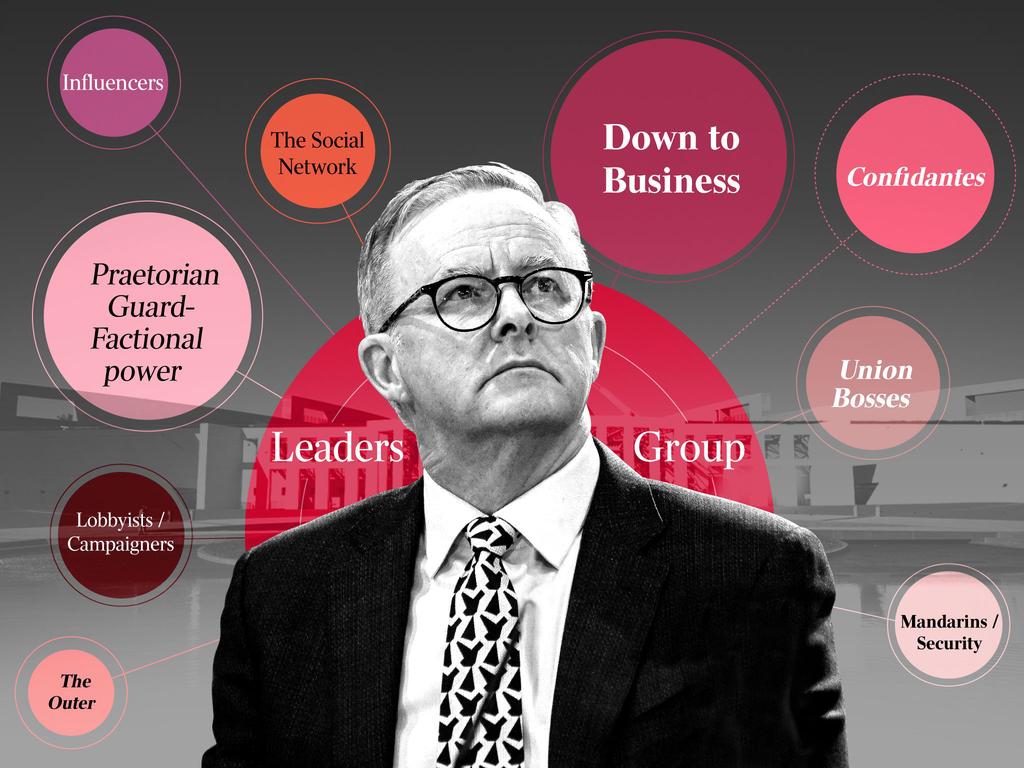

Power & the PM: Meet Team Albanese, Labor’s power network

For 40 years Anthony Albanese has been watching and waiting, building a trusted clique, often in the shadows and in defiance of his ideological roots | SEE THE POWER LIST

For the past 40 years Anthony Albanese has been watching and waiting.

He has witnessed Labor at its most successful, as a staffer during the Hawke-Keating years, and at its worst, when he was a minister at the coalface of the Rudd and Gillard governments.

Some compare the 59-year-old’s career path to that of John Howard’s progression through the Liberal Party.

Howard lost the leadership, won the leadership and emerged to become prime minister with the experience of a leader who understood how privileged yet fragile it was.

Albanese likewise had his own aspirations smothered, was rejected for the leadership, only to rise again from the rubble of his party’s misfortunes, having witnessed its mistakes, to finally become leader and then Prime Minister.

“You don’t get to be prime minister as leader of the Labor Left unless you can do something remarkable, and bring people with you,” a close friend and former colleague of Albanese told Inquirer.

“I’d say, he’s an overnight success, 40 years in the making.”

But one doesn’t become prime minister without having created an impenetrable arc of power around their leadership, constructed from a trusted clique of friends, advisers, bureaucrats, business leaders and parliamentarians.

Albanese, a Sydney-based former tribal warrior for the Socialist Left, has been building his own power base carefully and purposefully over decades, often in the shadows and sometimes in defiance of what observers would see as his ideological roots.

“He is a bit of a paradox in that sense,” says another source close to Albanese.

Albanese was recently described by George Megalogenis as a “radical traditionalist” – a term that resonated last week when the Prime Minister stared down republican elements in response to the death of Queen Elizabeth II.

The apex of Albanese’s inner circle of power is his newly fashioned Leaders’ Group – loosely modelled on Scott Morrison’s “leadership group”.

This cadre includes Albanese’s deputy leader and Defence Minister Richard Marles, Senate leader and Foreign Minister Penny Wong, Finance and Women’s Minister Katy Gallagher, leader of the house and Workplace Relations Minister Tony Burke, Treasurer Jim Chalmers, Health Minister Mark Butler and Trade Minister Don Farrell.

It is a factionally balanced grouping with four from the Labor Right – Burke, Farrell, Chalmers and Marles – and the rest from the Left.

The Leaders’ Group meets every Sunday or Monday at The Lodge before a parliamentary sitting week for high-level discussions around tactics and other issues. Albanese’s chief of staff, Tim Gartrell, and ALP national secretary Paul Erickson also sit in on the meetings.

“In terms of party management, Albanese comes from the Left, they are in the minority, so he keeps a good relationship with the Right. In that regard, he relies on Marles and Farrell to keep things under control in the Right,” a senior Labor MP said.

On the Left, Albanese has another group that consists of MPs Pat Conroy, Tim Ayres and Andrew Giles. These are his praetorian guard.

Wong, from the Left in South Australia, holds a separate and unusual place in that while she is considered to be progressive in terms of social policy, she can be conservative when it comes to economic policy.

“The Conroy, Ayres and Giles group would tend to be on the progressive side of economics, where she doesn’t fit exactly into that. She has a strong and private relationship with Albanese, although they don’t always see eye to eye,” a Labor insider said.

But others say the degree of power that Gallagher now wields should not be underestimated. “She has a lot of influence with Albo,” says a source close to the power group.

“Paul Erickson is very important, he turns up to all the leaders meetings.”

Butler – who ran Albanese’s failed bid for the leadership in 2013 – is also regarded as a close friend and confidant of the Prime Minister.

While Albanese has presided over a period of stability between the warring factions, it almost came undone within the space of a year in late 2020, when renegade NSW Right MP Joel Fitzgibbon began agitating for a leadership spill.

“What has been remarkable was in opposition, the way Albanese dragged the party to the centre, after Bill (Shorten) had taken us way too far to the left,” a colleague told Inquirer. “It was a smart move, electorally of course, but it also meant he doesn’t have trouble on his right flank. But he had to make sure he had control of the left flank as well.”

Albanese’s path to power has been one less travelled by Labor leaders historically, with the exception perhaps of Kevin Rudd.

Despite historic links with the Australian Manufacturing Workers Union, he has never had a traditional union power base behind him.

“Unlike other ministers, he never worked for a union,” a senior caucus source said.

“He went early on into the party structure in the office of Tom Uren … he had strong links to left unions for support but he hasn’t had that pedigree as others in the party have.

“Whereas most around the cabinet table have worked for a union, you wouldn’t instinctively think of him as a union person.”

The political expression of Albanese’s use of power is displayed not only through reshaping the machinery of government to deliver his agenda, but also those elements he has left in place to ensure continuity and stability across the economic and national security architecture.

It recognises that any radical movement in this space, or overtly political appointment, as tem

pting as it might be for some of his colleagues, could be perilous for a new Labor government that, electorally, has been given the benefit of the doubt on its commitment to the two primary functions of government.

Albanese has made a point of leaving the national security architecture completely untouched.

Andrew Shearer, who heads the Office of National Intelligence, is said to have a good working relationship with the Prime Minister, despite serving as cabinet secretary under Morrison and as national security adviser to both John Howard and Tony Abbott.

Shearer is regarded as a key pillar of continuity along with Mike Pezzullo, the secretary of Home Affairs who worked in defence under the Keating government and as a former adviser to Kim Beazley, and Defence secretary Greg Moriarty.

ASIO director-general Mike Burgess and Australian Signals Directorate chief Rachel Noble both remain in place and are considered highly by the new administration.

Albanese has taken the same approach across key economic portfolios, keeping Treasury boss Steven Kennedy in his post while promoting senior Treasury officials into new secretary positions.

Former Treasury officials Jenny Wilkinson and Meghan Quinn – who worked under Kennedy and were central figures in the Morrison’s government’s economic pandemic response – have been tapped to lead the Finance and Industry departments.

“His approach has been about stability and continuity in national security and economic portfolios,” a highly placed government insider said.

“Chalmers and Kennedy go way back, Pezzullo worked in the Keating government and for Beazley in opposition. The weathered relationships are solid. And the national security architecture and economic portfolios have been left alone.

“He knows what would happen if you opened up a flank on security.

“So why have that fight? Why would you bother?”

After winning the May 21 election, Albanese moved quickly on three priority department secretary appointments.

At the top of Albanese’s list was the high-profile recruitment of Professor Glyn Davis and axing of Morrison’s former chief of staff, Phil Gaetjens at the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. Professor Davis – a former Griffith University and University of Melbourne vice-chancellor who served under Wayne Goss and Peter Beattie as a senior Queensland public servant – had been the Prime Minister’s top pick leading into the election.

Jan Adams and Jim Betts were installed as secretaries of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and Department of Infrastructure, Transport and Communications – replacing Kathryn Campbell and Simon Atkinson, who were considered close to Morrison.

Other key appointments made in Albanese’s APS shake-up included David Fredericks (Department of Climate Change, Energy, Environment and Water), Natalie James (Department of Employment and Workplace Relations) and Gordon de Brouwer (Public Sector Reform).

Beyond government, Albanese has an eclectic group of friends and staffers who make up what could be described as his social network.

“By nature, he is gregarious. He casts his net wide,” a friend of Albanese said.

Clayton Gunning, Sherie and Scott Dewstow are old mates from his Camperdown social housing upbringing who remain close to Albanese. They were among eight childhood friends who surprised Albanese in Canberra during the first parliamentary sitting week following the election.

Inner West Council Mayor Darcy Byrne, a former staffer and long-time factional ally, is an important sounding board for Albanese, along with ex-campaign manager Daniel Barbar.

Leading the nerve centre inside the Prime Minister’s Office is Gartrell, a close friend who ran Albanese’s inaugural campaign for Grayndler in 1996, and veteran staffer Jeff Singleton.

Albanese has brought back former staffers and friends who have helped guide his political career. These include Alex Bukarica, a long-time mate and godfather to his son, Nathan, “caucus whisperer” Mal Larsen and Moksha Watts. Senior economics adviser Alex Sanchez joined the office of his former University of Sydney classmate from Deloitte in 2019.

Industry Super Australia chair Greg Combet, a former Labor minister and ACTU secretary, is highly regarded by Albanese and will play a central role in finding common ground between cashed-up super funds and the government’s ambitious policy agenda.

Mike Mrdak, who ran Albanese’s infrastructure and transport department during the Rudd-Gillard years before being moved on by Morrison, is another sounding board for Albanese.

Other Labor elders from whom government ministers seek advice include Stephen Smith, Wayne Swan, Paul Keating and Beazley. Sam Mostyn, a former Keating staffer who has forged a successful business career, was recently appointed to the Climate Change Authority board and chairs the government’s Women’s Economic Equality Taskforce.

While union bosses naturally enjoy greater access under Labor governments, those considered to wield the most power are Sally McManus and Michele O’Neil (ACTU), Tony Maher (CFMEU mining and energy division president and a friend of Albanese), Gary Bullock (UWU vice-president and political director who wields enormous influence over the Left faction) and Right faction union chiefs Michael Kaine (TWU) and Daniel Walton (AWU).

Former Queensland Labor premier Anna Bligh, now the chief executive of the Australian Banking Association, says Albanese had long-established relationships around boardroom tables that spoke to his ability to build networks of power.

A source close to Albanese – who has developed a myriad private sector contacts over decades – said “what’s interesting is that he’s always been a high flyer, he’s just done it really quietly”.

“He was always regarded as on L-plates, and ‘small target’. He’s never been a small target, he’s been around for ages,” the source said.

“He understands government, he’s the consummate parliamentarian, he understands power structures and how you can use those to effect change.

“He’s always had strong relationships, the thing about him is that he has always been underestimated.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout