Qatar’s World Cup has echoes of 1936

Qatar stole the World Cup 2022 hosting rights from Australia, but its cheating is just part of a deeper, darker story the world appears ready to ignore.

Next month’s World Cup in Qatar might be the most infamous sporting event since Adolf Hitler hosted the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Back then, no one boycotted the so-called Nazi Games, and neither is any country boycotting this year’s event.

Qatar brazenly broke FIFA rules to steal the 2022 World Cup – beating Australia, the US and two other potential hosts – and it has a human rights record that would shame a civilised nation.

In an effort to highlight Qatar’s shortcomings, Denmark is changing its playing strip to a low-key red shirt on which the red-shaded Danish national emblem will be barely visible. But that is charmingly inconsequential.

At least some nations discussed not attending the 1936 Olympics – there was a particularly heated debate about it in Europe and the US – but it seems we are all happy to play soccer in Qatar, notwithstanding its sometimes barbaric abuse of migrant workers and shoddy treatment of women. (Qataris will be quick to respond that it was the first Gulf country to allow women to vote – but that hardly counts; it is not a democracy.)

Qatar is a nation of migrant workers. It has a total population of 2.6 million, but of that there are only 320,000 Qatari citizens, just 8 per cent. Foreigners are 94 per cent of the workforce, with a commonly exploited majority of Indians, Pakistanis, Nepalese, Filipinos, Bangladeshis and Sri Lankans. As a result, there are almost 2.2 million men in the country but just 734,000 women.

The International Monetary Fund ranks the Qataris as the fourth wealthiest people on Earth. The country has confirmed oil reserves topping 15 billion barrels, which, with the war in Ukraine, has become an even greater export bonanza, and it is the world’s second-largest exporter of natural gas.

An export that attracts less attention are the coffins of migrant workers. The rate of industrial accidents and deaths from hyperthermia are staggering (It was 48C on June 22 and last month’s average was just under 40C).

A BBC broadcast in August quoted a report of 6500 migrant workers having died in Qatar since it was awarded the World Cup. That figure was gathered by contacting the embassies of the workers’ home countries.

Qatari officials dispute this and claim just 37 have died, of whom only three were working on stadium projects. The UN’s International Labour Organisation says the discrepancy results from government officials not including victims who have died from cardiac arrest and respiratory collapse – regularly the result of heatstroke, particularly for those engaged in heavy labour. Others are injured or killed in falls from a height.

All this for about $300 a month – if you are paid. Employers are often reported to withhold wages. In August, groups of workers claiming to have been unpaid for months mounted protests. Many were arrested and some deported.

The Nepali Times reported in July that the planes arriving from the Gulf to take men to work there on average return the bodies of three dead workers to Kathmandu Airport each day.

“Sometimes there are so many cases (coffins) that we have to rush back to the capital as soon as we drop off one coffin for the next delivery,” one driver told a Human Rights Watch team.

And while Qatar has made attempts to better protect workers from exploitation, they are still subject to punitive fees applied by recruitment agents in their home countries – these workers literally buy their jobs – and to restrictions on changing jobs and employees while in Qatar.

The country also hosts about 175,000 migrant domestic servants. In 2017, the government introduced laws to help protect them, but it is proving hard to monitor as they often live in private homes.

Three years later, Amnesty International interviewed 105 domestic workers, 90 of whom worked at least 14 hours a day and half of them 18 hours.

Most had never had a single day off at all. Some also reported not being paid properly, while 40 women described being insulted, slapped or spat at.

Some claimed they had been fondled, sexually abused and even raped by their employers or their employers’ friends. Amnesty reported that almost all had their passports confiscated, some went unpaid, while others were viciously assaulted.

“The overall picture is of a system which continues to allow employers to treat domestic workers not as human beings but as possessions,” said Steve Cockburn, head of economic and social justice at Amnesty.

Life in the squalid dormitories is equally unhealthy. One worker told a BBC reporter: “I would describe the conditions as pathetic. In the first place I stayed, Al Khor, there were 10 people to one small room, with five bunk beds and nowhere to put anything. The toilets were outside.”

He, too, had to hand over his passport, saying: “You feel trapped, like a prisoner.”

Another worker, a Ghanaian, despaired that there was no airconditioning in the cabins: “They have filthy sanitation and the food is dished out like in the Oliver Twist movie,” he said.

The Human Freedom Index, compiled annually by the respected Cato Institute and Fraser Institute, rates 165 countries and Qatar, a perennial cellar-dweller, came in most recently at 128. Russia did better. Qatar and its neighbours fill the lower regions of this comprehensive analysis of a people’s freedom “understood as the absence of coercive restraint”.

Performing slightly better is Kuwait (121) but then below it are Bahrain (143), Saudi Arabia (155), Egypt (161), Iran (166), Sudan (162), Yemen (163) and Syria was the wooden spooner. Qatar is also the home of the state-owned Al Jazeera broadcasting network that has been turning fact into fiction for almost 30 years.

