Radical changes under Trump reinforce Australia’s need for more defence self-reliance

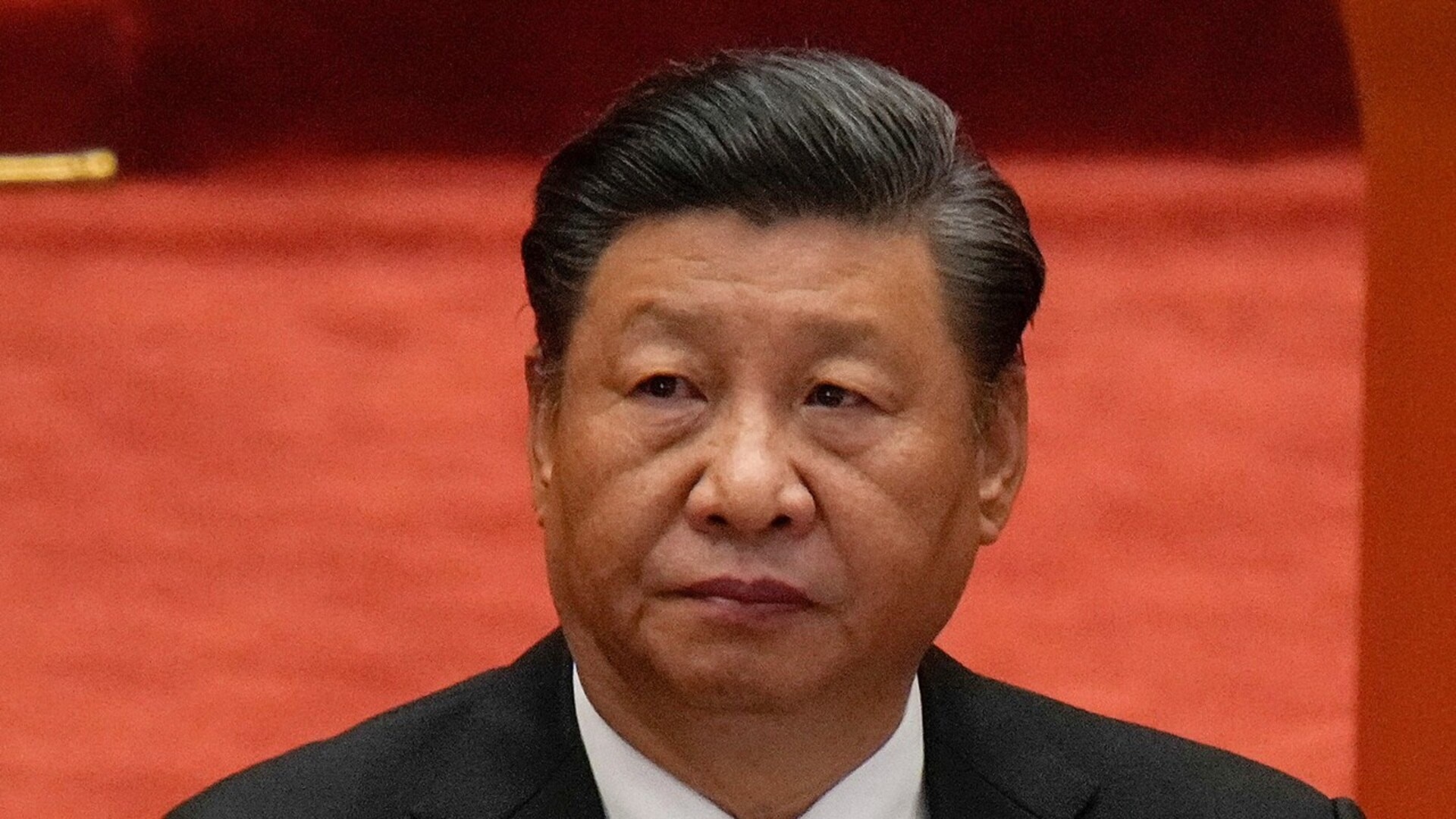

How best to position Australia’s national defence effort to respond to China as a potential adversary and – in a different way – the US, presumably still as an ally.

Two recent foreign challenges suggest Australia urgently needs to increase its defence self-reliance and to ensure the increased funding this would require is available. Defence spending now requires urgent review.

First, the circumnavigation of our continent by three Chinese warships puts in question our capacity to keep even just one flotilla in February and March under persistent surveillance. To do this, we need to re-examine our intelligence and surveillance capabilities. We knew well enough where the Chinese warships were but not what they were doing.

Second, the aggressive behaviour towards Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky by US President Donald Trump in the White House on February 28 raises the question of our need for a higher degree of defence self-reliance.

This does not mean abandoning or jettisoning the alliance with the US. But it does mean we need better ability to manage military contingencies in our strategic approaches without depending on the US. This will demand greater capabilities in longer-range weapons and supporting intelligence, surveillance, and tracking. These contingencies raise the need for a significantly greater degree of defence self-reliance. The US under Trump will expect us to manage them by ourselves.

Further, the principle of extended deterrence – under which the US remains the strategic guarantor for its Asia-Pacific allies, especially against nuclear attack – has not (yet) been challenged by Trump or his senior administration officials. That guarantee seems a curious exception to Trump’s transactional approach to other security commitments.

However, short of nuclear war, we need to ascertain whether our strongest ally has transformed overnight into our most immediate problem. Already we see that Russia’s longstanding ambition to divide the NATO alliance is several steps closer. The assumption still reigns in Australia that such threats are something that happen to other people, a long way away, and will never come to our homeland. With that belief, we have indulged ourselves in the luxury of merely incremental increases to defence budgets, rather than the transformative investment that now is needed.

Such transformation is required to ensure, first, that the Australian Defence Force can surge to meet the demands of new short-warning contingencies and sustain the associated rates of effort; and, second, that the ADF can continue to be the basis for further military expansion in the event that our strategic circumstances deteriorate further.

We need to understand that the US is undergoing radical change under Trump. As King’s College London emeritus professor of war studies Sir Lawrence Freedman observes, “The US is shrinking before our eyes as a serious and competent power.”

Taken together, these observations reinforce Australia’s need for a greater level of self-reliance.

These new issues are demanding because of their severe and sudden impact on our strategic environment. They require the Defence Organisation to revisit its allocation of resources for foreseeable military operations.

There needs to be a review of operational requirements for anti-ship missiles, drones and associated ammunition, sea mines and uncrewed underwater vehicle, and air-to-air and air-to-ground missiles.

This must result in a new allocation of resources to this demanding endeavour. It must be plainly understood this is what is required in any robust re-examination of demanding new military operations and their funding.

In the past few years it has become trendy for defence experts in Australia to assert that we need to spend 3 per cent to 4 per cent of our GDP on defence, compared with barely 2 per cent of GDP at present. That would mean finding an additional $28bn to $55bn a year and bringing the overall defence budget to $83bn to $110bn a year, compared with $55bn now.

On March 7, US under secretary of defence for policy nominee Elbridge Colby bluntly called for Australia to spend 3 per cent of GDP on defence. Making such arbitrary claims for an additional $28bn a year is not a responsible approach to defence planning. Instead, what is needed is a much finer-grained definition of the ADF’s need for enhanced missile strike capabilities and their associated deterrence.

Australia’s Defence Organisation needs to get on with this as a matter of urgency. Our focus now needs to be not so much on additional highly expensive major platforms such as ships and crewed aircraft but giving new priority to surveillance and targeting capabilities, missiles and ammunition, and uncrewed systems.

Such an approach would be much less expensive and much timelier than the acquisition of new major crewed platforms.

The fact remains that today’s ADF, together with supporting capabilities, has little ability to sustain operations beyond low-level contingencies.

Moreover, assumptions about force expansion made across many previous decades are no longer appropriate, particularly with respect to major platforms.

In contrast, the government’s 2024 Guided Weapons and Explosive Ordnance Plan presents us with a way ahead. This involves significantly increasing the ADF’s ability to sustain high-technology operations and giving a credible path for powerful force expansion based on modern long-range precision strike and targeting – which is far quicker and much cheaper.

At present, Defence is investing $28bn to $35bn to develop and enhance targeting and long-range strike capabilities out to 2034. These capabilities provide the ADF with a greater capacity to hold at risk a potential adversary’s forces that could target Australia’s interests during a conflict. But this is just the beginning. There are more expensive investments to be made; for example, in integrated air and missile defence.

And the 2024 plan is wrong to imply that our geography is dead: rather, the way we must use it has changed. The idea of steadily building up an incremental capability regarding long-range strike missiles – including their manufacture in Australia – is much more important in our current circumstances than buying more hugely expensive jet fighters or submarines.

Merely asserting that a particular percentage of GDP is appropriate for the defence budget is not adequate. Arguments that say only “more is better” will get us nowhere. Defence needs a story to tell – a conceptual framework, agreed and accepted by government and by the machinery of government, as the basis for considering more specific issues and initiatives. It must be suitable for public presentation, not only to get public understanding of the need for increased funding but also potentially to get acceptance of the need for a new capacity to handle what looks like an extremely worrying emerging strategic situation in the shorter term.

The issues to be confronted include the level of strategic risk the government is prepared to accept.

What options in this respect does it want to consider? Where does the government sit in the new strategic environment on sovereignty and self-reliance? What range of options should Australia develop for contributing to US-led operations in the Indo-Pacific? This will need to be a wider choice than in the Cold War, when the primary locus was Europe and the North Atlantic rather than Asia. And what would be the right level of reliance on the Trump government for intelligence and operational/combat support, and logistics support?

Further, Australia needs to consider its options for working more closely with other countries in the region, such as Japan, especially in the event that the US reduces its commitment to the area.

In many ways, the key point is how best to position Australia’s national defence effort (not just the ADF) to be able to surge in response to short-warning contingencies involving China as a potential adversary and – in a different way – the US, presumably still as an ally. The short-warning contingencies of today’s strategic circumstances will be potentially much more demanding than those of earlier years.

The legacy of the previous five decades of extended warning time is, in effect, an ADF with little capacity today for sustained military operations, especially at an intense level. So, positioning Defence to have this surge capacity requires close attention. It is good that governments have, progressively, recognised most of these issues. But implementation has been slow.

The end of the era of extended warning was made clear in the 2016 defence white paper, drafted in 2015. This was 10 years ago, the length of time during which previous defence policies assumed we would respond to strategic deterioration and expand the ADF. But in terms of more potent defence capabilities, we have very little to show for it.

Even so, Defence’s adoption of net assessments (modelling likely enemy capabilities against ours, including both sides’ logistics support) is a powerful tool contributing to decisions about the force structure, preparedness and strategic risk. Decisions on communications, surveillance and targeting capabilities reflect the importance of Australian sovereignty in these vital areas.

Defence is grasping the opportunities presented by the new technologies of remotely operated uncrewed platforms (combat aircraft, underwater vehicles and some larger surface warships). Such platforms offer a more expeditious and less expensive mode of force expansion than the acquisition of major crewed platforms. Much the same can be said of the programs to acquire and build in Australia a range of modern long-range precision strike missiles.

The matters set out above would contribute to the basis for estimating the costs of defence policies, including the costs of different policy options such as different levels of self-reliance and strategic risk; more or fewer options for contributing to US-led Indo-Pacific operations; and greater or lesser reliance on the US for sustainability stocks of spare parts and munitions during contingencies.

Other factors include the need to address workforce issues, including the difficulties that the ADF has in attracting and retaining its personnel. If the latter difficulties persist, there may well be a need to consider radically different approaches to the ADF workforce, including some form of national service, an increased focus on the reserves or both.

Arguments for increased funding based on the above analysis would be much likelier to carry the day than mere assertions that a particular hypothetical fraction of GDP should be the target for the defence budget.

Finally, we are of the view that Defence’s decision-making abilities are not adequate, even for peacetime governance.

It is, therefore, but a short step to be concerned that the arrangements for decision-making in the event of the more serious contingencies that now have to be part of the defence planning basis would be even less adequate. This needs attention.

Paul Dibb and Richard Brabin-Smith are professors of strategic studies at the Australian National University. They were both deputy secretaries in the Department of Defence.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout