PM’s battle to reconcile faith with equality

We must stop framing the debate as the right to discriminate versus the right to equality … we need both.

Before the last election Albanese promised what Scott Morrison failed to deliver – to legislate a religious discrimination act offering guarantees for religious freedom in Australia since there is no such federal law. But this was always a daunting prospect given his tied commitment – the removal of exemptions that religious schools enjoy from the Sex Discrimination Act, long the target of anti-discrimination and LGBTQI+ advocates.

Albanese is trapped in what looms as binary politics – between religious education and anti-discrimination demands over sex and gender. A fortnight ago, Albanese said he would proceed only with bipartisan support from the Dutton-led Coalition – that is not going to eventuate – but this week Albanese raised an alternative option of working with the Greens to achieve the legal changes.

This ignited a political fire alarm across religious education institutions. That’s because the recent release of the Australian Law Reform Commission final report on religious exemption from anti-discrimination law is widely seen within the sector as a far-reaching assault on religious freedom and parental choice.

Delaying this bill is an existential issue for religious education. On the opposing side, progressives and the LGBTQI+ lobby insist that Labor must honour its past pledges and implement the ALRC recommendation to remove the religious entitlement to discrimination against staff and students on the basis of sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, marital or relationship status.

If Albanese sticks by his bipartisan position, the likely upshot is that nothing happens because bipartisanship is not available. That would be an ignominious retreat by Labor, a broken promise and inflame sentiment particularly within the LGBTQI+ community because there is a progressive majority in the House of Representatives and the Senate – which means the numbers almost certainly exist to amend the Sex Discrimination Act along the lines recommended by the ALRC and wanted by the LGBTQI+ lobby.

This is a moment of high danger for religious education and for the Catholic school system in particular, given it constitutes the overwhelming majority of both non-government and religious schools. Catholic schools enrol one in five Australian students, totalling 805,000 in 1756 schools.

The danger is highlighted since the ALRC recommendations were shaped by the terms of reference set by Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus. It is assumed, therefore, to reflect Labor thinking. The 469-page ALRC report looms as a legal turning point and a historic threat to the operations of religious education in Australia.

Albanese’s reach-out to Dutton on bipartisanship means only one thing – he wants religious freedom off the agenda and fast. His message seemed to be: let’s work together or I’ll ditch it. That also means abandoning the related bill and alienating the LGBTQI+ lobby that Albanese has cultivated all his political life.

As the stakes increase, there are belated signs religious education authorities, including the Catholic sector, are ready to display some political muscle. The Catholics have long shunned political conflict given their disgrace over the extent of child sexual abuse but their resulting loss of clout, particularly within the ALP, has been conspicuous.

While opposition legal affairs spokeswoman Michaelia Cash has been given, in confidence, Labor’s proposed legislation from Dreyfus, the expectation is that Labor’s proposals closely mirror the ALRC report. If accurate, the idea that Labor has drafted legislation along these lines and has the numbers in parliament to secure its passage is a potentially alarming event for religious education.

Any idea Labor would team up with the Greens to legislate these changes seems improbable. The Greens’ platform is hostile both to religious education rights and government funding of private schools. Any such collaboration would be a transforming event for Labor. Albanese’s reference to the Greens was probably a tactical ploy and his remarks were qualified. The PM said: “There are two pathways, either with support from the Greens or with support for the opposition. We are concerned about all forms of discrimination. If the Greens are willing to support the rights of people to practise their faith, then that would be a way forward, but we don’t currently have that.”

Earlier this week, Greens justice spokesman David Shoebridge said the party had “only one set of interests” in trying to negotiate an outcome. “It’s about protecting queer and trans kids from being discriminated against at school.”

Last week, 41 religious and education leaders wrote to Albanese opposing any negotiations between Labor and the Greens.

Referring to the Greens’ position of stripping funds from non-government schools that preference students or staff on a religious basis, the leaders said: “Based on this record, we expect that any proposal supported by the Greens will be unfavourable to faith communities. If the government chooses to abandon attempts at bipartisanship and work with the Greens, it will be interpreted by our faith communities as a betrayal of trust.

“We expect you to uphold your election commitment to maintain the right of religious educational institutions to preference people of their own faith and not to compromise this to secure the support of the Greens.”

The signatories include the Catholic Archbishop of Melbourne, Peter Comensoli; Catholic Archbishop of Sydney, Anthony Fisher; head of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of Australia, Archbishop Makarios; president of the United Shia Islamic Foundation, Hussein Faraj’ chief executive, Australian Jewish Foundation, Robert Gregory; Hindu Council national vice-president Surinder Jain; and Bishop Michael Stead from the Anglican Diocese of Sydney.

Cynics say the elemental judgment for Labor is assessing who might do the government the most damage – an angry gay lobby or an angry religious education lobby.

The paradox of this saga is that the legal opinions to the religious education communities make clear the sum of the two bills – a new religious discrimination act and removing exemptions from the Sex Discrimination Act – leaves religious education in a significantly diminished position.

This was obvious in the response of the National Catholic Education Commission to the Law Reform Commission report, with NCEC executive director Jacinta Collins saying its impact would be to “severely limit the ability of faith-based schools to operate and teach according to their ethos”, with her calling upon the government to uphold its commitment to religious freedom.

In repudiating the ALRC recommendations on faith-based education, Archbishop Fisher said “if implemented they would undermine the freedom of parents to choose such an education for their children and the freedom of religious groups to offer them that option”. Fisher said it was confounding the ALRC final report proposed even greater restrictions on religious schools than its much criticised interim report.

Labor, of course, will be anxious to deny and conceal the net impact of its bills. Despite Albanese’s pledges about religious freedom, the institutions would be worse off. This just fuels momentum against Labor and is another reason Albanese’s strategy of retreat probably makes sense.

The ALRC report is front and centre in this issue. While it says its aim is to maximise human rights, it concedes some rights are being restricted. What are these rights? The report describes them as “the freedom to manifest religion or belief in community with others and the associated parental liberty to choose an education for one’s child in conformity with one’s own religious or moral convictions”.

Albanese is supposed to be upholding these rights yet the report on which the Dreyfus legislation is based explicitly says they are being diminished in Australia. In offering a justification for the diminishing of these rights, the ALRC says the “limitations would be justified under international law as a necessary and proportionate means of promoting other human rights”.

De-coded, religious education, its communities and parental discretions would be weakened long-term. Is this what Albanese wants in an election year? For a prime minister who aspires to unite the country, it would represent a sharp edge of division. The relevant question becomes: at what point would religious educational authorities decide they had no option but to mobilise their numbers politically against a Labor government seeking an unprecedented winding back of their capacity to perform their religious education mission?

When Dreyfus tabled the ALRC report he said it was “advice to government” and not a “report from government”. But where does this leave Albanese? If Albanese presses ahead with the ALRC recommendation he will trigger a fearful political dispute going to the issues of moral and political rights – surely a mistake when the public is focused on cost of living.

Asked by Inquirer, Cash said: “Our guiding principle is that any religious discrimination legislation should take faith leaders forward, and not backwards.” That’s the pivotal point – the Liberals see Labor’s proposals as undermining religious education.

“Having seen the proposal the government has put forward, it is clear there is a long way to go,” Cash said.

“We will work with the government in good faith on this issue.”

Opposition Leader Peter Dutton previously said he had held two private discussions with Albanese where the PM “made it clear he wasn’t going to support the religious discrimination proposals put forward by the government unless there was a bipartisan position, and also that the Prime Minister wouldn’t support any committee process around this issue, which is quite remarkable in itself.”

Dutton gave Albanese no commitment. Cash has attacked as “bad process” the extraordinary claim by Albanese that if he brings forward these contentious bills he wants them passed without a parliamentary inquiry. Indeed, that suggests a fatalism to get them off the agenda, one way or another. Trying to blame Dutton for not supporting bills that are anathema to the religious education sector is a nonsense.

The ALRC report is a “red line” for much of the Coalition. The idea that Dutton would seriously flirt with its recommendations is easily dismissed. Opposition education spokeswoman Sarah Henderson told Inquirer: “The families of 1.47 million students who attend a non-government school have every reason to question Labor’s commitment to an education system which values parental choice.”

The opposition, in fact, is playing both sides of the fence: it calls upon Albanese to honour his election commitment to religious authorities fully aware the bipartisanship he seeks is not going to happen.

Religious schools don’t need all the protections via the exemptions they enjoy in section 38 of the Sex Discrimination Act but the ALRC report seeking the removal of this section leaves them vulnerable. Their legal ability to require staff to live in accordance with the tenets and beliefs of their faith is seriously limited.

Jacinta Collins, speaking for the Catholics, said: “Catholic schools are not seeking the right to discriminate based on personal attributes but rather to maintain their religious identity and mission. The current exemptions are designed to ensure that discrimination legislation doesn’t impinge on religious freedom and enables faith-based schools to continue to build a community of faith by preferencing the employment of individuals who share and support the ethos and mission of our schools.”

The NCEC submission highlighted a 2021 survey showing 63 per cent of the general population, 82 per cent of Catholics and 79 per cent of Catholic school parents believe religious schools should be entitled to require employees to act in ways that uphold the values of that faith and the school is entitled to favour hiring employees who share those values.

On the other hand, the ALRC report rejected arguments that if students were allowed to embrace “lifestyles that contradicted the beliefs of the community” then schools would lose their religious authenticity. Its recommendations meant it would be unlawful for schools to engage in direct discrimination against a student proposing to form a gay club.

An authority on discrimination law, Mark Fowler, said: “The Sex Discrimination Act and the Religious Discrimination Act are covering different legislative terrain. The Religious Discrimination Act cannot offer protections against claims of discrimination made under the Sex Discrimination Act.”

The point is the two bills are tied together politically but are not legally dependent on one another.

It may be that religious education decides the status quo is the best outcome it can get from this political mess. It would mean that the prospect of a bill to protect religion in Australia was seen, again, to be too hard. That would constitute a failure of our politics and parliament. At the same time, the LGBTQI+ community would be left frustrated in having failed to win reform of the Sex Discrimination Act.

Fundamental to the dilemma is the mindset of the ALRC, which should have tried to navigate a way through these competing interests and failed to do so. At a time when enrolments in religious schools in Australia are rising and parents are voting with their feet, the ALRC has brought down a report that says nothing about the contribution and importance of faith-based education in Australian history and contemporary life.

As Archbishop Fisher said, every day millions of Australians engage with Catholic health, education, welfare and parish services – institutions employing hundreds of thousands of people of different faiths and of none.

The entire debate needs to be reframed. That means a shift away from the rigid stereotype of an irrevocable clash between the right to discriminate and the right to equality. That is the challenge and, unless there is a sudden change, it still seems to elude us.

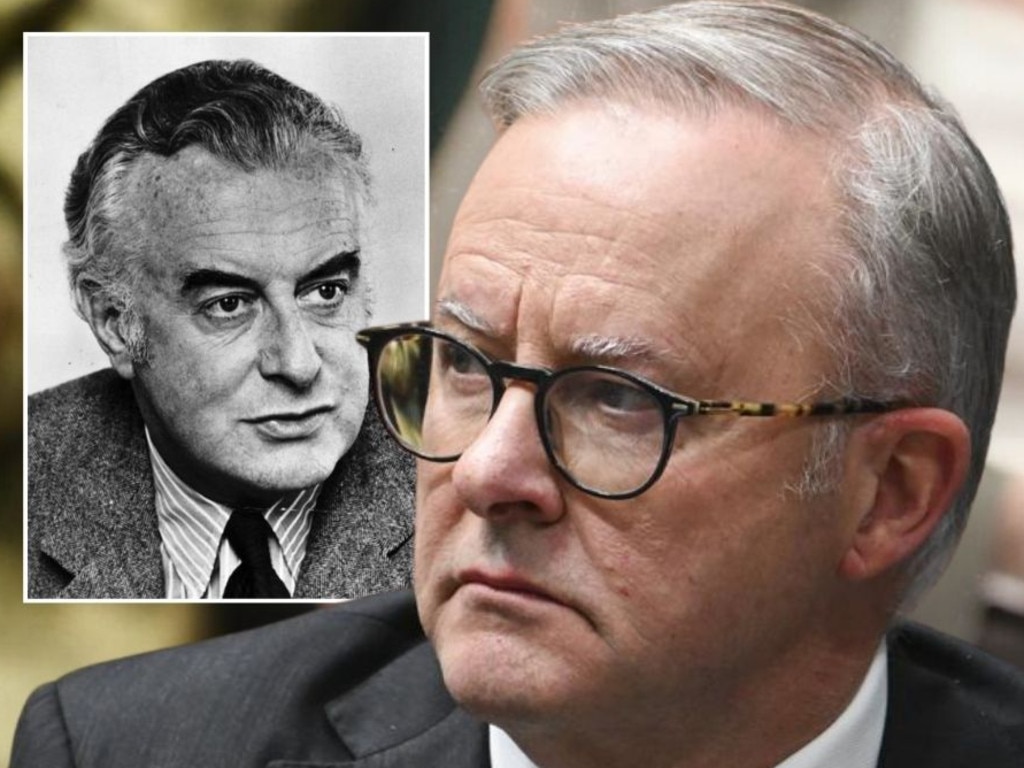

Anthony Albanese has landed himself in a revealing but difficult position with the full spectrum of religious leaders in Australia warning against any move by his government to undermine faith-based education and parental school choice consistent with religious conviction.