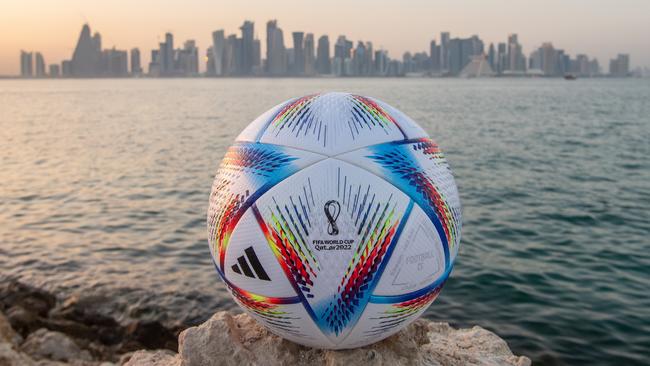

If nothing else, the World Cup preparations – in keeping with the monumental plans Hitler had for his Games site – have transformed infrastructure in Qatar since it won the right to host the World Cup in 2010. Included in the more than $300bn account are the eight futuristic stadiums (one is a renovation), that hold between 40,000 and 80,000 fans. They have been built in and around Doha, where almost everyone in Qatar lives.

Keep in mind that Qatar is not half the size of Tasmania and that there are considerably more Tasmanians than Qataris. Each venue will host an average of just eight matches, but if you are thinking of attending, note that no one will be able to buy a beer in any of them to celebrate their team’s victory.

Australian taxpayers invested $46m into the 2010 bid to bring the World Cup here, and we believed we were in the hunt right until they opened the enevelope. Australia has qualified to compete in six World Cups. Qatar has never qualified. We have a long history of competitive soccer. Qatar does not. And we would not have needed to build a single stadium.

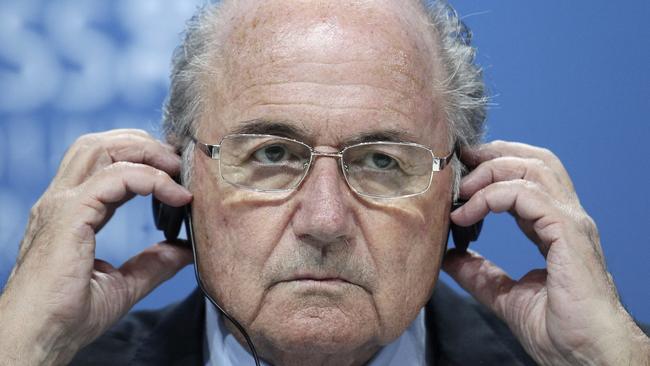

Six years later, the now disgraced FIFA president Sepp Blatter admitted privately to former Football Federation of Australia executive Bonita Mersiades: “Australia had no chance. Not a chance. Never.”

Blatter believed this was because our time zone was awkward for European and South American broadcasters. In an interview on French television, he would admit: “Of course, it was a mistake (giving Qatar the World Cup). You know, one makes a lot of mistakes in life.”

This was a reference to the extreme heat of Qatar. But there was much more at play than television rights and temperature.

FIFA’s headquarters are in Switzerland, which only in 2016 tightened its rules around commercial corruption. Well before that, the body that rules world soccer had been crippled by endless allegations and examples of corruption.

The votes that, on the same day, secured Russia (host of the 2018 event) and Qatar the World Cup shocked the sporting world, were scoffed at and remain darkly controversial.

In a report on corruption at FIFA, Forbes magazine stated: “The UK’s Daily Mirror ran a front-page headline declaring the game had been ‘SOLD’. Spain’s El Mundo went with ‘The power of gas and oil’. Japanese business daily Nikkei alleged that its country’s bid had been scuppered by money. In the US, the Seattle Times exclaimed: ‘Qatar? Really?’”.

In 2018, after years of digging, London’s Sunday Times revealed that Qatar’s bid team ran a “black operations” campaign, enlisting former CIA agents and others to generate fake propaganda suggesting there was little enthusiasm for the World Cup in its rivals’ countries.

“One of the key criteria laid down by FIFA … was that the bids should have strong backing at home,” it reported.

Several FIFA executives found to have broken its rules on influencing votes were suspended. But it went deeper than that.

Two years ago, the US Department of Justice claimed that parties working for Russia and Qatar bribed FIFA officials to secure the successive World Cups. It is a broad investigation into fraud at FIFA and its associated bodies.

“Not one official in this investigation seemed to care about the damage being done to a sport that millions around the world revere,” said assistant director-in-charge Michael J. Driscoll, of the FBI’s New York Field Office two months ago.

“Our work isn’t finished, and our promise to those who love the game is: We won’t give up until everyone sees justice for what they’ve done.”

A significant casualty of the various investigations has been Qatari football administrator Mohammed bin Hammam, a member of FIFA’s 24-man executive until 2011. The following year, he was banned for life twice for “repeated violations” and conflicts of interest.

Sydney-based author and commentator Alex Ryvchin also believes Qatar is far from qualified to host the World Cup.

“Qatar plays a sophisticated and often malevolent role in the Middle East,” he says.

“It is responsible for financing Hamas to the tune of some $480m per year, effectively keeping the listed terrorist group in power, while permitting the Hamas leadership to live in luxury in Doha.”

He is especially critical of Al Jazeera: “It is particularly insidious, presenting to Western audiences as a legitimate, mainstream media outlet, while producing openly antisemitic content in Arabic, including denial of the Holocaust and glorification of violence.

“No country is unblemished, but it is difficult to understand how Qatar, with its direct hand in regional instability and sponsorship of violence, can be considered fit to host the World Cup.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout