them mad.”

Australia has not lost the formula for good relations with Beijing. It’s just the formula doesn’t work any more in a new and different environment. It’s not paradigm lost; it’s reality changed. This past few weeks, we’ve come some distance in catching up with reality.

Now we enter the era of living dangerously.

NOTE: The Press Council has partially upheld a complaint about this article. Read the full adjudication here.