‘Public entertainer’: Pablo Picasso’s complex genius

Fifty years since the death of this towering figure, it’s timely to reflect on how his nihilistic art changed the world, and the method in his madness.

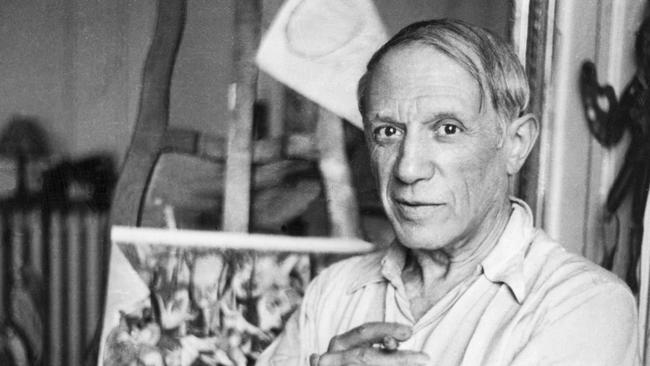

This year is the 50th anniversary of the death of Pablo Picasso, the man who the 20th century celebrated as its quintessential genius and prophet. It is timely to reflect on the role he played in the decline of Western high culture.

Picasso left around 150,000 works in total, an irrepressible volcano of creativity and virtuous technical accomplishment across an abundance of styles and art forms, with peerless originality bubbling up throughout. He was a towering figure who changed the way we see the world. A playful spirit of fun animates many of his works and some are lyrically beautiful.

But, in an interview given late in life, Picasso expressed with blistering self-honesty:

“When I am alone with myself, I haven’t got the courage to think of myself as an artist in the grand and ancient sense of the word. Giotto and Titian, Rembrandt and Goya were true painters. I am only a public entertainer who has understood his times and has exploited better than he knew the idiocy, the vanity, and the greed of his contemporaries.”

I suggest there was more method than admitted here. Picasso had worked in parallel with the most brilliant and influential, single-minded theorist in modern art, Marcel Duchamp. At the centre of Duchamp’s enterprise was a mocking of the classical tradition – its technical accomplishments, but even more its metaphysical core. In entering a urinal as a work of art in a New York exhibition in 1917, he set a profane act as equal to portraits of courage, pity and tragedy. Duchamp was laughing at the Old Masters, who had wrestled with the central truths about the human condition and sought to find echoes of transcendence and sublimity.

He questioned by what standards anyone can claim in a materialist world that their great art is any more truthful, beautiful, or good than his piece of porcelain plumbing – which is at least useful. In effect, Duchamp charges the old order with hypocrisy and superstition. Let us at least be honest. I will show you the truth – here in my urinal. Life is excrement, and at least with me you get witty puns and jokes about the futility of it all. Duchamp painted a moustache on the Mona Lisa, to make her look ridiculous.

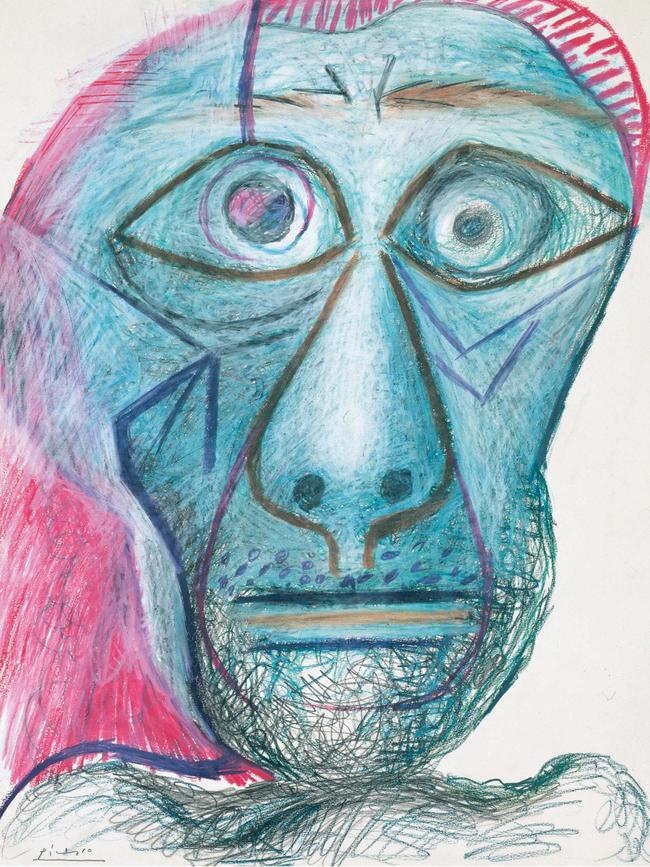

Picasso was Duchamp’s main accomplice in the artistic demolition of Western high culture, with his playful virtuosity projecting a complete nihilism. A portrait of himself in his 90s served as his last confession – a clown skull staring out vacantly at the viewer with hideous frozen dread. Arianna Huffington summed him up: “Beneath bitterness and anger was a love of life, which was trembling always on the edge of horror.”

Picasso’s egocentricity was mammoth – driven by a tempestuous will to power, and especially over his many women. He lived as a bacchanalian immoralist, obeying only his pleasure, and especially a brand of capricious sadism. His response to the one woman who escaped from him, Francoise Gilot, who died aged 101 in New York on Tuesday, was to burn a lit cigarette into her cheek and ensure that no art dealer handled her pictures. Responding to his claim that one had always to have the courage of the surgeon, or the murderer, she had told him she had contemplated that he was the devil, now she was sure.

He was not only mean-spirited, but also a coward. In court he disowned his friend, Apollinaire; he refused to intercede with the Nazis, at no risk to himself, to save the life of an old Jewish friend, Max Jacob; and during the war when a pot exploded, he dived under the table, leaving his wife and daughter unprotected. His rationalisation was the modern nihilistic one, to quote him: “I am against everything.”

As a rule, creative works should be judged independently of the character of the creator. But, in Picasso’s case the two are often inseparable. Representing himself repeatedly in his works, both grandiosely and grotesquely, he may appear as a god out of ancient mythology, a rapacious and hideous half-man, half-bull, a monkey, or even a minotaur’s skull. His nihilism had satanic vitality, as displayed in ruthlessly repulsive images of himself.

His Weeping Woman portraits, one of which is displayed in Melbourne’s National Gallery of Victoria, show the darker reality of his character. The subject is Dora Maar, one of his mistresses whom Picasso often beat, and into unconsciousness. He felt compelled to destroy the very things in Dora that he admired. In the end she lost her mind. The portraits are flat in feeling, apart from a horror that lurks in the fractured faces. The abstracting of the subject kills off any normal projection of female grief or sadness, a repressive distortion that may indicate the painter’s own guilt, his need to blur the reality of why the woman is at her wits’ end with despair.

What comes through in Dora’s mad eyes is Picasso’s own terror at the emptiness of existence.

Picasso had already introduced a similar one-dimensional mood of blank misery in his colossally influential, revolutionary painting of 1907, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. He wanted to call it The Avignon Brothel, for it began as an allegory of venereal disease. Five naked, cubist distorted women display themselves to the viewer, a trio of them mimicking the three muses, but with faces stripped of emotion apart from a frozen look of inner dread, as if they have just seen the Grim Reaper approaching. They might be characters out of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness mouthing the climax words: “The horror. The horror!” There is nothing feminine or coquettish about these three prostitutes, with their flesh voided of any sensuality. The other two women, with faces showing the influence of African masks on Picasso, look more like tortured, paralysed animals.

Robert Hughes suggested that this painting announced one of the recurring sub-themes of Picasso’s art, a holy terror of women. And an anxiety about impotence and castration, never put more plainly by any painter than in the violent dislocation of forms in Demoiselles.

Nevertheless, there is acknowledgment in this work of the high tradition of Western painting, with quotations from Goya, Ingres, and Manet. Picasso may have been the most influential 20th-century voice of nihilism, but, notwithstanding, he was a serious artist, labouring tirelessly on technique and content.

Picasso’s best-known work is the huge painting Guernica, from 1937, representing the suffering experienced in a Basque city flattened by German bombing during the Spanish Civil War. Measuring 4m by 8m, it stands as the last powerful war picture in the Western tradition. Cubist again in style, its imagery is two-dimensional, painted in black, white, and grey. The deformation of the figures gives them the mannered look of cartoon caricatures, as if they are affecting theatre poses, thereby flattening the emotional range of suffering, making it look staged. More weeping women appear – Guernica comes from the same period. Also recurring here is the weird repression and distortion of feeling, one that makes the humans look like mannequin dolls. And, the dominant and most striking central figure in the painting is a horse, its head writhing, as if screaming in terror – maybe a disfigured, unconscious self-portrait.

Guernica has none of the deep tragic gravity of its French 19th-century predecessor, Delacroix’s Massacre at Chios, which Picasso would have known in the Louvre. Indeed, Picasso’s confession to not being an artist in the grand and ancient sense is well illustrated in the contrast between these two war pictures. His own projects some of the tone of being the creation of the public entertainer he feared he had become.

Picasso is reminiscent of Karl Marx, in his demonic character and mission of destruction. He is also reminiscent of fellow Spanish painter Diego Velazquez who, in his masterpiece, Las Meninas, included a huge self-portrait as the arrogant, value-creating artist. Picasso was obsessed by Las Meninas, painting his own versions again and again, trying both to prove his superiority and to blot out, Duchamp-like, any deeper truth in the original. Las Meninas, whatever the conceit of its creator, is a profound meditation on the role of art in relation to authority and power; it is a touching portrait of the Spanish royal family, and it is much more. The difference between the case of the 20th-century genius and one of the truly great Old Masters, Velazquez, to quote critic John Berger, was that Picasso “was condemned to paint with nothing to say”.

In the end, it may have been a curse for Picasso to be born with such talent, and such a drive to paint. Apart from his early “blue period” works that show some empathy for the afflicted, and apart from moments of childlike gaiety, his vision was of disintegration. Cubism, the style he invented with Georges Braque, was, behind the playful surface, an obsessive pulling things to pieces. Henri Matisse said it all: “Picasso shatters forms; I am their servant.” At the time of the Weeping Women, he painted a Crucifixion in which Mary, the mother, drinks her son’s blood, and Magdalene clutches his genitals.

Today, we are left with the dismal inheritance. On the one hand, there is the widespread belief held in the cultural elites that nothing exists of any fundamental value – leaving the purpose of art being merely to shock, or to wallow in discontent, that is, either painting a moustache on Mona Lisa or quoting TS Eliot’s Wasteland.

On the other hand, the cities of the Western world spend extravagantly, proud in their self-importance, on galleries of contemporary art, or grand extensions such as recently opened at the Art Gallery of NSW. They then fill them with millions of poor imitations of Duchamp and Picasso, derivatives which, lacking any of the wit, the vitality, or the technical accomplishment of the originals, just echo the ugly banality, or as Picasso put it bitterly – the idiocy, vanity and greed of the times.

John Carroll recently published The Saviour Syndrome, Searching for Hope and Meaning in an Age of Unbelief.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout