Queensland could be Anthony Albanese’s rescue or ruin

It’s Peter Dutton’s stronghold and the state that delivered Scott Morrison’s ‘miracle’ 2019 victory. Labor holds just five of the 30 federal seats, and clawing back ground is a hard ask.

For Anthony Albanese, Queensland could be his rescue or ruin. The failed voice referendum and concern about cost of living have Labor down in the polls and desperate to retain government at the next election, due by May next year.

It would be a big call to predict Labor, which won office with just 32.6 per cent of the primary vote nationwide, would lose after a single term. A first-term government hasn’t lost a re-election bid since 1931.

But with Labor holding a slim two-seat majority, ALP strategists are already jittery about the possibility of going into minority government. Labor is bracing for losses in Western Australia, which delivered an extra four seats in 2022, with other key seats in NSW and Victoria also considered at risk.

So where better to claw back ground than in Queensland – Peter Dutton’s stronghold and the state that delivered Scott Morrison’s “miracle” 2019 victory – where Labor holds just five of the 30 federal seats?

It’s a hard ask. Despite Labor holding power at a state level for 28 of the past 35 years, it seems Queensland voters have not been so enamoured by the party’s federal counterpart.

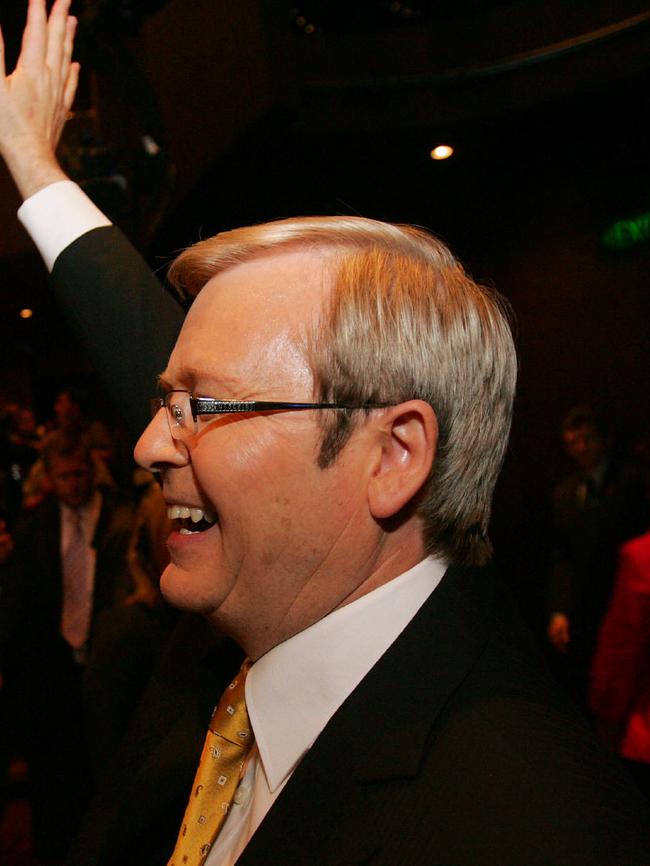

The Coalition has won a majority of seats in Queensland at 19 of the past 25 federal elections. Kevin Rudd, who never stopped reminding people where he was from (“My name’s Kevin, I’m from Queensland and I’m here to help”), was the last Labor leader to pull it off. The triumph lasted only one term.

Bob Hawke, whose knockabout character appealed to Queenslanders, set the high-water mark in 1990, winning 15 of the state’s then-24 seats.

But since the 2007 “Ruddslide”, Labor has lost 10 of the 15 Queensland electorates it held including the key regional seats of Dawson, Flynn and Capricornia (all now held by Nationals), and Leichhardt (held by a Liberal).

And Labor is still flat-footed in Queensland, with last month’s Newspoll showing its primary vote remains on the floor at 27 per cent – unchanged from election night in 2022 – seven points below the party’s national primary of 34 per cent.

Knowing how important Queensland is, Albanese spent a lot of time in the Sunshine State ahead of the 2022 poll, trying to win back the voters who turned on Bill Shorten and handed Morrison his come-from-behind win in 2019.

Morrison was so successful in Queensland because people liked him. Nine months before his surprise election win, he had rolled Malcolm Turnbull in the wake of the disastrous Longman by-election. The loss in Longman, on Brisbane’s outer north, demonstrated Turnbull’s unpopularity in Queensland and guaranteed his knifing.

