PM’s kowtow a necessary evil of doing business

The entire charade of the PM’s visit has been on China’s terms but that doesn’t mean it’s not in Australia’s interests.

The entire charade has been on China’s terms but that doesn’t mean it’s not in Australia’s interests. The invitation was an olive branch from Beijing after a sustained period of hostility during the Morrison years, that had damaging economic consequences.

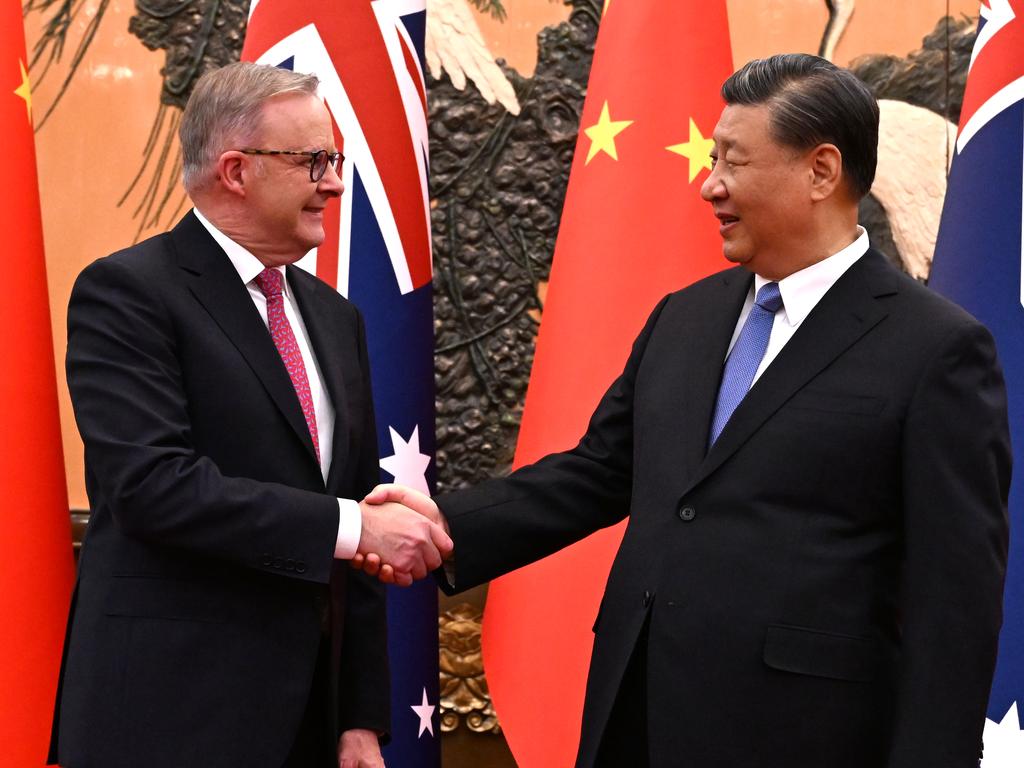

An Aussie prime minister prepared to kowtow matters to the Chinese, which is what Albanese had to do to repair the relationship. The gesture is seen as a sign of respect and submission. Albanese put a premium on the economic benefits of doing so.

While the Middle Kingdom isn’t a democracy, it certainly understands what advantages it can derive from the process of democracy and capitalism elsewhere.

Australia under the Coalition ramped up its rhetoric against China on security matters and the Chinese responded with sanctions. In these frosty dealings, diplomatic channels closed down and backdoor efforts to reopen them failed. The public rhetoric coming from Scott Morrison was simply too strong – unless a circuit-breaker could be found.

That circuit-breaker was Labor winning last year’s federal election. Had the Coalition won, only a humiliating public backdown by Team Morrison would have sufficed. The sanctions would have had to bite hard for our proud former prime minister to do that, though, especially given the internal criticism he would have received on his right flank.

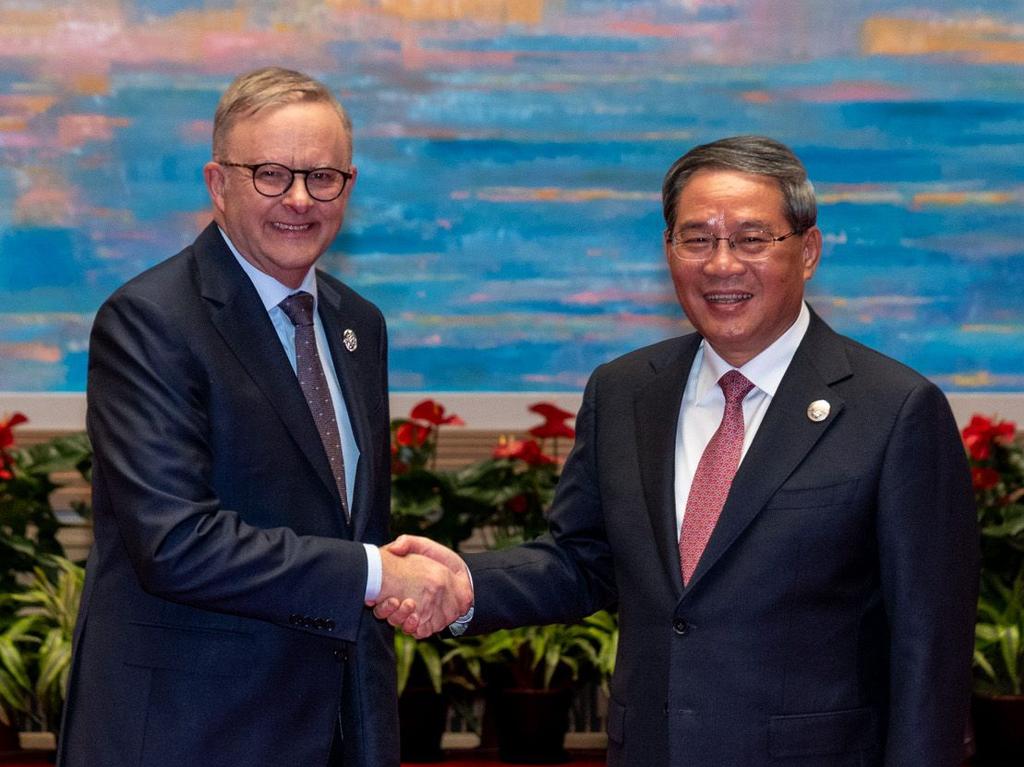

But there was a change of government, so China extended the olive branch to the new Labor administration: reopening some trade (not all) while watching the rhetoric that followed. Once satisfied Albanese wasn’t going to emulate the aggressive posturing of his predecessor, an invitation for the official visit soon followed.

In turn, Albanese has invited Xi to visit Australia again, but there will be no second address to the parliament for the Chinese President if he does. His first address in 2014 was hailed (incorrectly) as a long-term commitment to democratisation by China. Xi smiled politely at the misunderstanding at the time. Since then he has declared himself leader for life, not even submitting to the Communist Party’s appointment processes, much less democratisation.

China understands its emerging power and acts accordingly. Its communist regime has no intention of democratisation. China takes a long-term view when it comes to international relations, unsurprising for a civilisation many millennia old and used to being the largest, most advanced society across the globe for most of that time.

Westerners often fail to understand the engrained cultural superiority within the Chinese leadership such historical dominance spawns, coupled with a belief that the past 200 years were an aberration to be learned from and corrected, given the insult. Thousands of years of Chinese dominance were briefly punctuated by a failure to explore, trade and develop firearms. Modern China has learnt from such mistakes – just look at where it directs government spending.

Journalistic scribblings about Australian leaders visiting China usually overstate the importance of how such trips foster relations.

Meanwhile some commentators lay into prime ministers for spending too much time abroad, especially going to China, as though leaders should tether themselves to their country of origin instead.

Albanese will head to the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation summit in San Francisco next week, as he should, to inevitable criticism he’s away too often. Failure to attend, sending a subordinate instead, would be a sign he is rattled by criticism in the wake of inflation and interest rate woes.

We are but one of many smaller trading nations modern China deals with. The power is all one way. If in meetings we politely condemn China’s treatment of domestic minorities, or its interactions with its nearest neighbours, its leaders will nod politely and continue to go about their business as they choose. The comments represent nothing more than a red herring in their eyes. But if we push the point too hard and too publicly, China will retaliate to dissuade future political leaders from using the same rhetorical force, knowing full well that democratic elections can quickly replace recalcitrant leaders – not something Chinese officials need to worry about.

This was always China’s strategy when it came to Team Morrison – patience.

If we want an Australian citizen held in detention released, China will release them if that suits its interests. If, however, it calculates that such actions might cause domestic unrest or spark calls for further actions that risk undermining the ruling party, no outcome will be forthcoming. All Australian negotiators can do is ask politely while briefing their political leaders to avoid public condemnation likely to damage the process.

Security experts claim kowtowing on trade risks emboldening China’s actions in areas such as cyber crimes. What rubbish. China will always do what it wants on that front unless somehow stopped by a more powerful adversary.

Australian wine and beef are pleasing to the palate but not a deal breaker when it comes to the Chinese putting security self-interest first. A failure to do that contributed to China’s decline from the mid-1400s onwards when it scuttled its treasure fleet and turned inwards. Britain’s victory in the mid-1800s Opium Wars gave way to more than a century’s worth of domestic tumult, before Deng Xiaoping’s market reforms in the late 1970s set China on a course back to power supremacy on the international stage, taking advantage of the Cold War climate.

Australia has no influence over Chinese decision-making beyond the tone of engagement dictating the response we get. China isn’t an ally and it isn’t a democracy. It is an emerging superpower and we are a middle power at best. Its vision for our region includes Australia serving as a modern tributary state rather than a hostile advocate for US interests. Diplomats hope the choice never becomes a binary one. China uses its economic clout to do the same.

In centuries past the practice of kowtowing involved touching the ground with one’s forehead as a show of respect and submission. The practice was most identified with meeting the Chinese emperor and was a ritual tributary state dignitaries would perform. While the formal practice is antiquated, when dealing with China the sentiment hasn’t changed. For a trade-dependent nation such as Australia, it is a necessary evil when doing business.

Peter van Onselen is a professor of politics and public policy at the University of Western Australia and Griffith University.

Anthony Albanese visited China, met President Xi Jinping and came home with some important advances to help rekindle trade links.