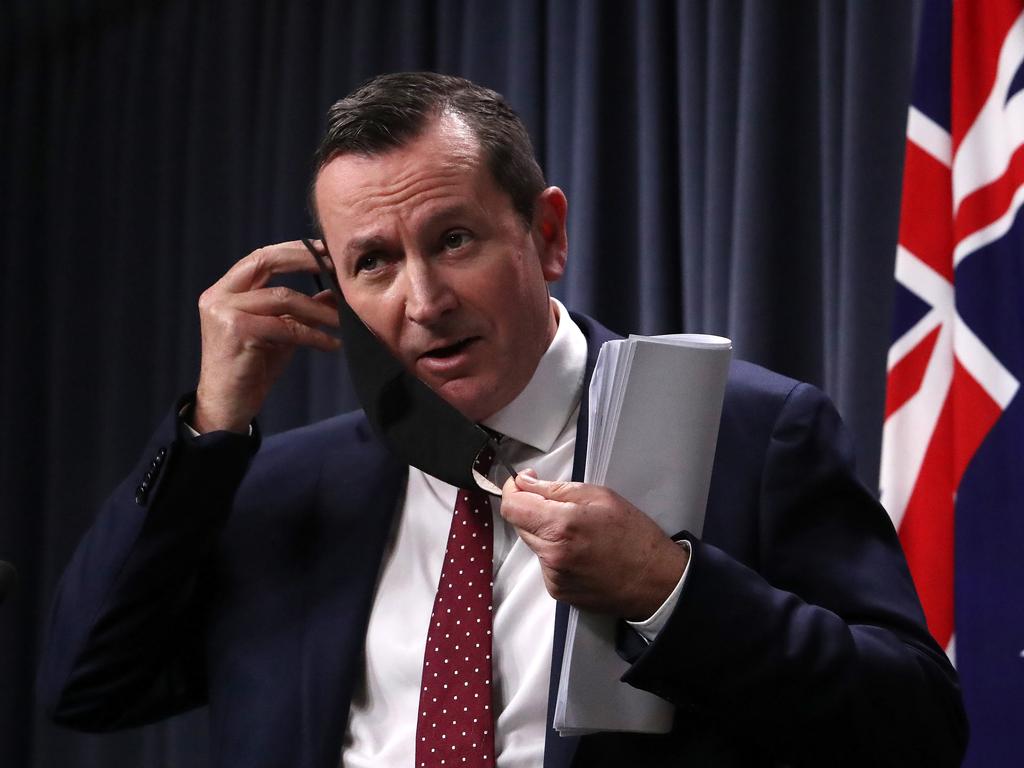

PM is under attack from left and right

Scott Morrison faces as lurking menace on the populist right that has two targets in their sights.

Morrison has drawn a line in the sand. The consequences will be decisive. “We are not seeking to mandate vaccines,” Morrison said.

“That is not the government’s policy. That is not how Australia has successfully run vaccination programs in the past.”

Of course, there are special exemptions arising from vulnerabilities in aged care and quarantine. But Morrison, as PM, has a medical obligation to the nation.

With vaccine hesitancy varying widely in surveys from 10 per cent to a touch above 20 per cent, the voluntary principle faces certain pressure on grounds of public health, social responsibility and popular opinion.

The higher the vaccination, level, the more certain lockdowns can be averted. Get the picture: vaccination rates will determine your lifestyle and your freedoms.

This issue will provoke conflict over law, safety and governance. Morrison stands by tradition and what he likes to call “the Australian way”.

He stands for voluntary vaccination, and he must prove in coming months that it works. He told parliament he won’t demonise people and he won’t set Australians “one against the other”.

However, the principles are compelling and in conflict: business feels obliged to protect the health of employees by vaccination, yet individuals choosing not to be vaccinated invoke their right not to be discriminated against. Yet that right must now come with a higher price – individuals taking that option must realise they cannot enjoy all the privileges they once did because of the danger to public health.

And companies must walk a fine line, being advocates for vaccination but stopping short of heavy-handed duress that provokes an industrial relations row.

Business Council of Australia chief Jennifer Westacott said employer action must be based on preventing health risk, not as a means to get to 80 per cent vaccine coverage – a key distinction.

Morrison will lose the next federal election unless he can hold the political centre together. Yet it risks being further battered on three issues: constant lockdowns in the suppression phase; vaccination that must find the right balance between freedom and responsibility; and climate change action as proof of energy restructuring.

There is a motley crew forming far on Morrison’s right keen to run harder than ever against lockdowns, champion medical freedom and repudiate “net zero” at 2050. While the Labor Party’s attacks are damaging Morrison, there is also a lurking menace on the populist right that could bring him undone.

Clive Palmer is rattling the cage, attacking both major parties, opposing lockdowns and threatening the government with legal action if it takes any action to mandate or incentivise vaccines.

Pauline Hanson is a public menace – she refuses to be vaccinated, makes outrageous and false claims about vaccines, says people have got a right to catch Covid and die, and denounces lockdowns.

Former Queensland premier Campbell Newman has quit the LNP and is running as a Liberal Democrat, claiming that the nation is “poorly led” and that Morrison engages in “illiberal big government overreach”.

Managing such stances – laughingly branded as conservative – is a permanent job for every Liberal leader. More often than not, the threat is exaggerated. Palmer, Hanson and Newman carry loads of political baggage and are largely discredited. Yet their ability to leverage conservatives at the margin, win significant backing from high-profile media commentators and reinforce the Labor message – that Morrison is failing as a leader – should not be discounted.

The risk for Morrison, as he seeks to hold the political centre, is that the narrative of the conservative populists will undermine his base.

Many of his opponents on the right have two targets: first Gladys Berejiklian, and second Morrison. But the state to watch is Queensland, always the point of maximum susceptibility to populism and prone to sudden electoral movement.

The trade-offs Morrison confronts are diabolical. He must maximise vaccine coverage to reach 80 per cent as fast as possible without an ideological war over freedom and mandating – and at the same time he must harden up Australia’s “net zero” at 2050 without fracturing the Nationals and ruining the Coalition’s position in the regions.

This week’s release of the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change merely highlights that time is running out for Morrison and Nationals leader Barnaby Joyce to sort out this policy and political agony.

In a sense, it is strategically easy. Australia has no option but to embrace “net zero” as a 2050 target. The financial and investment community will impose this on the country. Morrison knows this and keeps saying it.

The Nationals can either seize the opportunity to govern the terms and conditions of how Australia gets there or live with the decisions imposed by a future ALP government.

What sort of a choice is that really for the Nationals? They need to decide if they are a party of government. That’s the issue here. It means confronting the actual problems that Australia faces.

The sooner Joyce can terminate his dual political identity, the better. He is the Deputy Prime Minister, but on this subject he talks like a blow-in just visiting Parliament House. “You must lay down the plan,” he told the ABC this week. “Nobody can tell us what’s involved in the plan.”

At his media conference after the IPCC report, Morrison said: “Financiers are already making decisions regardless of governments. I want to make sure that Australian companies can get loans. I want to make sure that Australians can get finance. I want to make sure that our banks will finance into the future.”

Exactly. Too many of the politicians have the deluded view they have the power to make these climate change decisions. But that power is being taken from them, as Morrison made clear.

The Nationals may hate the world that has evolved but it’s the world the Nationals must live with. And right now, they have a powerful bargaining position. This is because of the expectations Morrison has raised about any new government plan.

Consider his assurances: there will be no blank cheque; the cost of any 2050 target will be laid on the table; the government will rely on technology not taxes; there will be no targets without plans; people in the regions will not be asked to carry the national burden; the plan will set out the jobs and industries to be supported by new technology; and the whole country will be brought along.

If Morrison is true to his word, this will be a plan and a half. Yet the politics will be daunting. If Morrison and Joyce seal the deal – authorised by the Nationals partyroom – how will the Nats manage the backlash in their constituency? Imagine how Joyce’s words about not buying any 2050 deal would be put up in lights and turned against him.

Yet if Morrison cannot seal the deal, then he has a leadership problem: a Liberal PM who had to bow before Nationals climate resisters. What a gift for Labor, the Greens and the progressive media to use against Liberal MPs in the capital city suburbs.

Ever since the 1996 election,

the lesson of conservative politics under every Liberal PM – John Howard, Tony Abbott, Malcolm Turnbull and now Morrison – is that disruption and breakaways on the right are the ultimate threat.

Morrison won the 2019 election essentially because he held together the potentially fracturing Coalition vote that spans the urban centres and suburbs of Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, along with the regions and the big mining states, Queensland and Western Australia.

The key to the Coalition’s success election after election has derived from its superior ability to appeal across the spectrum of Australian life and geography.

This has been Labor’s weakness. But the task facing Morrison in holding this broad constituency together becomes more challenging because of Covid-19 and climate change.

Morrison now tries to turn his mistaken remark about the vaccine rollout not being a race into a plus. “We’re going to run the race all the way to the finish line,” he says now.

The PM’s political assumption is that the world will look different in 2022; the nation will be vaccinated, 30,000 lives will have been saved, and a million people will be back in jobs. But that depends how on the Delta variant is managed. And that has a long way to run.

Queensland backbencher George Christensen is not a candidate at the next election but his voice still resonates with ideological clarity. This week in parliament he declared: “Restore our freedoms! End this madness!” Christensen said masks didn’t work, claimed lockdowns “don’t destroy the virus”, attacked vaccine passports as “a form of discrimination”, and said while people would die we must never accept “the systematic removal of our freedoms.” He attacked the “media elite” and “dictatorial medical bureaucrats” for spreading fear.

When Opposition Leader Anthony Albanese moved a motion against Christensen, Morrison was fast enough to accept the motion, endorse it and speak to it. He attacked vaccine misinformation – the “crazy rubbish conspiracies” – but declined to mention Christensen, for the obvious reason identified by Joyce the next day: the government has a paper-thin margin on the floor. Grievance stalks the country in these days of lockdown. And the scale of grievance is mounting. Morrison seeks to hold the Team Australia ethic together but the political climate is polarising.

Perhaps the polarisation is near a peak and will fade, providing the vaccine rollout proceeds successfully and reaches a high coverage on a voluntary basis.

Morrison made clear this week he would not legislate to sets the terms of vaccination by business. That was the right decision. Just imagine the upheaval in the Senate if he had tried. But the strong message from the PM is that conditions surrounding vaccination are the job of state governments and state health orders.

It’s the old story – the premiers are still in change.

But Morrison will face pressure from both business and unions to play a strong role in setting the vaccination guidelines. Westacott has complained long and hard about the lack of national consistency in the public health orders covering lockdowns and essential workers. She told Inquirer unless there was greater consistency on the critical issues of vaccination, the risk was the country would be forced back into more and more lockdowns.

Morrison is taking an arm’s-length, cautious stand. But he needs to beware. If he remains distant and there is confusion, he will be blamed.

His critics will make the accusation of another example of Morrison not taking responsibility and shifting the blame.

The reality is that business and institutions have a duty obligation to ensure workplace safety as a public health obligations.

High vaccination rates – the pathway to Australia’s relief – now come with fresh political and philosophical challenges for Scott Morrison as conservative values rub against public health responsibility, triggering another test of his leadership.