Shorten was not well liked in Queensland either after he tried to sell a big reform agenda that included hitting the hip pockets of retirees, a dominant demographic in many election-deciding seats in the state.

Under Shorten, Labor’s primary vote in Queensland collapsed to 26.68 per cent and left the ALP with a single Senate spot in its worst upper house result since 1949.

As opposition leader, Albanese went on a charm offensive, visiting Queensland more than any other state in the lead-up to and during the 2022 campaign.

It didn’t work. Labor’s representation went backwards, losing the seat of Griffith to the Greens. Labor miraculously made it to a majority despite the lowest proportion of federal seats in Queensland by any incoming government since 1906.

So what is it with Queensland?

For starters, it’s decentralised with a little more than half the population living outside the capital, which makes it like no other political landscape. The city-country population breakdown in Victoria is 75-25 and Western Australia is more like 80-20.

Election analyst and former Labor senator for Queensland John Black, who runs Australian Development Strategies, says the federal ALP “just doesn’t seem to get Queensland very well at all”.

Labor’s poor performance federally in Queensland is in stark contrast to its success at a state level, where the ALP has been in power for most of the past three decades.

It’s a conundrum that has stumped political analysts for years. The same voters living on Brisbane’s northern fringe, who elected Queensland Premier and left-wing warrior Steven Miles with an 11.3 per cent buffer, have also backed Dutton at eight consecutive elections.

There are two dominant theories. The first is Queenslanders like to have a bet each way, voting for one party at state level and another federally.

Black points to the early 2000s when Queenslanders overwhelmingly backed John Howard federally at the same time as Labor premier Peter Beattie.

“If you have a strong Labor government at a state level, there’s a marked reluctance to also elect federal Labor members for the same seats,” he said.

“Quite often we would see with Howard and Beattie, federal Labor would be polling 43 per cent and state Labor would be polling 57 per cent of the two-party-preferred votes in the same seats.”

The second theory is that Queenslanders believe state Labor governments are better at delivering public services than their Liberal-National counterpart. Federally they see the Coalition as the better manager of the economy and more likely to put money back in their pockets through tax breaks.

John Wanna, emeritus professor of politics at Australian National University and Griffith University, believes it’s a bit of both.

“Queenslanders have always been very good at what is called in political science strategic voting. That is, you vote for one party at one level and a different party, another level.

“They also vote for state governments that they think are going to be ‘caring’, they’re going to provide for the hospitals, schools etc, but they’re not taxing for it.

“When they vote federally they are thinking about the economy, mining, taxation – what is the federal government going to do to us?”

Federal Labor is banking on Jim Chalmers – a born and bred Queenslander – turning the economic narrative around.

The May budget, the Treasurer’s last before the next election, is almost certain to deliver his second consecutive surplus and will help counter attacks that Labor can’t manage the economy.

But inflation will remain the government’s biggest political problem this year and it must be tamed before going to the polls.

Miles, who will lead Labor to the state election on October 26, says the importance of regional Queensland cannot be understated. “One of the key differences (in Queensland) that people in other states struggle to get their head around is just how regional Queensland is,” Miles says.

“We have those big regional cities that are really important to our economy.

“(At a state level) we know we need to win in Cairns, Townsville and central Queensland to form a majority, but it’s harder for politicians from other states to get that because in other states you can pretty much just govern from the capital city.”

Queensland’s decentralised demographics have delivered seats for Pauline Hanson, Bob Katter and Clive Palmer, with minor parties commanding decent chunks of primary vote in key marginal seats.

At the last federal election, a third of Queenslanders preferenced minor parties or independents ahead of the majors, and in the southeast corner the Greens successfully ambushed a trio of inner-city seats, including Rudd’s old seat of Griffith.

What remains unknown is if the teal factor will play out at the next federal poll.

There were no Climate 200-backed candidates in Queensland last time around but the teal movement has been quietly mobilising on the Gold Coast and Sunshine Coast in recent months.

After losing public support during the Indigenous voice debate, the Prime Minister has vowed to keep the focus on cost of living this year. And it couldn’t come a moment sooner for anxious Labor strategists in Queensland.

As one long-time Labor operative laments, the government has been too focused on “big ticket” policy items, like the voice, which for most people in regional Queensland, was a “fifth tier issue”. “I don’t think we will pick up any seats in Queensland, in fact we will be lucky to hold the ones we have,” the operative tells Inquirer. “We need to focus on delivering tangible things that we can point to and say: ‘We did that for you.’ ”

Labor optimists see Queensland as an untapped goldmine. “We are at rock bottom in Queensland, and I think there is potential for a few gains,” one federal MP says. “Anthony Albanese is relatively popular, so if he spends less time overseas and a bit more time in Queensland, I think that will go a long way.”

Bernie Ripoll, who held the seat of Oxley from 1998 until 2016, agrees Queensland needs “a lot of attention”.

“I think there are some areas of Queensland where people feel really isolated, and alienated from what’s happening in the big cities,” he says.

Albanese seems to have got the hint, jetting into storm and flood-ravaged communities of the Gold Coast and Cairns this week. Accompanied by federal Emergency Management Minister and Queensland senator Murray Watt, Albanese pledged $20m to help with clean-up efforts and another $24.25m for tourism operators.

It was welcome relief for communities in the far north seat of Leichhardt that were flooded days before Christmas and feel they have been forgotten.

According to numerous accounts provided to Inquirer from senior Labor figures, the most viable options for gains in Queensland are the sprawling seat of Leichhardt – which stretches from Cairns to the Torres Strait – and Brisbane, where the Greens pulled off a narrow win in 2022.

Leichhardt has been in Labor’s crosshairs for years. Held by Labor in the Hawke and Keating years, it was snapped up by Liberal Warren Entsch in 1996 who has prevailed at every election since then – excluding 2007.

Entsch’s impending retirement would boost Labor’s chances of picking up the seat, with the right candidate.

Watt, who had a brief stint in state parliament before entering the Senate in 2016, believes Labor’s best chance of success in Queensland is to keep the focus on a select few seats.

“I don’t think we can afford to spread our resources and effort too thinly across the state,” he says.

Miles agrees.

“I think there’s some tactical decisions for Queensland Labor about just how many seats we try to win,” he says.

“An extra three or four seats would make a massive difference, and it would give Queensland a much bigger say.”

The new Queensland Premier believes Labor’s best federal prospects are Leichhardt and Brisbane, as well as the central Queensland seat of Flynn, dominated by mining and agriculture industries, and the volatile seat of Longman, which is nestled between Brisbane and the Sunshine Coast. But to make things hard, Albanese is set to lose at least one long-serving Queensland incumbent, who will be forced out of a job by Labor’s strict gender quotas at the next election.

The rules require 50 per cent women in the combined number of upper and lower house held seats by 2025 and last year a “transitional rule” that has protected sitting MPs and senators expired.

Veteran backbenchers Shayne Neumann and Graham Perrett are under threat. Chalmers and Speaker Milton Dick (Oxley) won’t be pushed out and, as women, frontbencher Anika Wells (Lilley) and senator Nita Green are safe. Labor senators Anthony Chisholm and Murray Watt are not up for re-election and therefore are not included in the calibrations. So that leaves either Neumann or Perrett to make way for a woman candidate.

Neumann won the Ipswich-based seat of Blair off the Coalition in 2007 and has bucked swings against Labor and strong One Nation support to remain as Albanese’s only regional MP in Queensland.

Perrett also entered parliament in 2007 and has defended his seat of Moreton in Brisbane’s southern suburbs from a series of well-resourced campaigns.

Moreton is now on a 9.1 per cent margin but threatened by a growing Greens vote, with the minor party winning 21 per cent of the primary in 2022. Blair is on a more dicey 5.2 per cent buffer.

Neumann recently warned it was an “aberration” for Albanese to win the 2022 election while performing poorly in Queensland, telling The Australian: “We have got to win seats in Queensland to maintain majority government.”

Now for the tricky bit: how? For Perrett, the party needs to figure out how to talk to Queenslanders.

“You can’t ignore a state like Queensland and when you’ve got five out of 30, that’s obviously problematic,” he said. “There can’t be one Queensland message, there needs to be 30. There could be a national story but you need to translate it into Mount Isa language, Toowoomba language, Sunnybank language.”

Labor’s election review made the same point. Led by former cabinet minister Greg Combet and ex-campaign official Lenda Oshalem, the review found Labor failed to appreciate Queensland’s distinct population centres, each of which requires a “slightly different approach and message”.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout