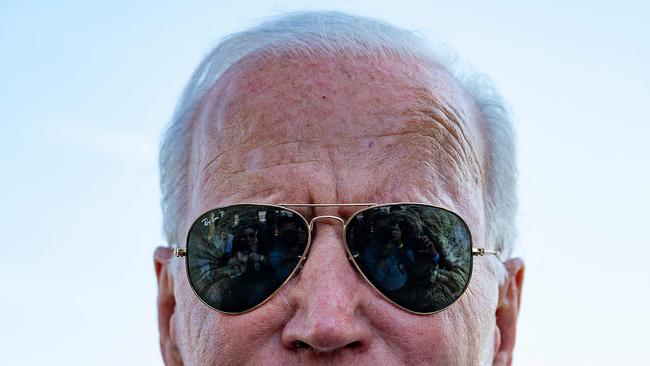

US President Joe Biden’s future not looking so bright

Overreach and bungling have eroded much of the US President’s support.

It was a mean, juvenile prank but a fitting end to a year that has been unkind to Biden, and the ruling Democratic Party.

In January last year the US was more divided than at any time since the civil rights movement, reeling from a bitterly contested election that propelled a riotous mob into the Capitol, searing January 6 into the nation’s collective memory.

An embarrassment for Republicans, given the rioters’ devotion to Donald Trump and their desire to overturn the 2020 presidential election, it appeared to be a political gift for Democrats. But the dramatic events have had negligible impact, at most, on Americans’ voting intentions.

“I think they have to wrap this up fairly quickly; fatigue is even setting in among Democrats,” says Karlyn Bowman, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute who has studied US politics for decades.

The January 6th commission, a congressional committee dominated by Democrats that is poised to issue an interim report in coming weeks, will have to produce a few smoking guns to shift the political landscape.

Indeed, a year later, Americans are less divided, itching to punish a federal administration that radically has overreached its mandate and failed to live up to its promises.

Biden was elected to end the chaos of the Trump years, to “end the pandemic” and to restore a sense of normality to American politics, not to pursue Franklin Roosevelt-style economic and constitutional reform.

“Biden has had a very rough year; it would almost take a miracle for a comeback,” Bowman says. High inflation, a bungled withdrawal from Afghanistan, the never-ending pandemic, an immigration crisis on the southern border, questions about the President’s mental fitness and a relentless union push to inject racial politics into schools, fairly or unfairly, have drastically eroded the goodwill that accompanied Biden’s victory.

Bowman points to the collapse in support among independent voters as particularly ominous.

“It’s a small group of around 10 to 12 per cent of the voting population, but it matters a lot, and the decline has been particularly large, from around 60 per cent earlier this year to something like 35 per cent,” she tells Inquirer.

Overall, Biden is more unpopular than any president since World War II, except Donald Trump, at this stage of his four-year term, hobbling his authority into the second year of his presidency as a red wave forms on the horizon.

“Even if everything were going well for Biden right now, which it’s obviously not, Democrats would still be on track to lose the house,” says John Pitney, a professor of politics at Claremont McKenna College in California.

Punters even have Trump, who hasn’t declared he intends to run, as the favourite to win the 2024 presidential election. The former president, puppet master of the Republican Party from his Florida Mar-a-Lago estate, persistently drops hints that he intends to run.

Biden’s approval rating has fallen 11 percentage points since last January to about 43 per cent, according to Gallup, which released its latest update on Tuesday. That’s only a few points above Trump’s in early 2018.

Biden is now less popular than his Vice-President, Kamala Harris, herself the least popular person to hold that office in the modern era, according to some polls.

The 2020 election was at least as much a vote against Trump as for Biden.

The former president lost the popular vote in the election by about 6.5 million votes, but Republicans in congress enjoyed a 2.9 per cent swing towards them, leaving Democrats with the slimmest majority since the civil war.

“They did much more poorly in the house and Senate than they expected to do, and my God nobody on either side thought they would actually lose seats,” says Larry Sabato, a professor of politics at the University of Virginia.

The nation’s 60 million plus (and rapidly growing) population of Hispanics, who traditionally have supported the Democrats, are now split in their support for the two major parties, 37 per cent planning to vote for each of Republicans and Democrats in the forthcoming mid-terms: “You now have many Hispanics, second and third generation, who want to roll up the welcome mat; many can’t speak Spanish,” says Bowman.

Illegal immigrants crossing the southern border with Mexico surged to a record 212,000 in July, about four times the level of the previous few years, following small tweaks to immigration rules by the Biden administration that appear to have had a significant impact.

Lockdowns and pandemic restrictions, which Democrats have championed, were more likely to cause problems for Hispanics too, Pitney says. “If you have a job where you physically have to show up, you were hurt very badly.”

The explosion of woke and cancel culture hasn’t helped Democrats either.

“On university campus a lot of people insist on using the term Latinx, which is gender neutral, but I’ve never heard a Hispanic person use it,” Pitney says.

More remarkably, in a hypothetical Trump-Biden rematch in 2024, 43 per cent of Hispanics said they would cast a vote for a second Trump presidency compared with 44 per cent for Biden, who commanded 63 per cent support among Hispanics in the 2020 presidential election.

Support has collapsed among black voters too, long Democrats’ most reliable constituency, by 18 percentage points since June to 48 per cent, falling sharply after the government announced a national vaccine mandate in September, according to a November poll by HIT Strategies.

The Democrats’ political wounds have been self-inflicted. Two-thirds of the decline occurred in August, when the US withdrew from Afghanistan, and the rest in the wake of September’s constitutionally contested vaccine mandate for 84 million American workers, which came amid the ongoing shambles of the coronavirus.

And the new year could aggravate both, with thousands of Americans and sympathetic Afghans still trapped under the Taliban regime, plus a heightened risk of terrorism in the US, as fundamentalists “encourage the use of violence (following) perceived victories over the United States”, as the US Department of Homeland Security delicately put it.

On January 7 the US Supreme Court will begin hearing arguments against various federal and state vaccine mandates, which could result in further significant humiliation.

“The Omicron variant has put a damper on everything, but it’s really inflation at this point that’s punishing Biden,” Bowman says, alluding to polls that show inflation shot up to the No.1 concern of American families in the final quarter of the year.

US inflation, above 5 per cent for seven months in a row, hit 6.8 per cent in November, a 39-year high. The surge was underpinned by huge increases in the cost of petrol and gas, and significant rises for food and used cars.

Economists are, as usual, split over the reason.

Most blame supply bottlenecks globally as nations lift pandemic restrictions; a smaller group points to the enormous increase in the money supply under the Trump and Biden administrations that is having an inevitable, if delayed, impact on prices.

“You can’t campaign in 2022 on the pandemic being not nearly as bad as it could have been; that’s not a slogan,” Sabato says.

Like all governments eager to put the damage of Covid-19 restrictions behind them, the Biden administration has trumpeted economic and jobs growth, but it’s the levels that matter.

The economy remains a shadow of its 2019 self, having only recently limped back to the size it was in 2019, and with about three million fewer jobs to show for it.

“It’s 11 months away, the economy under the surface is getting better, which is what the booming stockmarket is anticipating, and the pandemic will fade,” Sabato says. Time will tell.

The administration’s biggest own goal must be the pandemic, however.

“The first thing Joe Biden and I will do in the White House is get this virus under control,” Harris said in November 2020.

“We’re eight months into this pandemic and Donald Trump still doesn’t have a plan to get this virus under control. I do,” Biden said late in 2020 on the campaign trail, blaming the former president for Covid deaths.

Of the 820,000 US Covid deaths, more than half have occurred since last January.

Pinning the blame for Covid deaths on the Trump administration, which, like Biden’s, has almost no constitutional power to change individual behaviour or dictate to states or cities, was unfair.

They were brave promises scientifically too, given the likelihood of future variants and the already clear failure of the raft of lockdowns, mask mandates and byzantine physical distancing requirements to snuff out the highly contagious virus.

Biden promised in December 2020 he would not mandate vaccines, and after he did so last September, their effectiveness began to unravel as Omicron cases exploded across the nation last month, leaving the party to defend an increasingly unpopular and ineffective policy.

The pandemic of the unvaccinated became the pandemic of the unboosted – an unsustainable political proposition in a nation where more than a fifth of adults refuse to get even their first dose of Covid-19 vaccine.

“People are done with restrictions and that’s why you don’t hear politicians talking about returning to a lockdowns, people would just resist it and they know that,” Pitney says.

Some Americans became so fed up they moved states entirely. More than a million Americans moved to another state in the 15 months to July last year, and almost 600,000 of them to Texas, Florida and Arizona, which controversially eschewed many restrictions. California, New York, and Illinois, the most restricted states, by contrast lost people in droves, with migration up by as much as 75 per cent on prior years.

Vaulting ambition has undermined Biden’s legislative achievements so far, which have been perfectly satisfactory by any historical standard. Setting aspirations so high set the President up to fail. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act to improve the nation’s roads, ports and railways should have been enough. Also known as the bipartisan infrastructure framework, the legislation was signed in November and is worth around $US1 trillion ($1.4 trillion) across a decade.

