Pragmatism is good but goes only so far

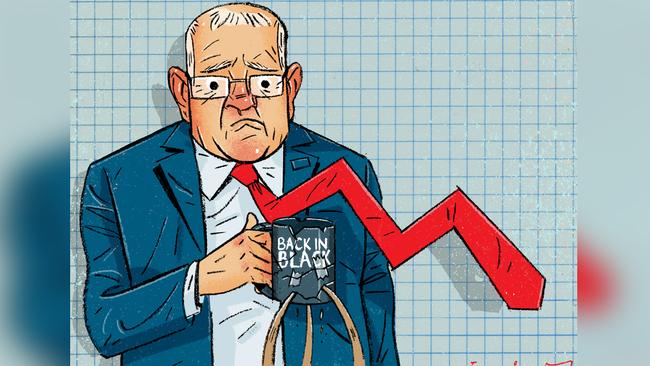

Can Scott Morrison make the right decisions to lift us out of recession?

Next month Josh Frydenberg will hand down a budget that was supposed to be in surplus. We were told we were already “back in black”, remember? Instead the budget will be in deficit, the largest in the history of this nation. That will see national debt, which has already doubled since the Coalition came to office in 2013, continue to balloon.

We know unemployment usually rises far more quickly than it comes down, history has taught us that. The Treasurer made that exact point when moving to legislate the JobKeeper payments to keep people in work.

But there is only so much a government can do.

This week the Australian Council of Social Service released research it commissioned from Deloitte, with modelling showing that reducing JobSeeker payments could put a further 130,000 Australians out of work. At first glance it seems an odd finding, given that people on JobSeeker are already out of work. But the reason is an obvious one.

People on low incomes, which anyone on unemployment benefits certainty is, live hand-to-mouth. That is, they spend what little money they get each fortnight. They don’t save, thereby withdrawing money from the economy. Therefore, when their income is reduced, billions of dollars less is being pumped back into the economy each fortnight.

Less money is spent on retail, in particular, which means the jobs that money flow is maintaining are put at risk. That is where the 130,000 figure comes from. In addition to the value the extra payments provide for recipients of government assistance, that money also helps pump-prime the economy, in turn saving jobs.

The price of doing so is more debt, but the hope is a pay-off comes in the longer term: jobs maintained, improved living standards for welfare recipients and hopefully enhanced economic growth (what Paul Keating would call “growing the pie”).

Economic conservatives dispute the value of this chain of events, indeed whether it actually happens. They claim higher unemployment benefits can be a disincentive to work, so they need to come down for that reason alone.

They also say that ballooning debt is a first-order problem, and argue we can’t burden future generations with it. That said, fewer Coalition MPs are mounting this argument any more in the context of the current crisis.

All of the above is a necessarily nuanced debate, which frankly is beyond the comprehension of many of our elected MPs, untrained in economics and commerce, some lacking in logic and common sense at the best of times. Politics doesn’t always lend itself to nuance anyway, modern politics in particular. Simplistic slogans have replaced the weighty economic debates of the past. However, in the wake of this crisis as a nation we need the tone of the debate to lift.

How nations respond to the coronavirus-induced global recession will play a vital role in how prosperous they are when we all come out the other side. Make good decisions and Australia will be on the right side of history, extending our decades long run as the “Lucky Country”, as Donald Horne once described us. Make bad decisions and we risk emulating Argentina, which slipped down the global prosperity ratings during the 20th century.

It is therefore an incredibly important time for policymakers. Unfortunately, our political settings aren’t match fit for the challenge. Our democratic institutions aren’t working adequately. Parliamentary debate is being stifled by the lack of sittings and the exclusions caused by social distancing. The federation is broken as states and the commonwealth squabble over their respective power-sharing arrangements.

Partisan debates on the economy aren’t what they used to be: since losing the 1996 election and deserting the proud economic legacy of the Keating era, Labor can’t compete in the court of public opinion when it comes to the economy. With the state of the economy front and centre, and polls confirming Labor is a mile behind the Liberals as preferred economic managers, Scott Morrison has the next election in the bag. If the recovery is swifter than expected, he gets credit. If it’s slower, even made worse by poor policy choices, Morrison simply asks voters if they are willing to risk handing the reins of power over to Labor at such an important time. He knows the ballot box answer will be no.

That means a guaranteed four to five more years of Coalition government deciding how Australia reshapes its economy in the wake of the pandemic. So we turn our attention to how well equipped it is to do that.

Genuine economic liberals within the Liberal partyroom are few and far between these days. Economic literacy is even scarcer. Reactionary conservatives instead run rampant within Coalition ranks. The Prime Minister’s preferences have long included economic intervention, not economic liberalism. For example, when he clashed with then treasurer Joe Hockey in cabinet in the Coalition’s first term over whether the government should subsidise SPC Ardmona, Morrison was all for it. Or this week when he announced plans to build a government-owned gas-fired power plant to compete with the private sector.

At one level Morrison’s pragmatism has its upsides. It means he won’t put ideological dogma first. But his pragmatism is political, not economic, meaning the pathways he chooses are likely to be all about winning elections, not good policy.

Occasionally the coincidence of duality may arise if we’re lucky.

More likely tough but necessary decisions involving economic reform will be shelved rather than enacted, as happened during the Fraser years when the Campbell review (recommending micro-economic reforms) gathered dust on then treasurer John Howard’s bookshelf. The do-nothing years of the Fraser government (1975-83) didn’t hold Australia back because they gave way to the reforming years of Bob Hawke and Keating.

Who seriously sees such impressive figures on the opposition benches now? And at a time of far greater crisis and need.

Peter van Onselen is political editor at the Ten Network and a professor of politics and public policy at the University of Western Australia and Griffith University.

The unemployment rate fell dramatically this week, catching analysts off guard. Of course when JobKeeper gets withdrawn next year that is likely to see the rate head north once again, as Treasury has forecast. JobSeeker payments also are coming down, moving back towards the paltry rate Newstart was set at before the coronavirus crisis caused this recession.