Post-pandemic, we’ll need a boost from immigration

Immigrants get blamed for a lot of social ills these days – unless their offspring are doing well at the Olympics.

My study of immigration history and my personal history as the daughter of an Italian immigrant, has taught me that immigration is such a complex social phenomenon that one factor, let alone one number, cannot sum up all the significant issues. However, that has not stopped commentators seizing on a single number to push a particular view of immigration policy.

A few weeks ago Peta Credlin raised the issue of the number of immigrants Australia accepts and the type of skill sets that we need. She was right about the skills aspect of current immigration policy but wrong about using one raw number to illustrate its flaws.

To use a particular number, 100,000, as an ideal number of immigrants is a false argument. This fails to take into account one overriding factor governing immigration policy: levels of natural population growth. Ours is below replacement and has been declining for many years.

It is true that although we have had nil immigration for the past 18 months, Australia has experienced a remarkable economic resilience.

However, the past year is useless as a snapshot of Australia without immigration because 18 months during a pandemic is a unique period of emergency. The economy has bounced back for two reasons. First, our commodities exports are in strong demand. But the other overwhelming reason is that the government has poured $311bn into combined economic and health support.

Without that support we would have been in trouble. JobKeeper alone has saved at least 700,000 jobs. It is these measures that have kept the economy afloat. Furthermore, it is no surprise with the shortage of labour that wages have started to grow. However, as the pandemic begins to wane, this will not be sustainable without a return to higher immigration levels.

At the moment Australia’s total fertility rate is officially 1.7, but during the pandemic it has dropped even further and there are predictions it will go lower than 1.6. It is the lowest it has been in our history. If we do not have higher levels of youthful immigrants, we simply will not have enough births to maintain our population and sustain our current levels of productivity that maintain our high standard of living.

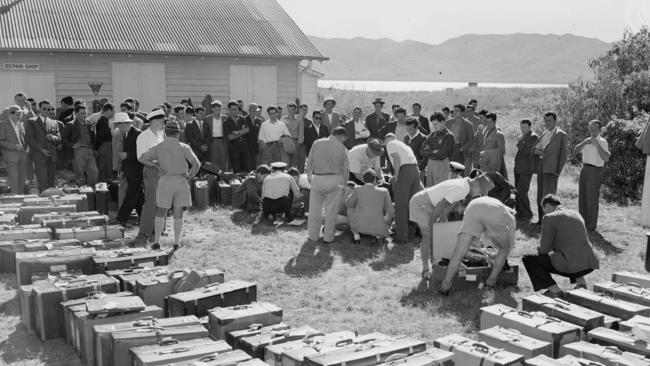

Interestingly, when post-war immigration was at its height we also had high natural rates of fertility. This combination caused a dynamic shift in Australia’s economic and cultural outlook. We went rapidly and successfully from a monoculture of 10 million in 1960 to a culturally and linguistically diverse nation of more than 25 million. But from the 1970s the natural fertility rate has bumped along intermittently, with immigration contributing to population increase accordingly.

Sometimes immigration was relatively low, as in 1984 when it contributed only about 27 per cent to the total growth of population. In 1988-89 the mix of immigrants changed in favour of a skills-based program. By the end of the decade, as we came out of recession, a combination of family reunion and skills-based immigration contributed 54 per cent of total population growth.

Towards the end of the Howard years the decline in natural fertility became a policy issue of some urgency. Although immigrants can contribute to population growth, because they arrive in the middle of their productive years they do not contribute to the total population profile as well as babies. Furthermore, in the second generation, immigrants rarely have any more children than the native born. Consequently, there was a national policy to increase the birthrate. “Have one for your country,” treasurer Peter Costello said. To a certain degree it worked. In 2008 the birthrate went to 2.02, which is close to replacement.

However, immigration also went up. Why? It was after the recession, productivity really ramped up and the balance towards higher immigration actually shifted during the Howard years. In 2007 immigration reached 158,000. By 2012 it was 190,000, and it stayed at that level during the Abbott government. If the fertility rate does fall to less than 1.6 as predicted, then we will need to maintain at least the level of 200,000, as before the pandemic.

Immigration, unlike natural population growth, can be adjusted, it can be turned on and off, but we should never lose sight of the fact it is part of our culture. A third of us were born overseas. But although Australians are crammed into six cities, the myth that immigrants cause urban congestion persists. It is lack of decentralisation that causes that problem. Who can blame people for wanting to live where they can work?

Unfortunately, I still hear comments like one recently about “some cultural groups” being responsible for the spread of Covid in western Sydney, despite the fact the infection came from the eastern suburbs.

As we move out of the pandemic, there is a case for higher rates of immigrants with practical skills, especially trades, and fewer immigrants with tertiary qualifications. However, many immigrants were overseas students trained at our tertiary institutions, and considering the state of Australian school education it is unlikely we will be able to produce enough professionals of our own in future.

Immigrants get blamed for a lot of social ills these days, from urban congestion to spreading Covid in Sydney’s west – unless their offspring are doing well at the Olympics. Then we can trumpet their success to illustrate our multicultural inclusiveness.