“We need to rebuild our infrastructure, but that’s not how people vote; I’m not sure in this environment it would have mattered if they passed the bill a week before the election, much less that it happened a year earlier,” Sabato says.

The BIF, combined with the popular American Rescue Plan, a $US1.9 trillion stimulus package passed in March that supercharged unemployment benefits and boosted child welfare payments, could have been enough for one year. But Biden, pushed by the left flank of the party, kept pushing for Build Back Better, a multi-trillion-dollar series of climate change, welfare and education programs that would have radically transformed the relationship between the federal government and the individual, but failed spectacularly last month.

Its failure undermines a US pledge to slash carbon dioxide emissions by 50 per cent by 2030, but perhaps West Virginia Democrat senator Joe Manchin, who torpedoed the bill, might have saved the party from politically lethal accusations of fuelling inflation further.

“The bills they wrote exceeded the mandate they got, and they need a basic lesson in mathematics; when you only have 50 senators every senator is king,” Sabato says, referring to the 50-50 chamber, where the Vice-President has the casting vote.

A searing year will prompt Democrat soul-searching in 2022. Even Hillary Clinton implored Democrats to engage in “careful thinking about what wins elections outside deep-blue districts”.

The Squad, a noisy left-wing faction led by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, insists Biden’s agenda this year should include radical reform of the nation’s electoral system, snuffing out states’ rights to manage their own elections, and dogged pursuit of a new Build Back Better bill.

Similarly, plans to pack the Supreme Court with more sympathetic judges, an idea the former senator Biden once excoriated, or to give statehood to the District of Columbia, which coincidentally would provide an extra two Democrat senators forever, remain on the Squad’s agenda, despite little hope of broader appeal.

“The far left of the party is very powerful, but beyond New York and San Francisco they aren’t very numerous,” says Bowman. “The whole party has been pulled to the left over the course of the Obama and Trump administrations.”

The “upstairs-downstairs coalition” of high-income earners and poorer workers that the modern-day Democratic Party has become risks collapsing with too many people upstairs.

“I’m speaking from La Crescenta, Los Angeles, an upper middle-class suburb, which in the not too distant past was solidly Republican, now it’s Democrat,” Pitney says.

Indeed, the ill-fated Build Back Better bill included a sizeable tax cut for high-income earners, especially those living in Democrat states, by proposing to uncap how much households could claim in state and local tax deductions.

Republicans have their own problems. “A sizeable majority would prefer Trump not to run in 2024 and around a third have drunk the Kool-Aid,” Sabato says.

Trump’s supporters, the bulk of whom still believe the 2020 election was stolen, booed him at a speaking event in Texas last month when he encouraged the audience to get vaccinated against Covid-19.

For now, the era of Reagan and Bush republicanism is over. Liz Cheney, the daughter of George W. Bush’s vice-president, Dick Cheney, has been kicked out of the Republican Party and is on track to lose her Wyoming congressional seat for criticising Trump over his involvement in the January 6 riot.

“Trump has a large bloc of crazies, even in congress; and the far left is where the energy comes from for the Dems, so they are both stuck singing songs off-key,” Sabato says.

If the economy improves, the mid-term elections might not yet be the drubbing Republicans are hoping for.

“Don’t be surprised if the January 6 committee comes up with more than people are expecting,” Sabato says, suggesting he knew, from sources, that it would.

“If the fact was that this was a real plan for a coup, while that will mainly motivate Democrats, they usually don’t turn out at the rate Republicans do in the mid-terms, so it could matter.”

Pitney says redistricting, whereby state legislatures and commissions periodically gerrymander the electoral map to help their own side, will help the Democrats, too. “The Republican seats are getting more Republican, Democrat seats more democratic.”

On current trends, Americans will be lining up with brickbats this November to punish Biden and the Democrats, delivering a crushing victory to Republicans so soon after their reputation was trashed in the eyes of many.

A defeat should provide lessons on how to realign policies and priorities to maximise the party’s chances for the presidential showdown in 2024. Those lessons, however, might be ignored.

“Let’s go, Brandon, I agree,” Joe Biden said on Christmas Eve as he took calls from well-wishers, naively agreeing with an Oregon man who ended his conversation with the slogan that went viral in October. (NASCAR racer Brandon Brown was filmed in front of a crowd chanting “F..k Joe Biden”, which his NBC interviewer suggested was actually “Let’s go Brandon”, in support of Brown.)