Pulling the infrastructure lever is harder than it seems

Business leaders call for it. Politicians talk about it. Comedy series Utopia even made fun of it. But the hurdles to infrastructure are many.

In the pantheon of economic buzzwords of our age, infrastructure must be high up. Business leaders call for it. Politicians talk about it incessantly. Surveys show people want more of it. The ABC produced an entire comedy series, Utopia, making fun of it.

This week the governor of the Reserve Bank added his voice to calls for governments to do more on the infrastructure front, following the RBA board’s decision to trim the official interest rate to a new record low of 1 per cent to boost jobs growth and inflation.

“This spending adds to demand in the economy and — provided the right projects are selected — it also adds to the country’s productive capacity,” Philip Lowe said.

“It is appropriate to be thinking about further investments in this area, especially with interest rates at a record low, the economy having spare capacity and some of our existing infrastructure struggling to cope with ongoing population growth.”

Indeed, extraordinarily low interest rates have lowered the cost of investing more. The 10-year federal government bond rate fell below 1.3 per cent last month, the lowest ever. With inflation around the same level, the federal government in effect can borrow for free for a decade.

Reflecting the views of most economists and the Reserve Bank Gareth Aird, a senior economist at the Commonwealth Bank, says: “Monetary policy can’t do anything to change the more entrenched and structural impediments to growth. The sense of taking the cash rate even lower from here is questionable.”

Lever already pulled

The infrastructure lever has already been pulled pretty hard, though. More than $500 billion has been invested in Australian infrastructure during the past decade, according to the Better Infrastructure Initiative at the University of Sydney, about double the previous decade’s spend.

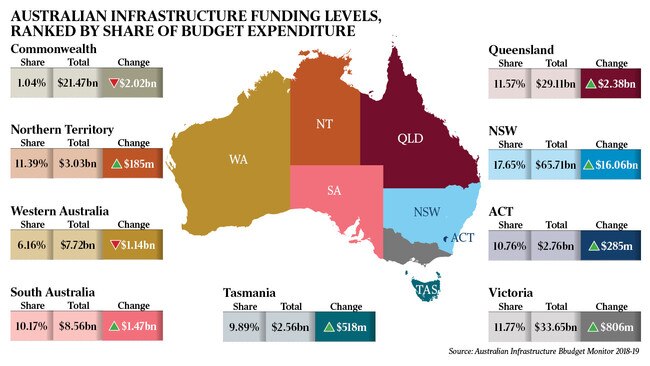

In its April budget, the federal government announced almost $100bn of spending on “economic and community infrastructure” across a decade, which sounds impressive yet makes up about 1 per cent of the national total. NSW alone is spending $93bn across the next four years upgrading and extending the state’s roads, rails, schools and hospitals. Victoria is spending a bit more than $50bn during the same period, and together they make up two-thirds of the national total.

Infrastructure Australia evaluates business cases for potential infrastructure projects, compiling a list of priorities. The current list is dominated by congestion-busting upgrades to road and rail projects in Perth, Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, with lead times, optimistically, of up to five years.

“The issue with larger infrastructure investments is they aren’t easy to mobilise and they can’t be cheaply accelerated,” Infrastructure Partnerships Australia chief executive Adrian Dwyer says.

There’s no point commissioning more tunnels without enough tunnel engineers. With a limited number of tradespeople in the economy, infrastructure pile-ons only inflate wages and construction company profits.

Costs rising

Projects have already become frightfully expensive. Laying a kilometre of highway costs from $2 million to $10m, according to the federal Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities. Based on last year’s budget papers, NSW was planning to spend $42,900 a metre on the $450m, 10.5km Berry to Bomaderry highway upgrade.

That’s nothing compared with Sydney’s light rail, which reportedly costs $600,000 a metre to wind its way from Circular Quay. That’s a modest house-and-land package or a metre of rail line. Hospitals? Before running costs, they cost more than $1.2m a bed.

“Smaller-scale, quick-to-market projects that are more easily delivered are better at stimulating the economy,” Dwyer says, singling out the removal of level crossings. “As a counter-cyclical measure, they have an immediate impact and they get plenty of people employed.”

Victoria has removed 29 level crossings and will cut another 25 before 2025, at a cost of $6.6bn. Other states could follow suit. Boring, perhaps, but general maintenance is also “shovel ready”. “We’re a big country with a road to everyone’s front door, so we have an opportunity to undertake broad-based stimulus through maintenance,” Dwyer says. “The reality is there’s a bias toward filling potholes rather than re-sheeting the roads so they last decades.”

Waste threat

The danger of all infrastructure spending is the likelihood of waste. Governments have a poor track record of spending well. “There is a widening infrastructure services deficit, with increased spending on infrastructure projects failing to deliver meaningful benefits,” says the Better Infrastructure Initiative, suggesting $63bn of road projects alone “may have no social impact or economic output”. Projects such as Sydney’s light rail, the National Broadband Network and the ever-popular Brisbane to Melbourne rail line come to mind.

Greater federal government involvement also encroaches on what are mainly state responsibilities, further confusing the public as to who is responsible for what.

To be sure, some of the smaller states could boost their infrastructure expenditure. Western Australia is spending only a third as much as NSW adjusted for population, Tasmania and South Australia about half as much. And borrowing rates have fallen just as dramatically for state governments.

Growth boosters

There’s plenty beyond infrastructure spending that federal and state governments could do to boost growth and productivity, and take the pressure off the Reserve Bank. Adjusted for population, the economy shrank in the second half of last year.

Former Productivity Commission chairman Gary Banks made a “to-do list” of ways the federal government could boost productivity growth, which has been flagging for years. Outlined at the end of 2012, it’s remarkable, almost seven years on, how few of them have been ticked off.

The commission recommended abolishing remaining tariffs, and limiting provisions for anti-dumping action. The government still imposes an average trade-weighted 4.3 per cent tariff on imports, according to the World Trade Organisation’s data for last year. Indeed, the Anti-Dumping Commission, a branch of the federal Department of Industry, has increased tariffs on steel following US President Donald Trump’s review of tariffs last year.

The commission also recommended the termination of industry subsidies. Flicking through the Productivity Commission’s latest catalogue, released last month, you can see how the $12.5bn-a-year total is carved up among different industries.

There’s $119m for the retail sector, $1.4bn for sheep and cattle farming, and $911m for financial services, for instance.

All these figures, a mix of direct subsidies with tax dollars and indirect concessions, are just the tip of the iceberg. “These estimates are conservative as they exclude harder to quantify assistance: favourable finance (loans and guarantees); local purchasing preferences, such as for defence equipment; and regulatory restrictions on competition,” the commission said. The list also highlighted the inefficiency of rules that limit the number and ownership of pharmacies, a sacred cow that hasn’t been touched.

The renewable energy target was “costly and counter-productive … and should be phased out under carbon pricing or other market based policies”. The RET, of course, is alive and well.

Advice ignored

Since Banks issued his list, the commission has produced numbers, inquiries and recommendations that have been ignored. Even modest Productivity Commission recommendations from 2016 to prune patent protections as a way of reducing vexatious and spurious claims are gathering dust.

The same can be said for the 2015 Harper review on competition policy, which is increasingly relevant. The economy has become less dynamic, evidence by dwindling rates of new firm entry.

“Workers are also switching jobs less frequently,” senior Treasury official Megan Quinn noted last month. “The rate of job switching has fallen from 11 per cent in the early 2000s to 8 per cent now and much of this decline appears to reflect a reduction in worker transitions from mature to young firms.”

A series of inquiries highlighting the excessive costs of superannuation — swaths of households, without realising it, spend more on super fund management fees than they do on utilities — underscores the importance of change in that area, too. “Establishing an efficient taxation system that incentivises innovation and productive investment is one area that could help lift productive investment,” CBA’s Aird says.

The government may argue that tax reform is in train, but its five-year tax cut plan before the parliament this week, while welcome, is a partial rollback of bracket creep. The income tax take, as a share of the economy, will be significantly higher in 2024, when the last phase of the reform is planned to kick in, than it was in 2009. That’s why the budget is returning to surplus.

Another report gathering dust, the Henry tax review, almost a decade old, had many suggestions.

This week, Scott Morrison declared this “the year of the surplus”. The government’s determination to reach and sustain a surplus makes reform politically harder. Losers of good reforms typically need to be bought off.

Tough calls unlikely

Emboldened by a surprise victory in May, the government nevertheless has a slender majority in the parliament. It seems unlikely tough decisions will be made.

While the Reserve Bank says it will adopt a “wait and see” approach on interest rates, having cut the cash rate to 1 per cent this week, most investors expect at least one more cut this year. Mortgage rates with a “2” in front could become the norm, prompting renewed activity in the housing sector and more mortgage debt.

Relying on debt to lift growth isn’t just an Australian problem. The household debt of six “small” advanced economies, including Australia and Canada, has lifted 20 percentage points as a share of gross domestic product since 2008 to just more than 100 per cent. Total credit to households here has increased to a little more than 120 per cent, higher than any other country in the OECD except Switzerland. Yet measures to make the economy more competitive would see prices fall, the opposite of what the Reserve Bank is trying to engineer with lower interest rates.

Since 1996, the Reserve Bank has promised to keep inflation between 2 per cent and 3 per cent “on average over the medium term”. Taking out volatile items, the consumer price index hasn’t increased by more than 2 per cent since December 2015. It was 1.3 per cent across the year to March. Unless it rebounds significantly, the RBA is practically compelled to cut. Weaker inflation still, even if a result of more competition or new technology, would encourage only lower rates, more debt and possibly even quantitative easing. This system of monetary policy soon may be in need of reform itself.

“Inflation is still, however, anticipated to pick up, and will be boosted in the June quarter by increases in petrol prices,” RBA governor Lowe said this week.

When the central bank is counting on higher petrol prices to meet its target, it might be time for a maintenance of the monetary policy infrastructure too.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout