Peter Reith was at the centre of the most contentious Howard-era changes

The one-time deputy Liberal leader was a driving force behind the Fightback! agenda, the GST and the revolution on Australian wharves.

On March 3, 1993, Mike Willesee settled behind his desk as host of A Current Affair. His guest, John Hewson, was the leader of the opposition who hoped to be prime minister in 10 days. Polls strongly suggested he was on track to defeat Paul Keating’s Labor government.

Willesee was to ask Hewson about his Fightback policies, with which the Liberals would radically reset the economy by introducing a GST. After intense pushback from various groups, the Liberals recast the policy to exempt food.

Famously, Willesee’s opening question was: “If I buy a birthday cake from a cake shop and GST is in place, do I pay more or less for that birthday cake?”

The prime-minister-in-waiting’s baffling, drawn-out response proved fatal. It is one of the most mocked moments in politics: “If it is a cake shop, a cake from a cake shop that has sales tax, and it’s decorated and has candles as you say, that attracts sales tax, then of course we scrap the sales tax, before the GST is …”

But for a partyroom vote three years earlier – when Hewson defeated Peter Reith for the Liberal leadership – it would have been Reith answering that question. The experienced Reith was likely to have done so more successfully, not least because Hewson’s more experienced deputy was shadow treasurer and had co-authored Fightback.

The so-called “unlosable election” might have remained just that and Reith could have been sworn in as our 25th prime minister. He might have performed well, but an achilles heel was that, unlike most ambitious politicians making decisions with one eye on policy and another on polls, Reith was focused on results. He was undoubtedly a successful minister, but not all his victories were unalloyed.

Before winning government in 1996, John Howard had promised reforms to help streamline industrial relations, making workplace bargaining less subject to the outside influence of big unions with the introduction of Australian Workplace Agreements, among other changes.

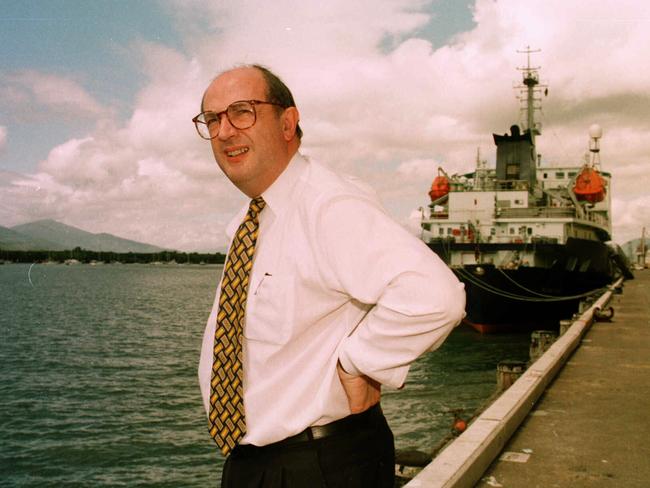

By then, Reith was Howard’s minister for workplace relations and he was prepared to take risks when others would not. That was how he came to reform Australian wharves in 1998 with an attempt at an industrial revolution from which his predecessors had cowardly recoiled since World War II. In a confrontation invested with terrific risks – and almost identical to Rupert Murdoch taking on the London print unions in 1986 – Reith became a figure of hate but ultimately prosecuted the cause. Productivity on the docks soared while costly industrial action shrank.

It is easy to be brave from a distance, but Reith sat at the dispute’s epicentre. Not for the first time did he lose a few friends; that was never in his thinking. And it was why he could so easily brush away the inflammatory comment by ACTU secretary Bill Kelty comparing the wharf dispute with murderous Nazism.

Reith was born in Melbourne and attended Brighton Grammar, an upmarket Anglican boys’ school whose catchment includes Melbourne’s wealthy bayside suburbs, but still tends to produce more footballers than politicians.

After completing law and economics degrees at Monash University he worked in Melbourne before moving to then sleepy Cowes, 140km south of the capital on Phillip Island. He had strong connections there: his grandfather, Albert Sambell, an engineer, had been the first president of the Phillip Island Council and was responsible for its early development. (An uncle, Bill Sambell, rowed for Cambridge in the universities race at Oxford, winning in 1934 – a team member was actor Hugh Laurie’s father – and was also selected for the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics. The sporting gene bypassed Reith.)

He was soon immersed in the island’s community and became president of the local Liberal branch. In 1976 he was elected a councillor for the Shire of Phillip Island, and that October began talks that led to the establishment of the Newhaven School there. It opened doors to students in January 1980.

He contested and won Liberal preselection for the federal seat of Flinders in 1982 when the unwell Liberal deputy leader Phillip Lynch retired (he died in 1984). This set off an unprecedented series of events in which Reith ran for the seat three times in less than two years against three different Labor candidates.

He beat Rogan Ward in the by-election. But on the day he arrived to be sworn in and take his seat in Canberra in February 1983, he was “greeted by the sight of the secretary to his excellency the governor-general fixing on the doors of the house the proclamation of the dissolution of the 32nd parliament”.

Reith lost Flinders to Labor’s Robert Chynoweth in Bob Hawke’s landslide victory weeks later. By the time of the next election in December the following year, Chynoweth had moved to contest the new seat of Dunkley, and Reith won narrowly against Labor’s Russell Joiner. He represented Flinders for the next 17 years.

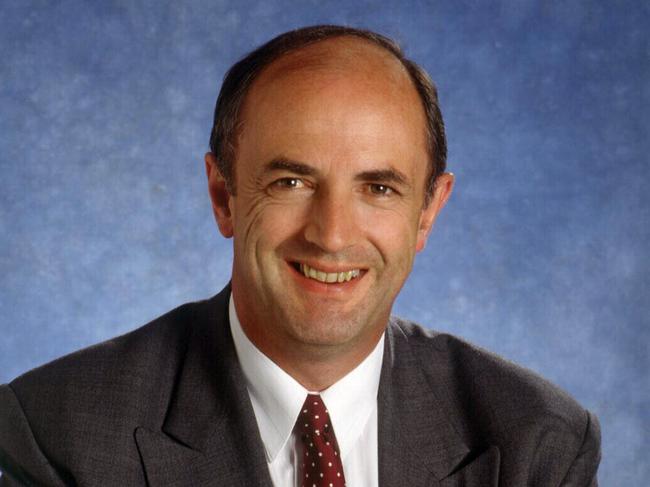

He was a shadow minister for almost 10 of them, including being shadow treasurer when budgets were brought down by three Labor treasurers – John Kerin, Ralph Willis and John Dawkins – in successive years. His shadow portfolios included housing, sport, defence and foreign affairs and he was deputy leader of the Liberal Party.

When the Liberals won government in 1996, he was set the task of implementing Howard’s industrial relations agenda. All parties – the government, unions and employers – understood what this would involve.

For decades Australia’s waterfront had been notoriously expensive, strike-bound and inefficient. It wasn’t that it was out of control, according to Chris Corrigan, the managing director of stevedoring company Patrick; it was just that the Maritime Union of Australia had control.

In 1997, Corrigan had secret talks with the government about his radical plans and to seek support. The details are disputed, but Howard and Reith were on board. In April 1998 Corrigan – having trained an alternative workforce in Dubai using many former defence force personnel, news of which leaked out – sacked his 1400-strong workforce.

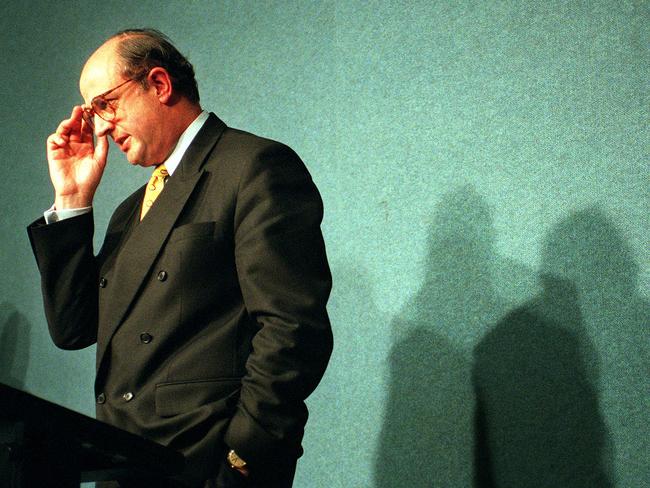

The element of surprise was deflated and the MUA was ready for war, but its members had never assumed they’d be fighting from outside the gates, watched over by dogs and gorilla-sized security guards, faceless behind black balaclavas. An overconfident minister weighed in days later: “These former Patrick employees are not going back to Patrick,” Reith confidently told Laurie Oakes.

Inevitably, it ended in court. The MUA won in the Federal Court, and again when it was appealed there. It then went to the High Court which also decided in favour of the union, but with vital modifications benefiting the employer.

At this stage, Reith spoke to his prime minister: “He came to see me one night at Kirribilli House,” Howard remembered on Tuesday. “He said ‘I am prepared to resign if you want a sacrificial lamb’, and I said ‘Not on your life, I can’t afford to lose you’.”

In any case, the episode was hardly a loss for the government, or for the country.

The negotiations with Patrick to settle the dispute halved the workforce, introduced longer hours, more casualisation and leaner work crews and gave the company control over rosters.

The other notable controversy in Reith’s time as minister was the 2001 children overboard affair. It was alleged by the immigration minister, and repeated by others including Reith, that illegal immigrants about to be intercepted by HMAS Adelaide off Christmas Island had thrown their children into the sea, in the belief they would be picked up by the ship and taken to Australia.

It wasn’t true, and the dodgy photographs to support the claim were dismissed along with the allegations at a Senate select committee. It damaged Reith and the government, but Reith defended himself in an interview with Channel 9 in 2015: “All the criticism of me is that I was running some sort of conspiracy thing – that is nonsense,” he insisted. “When you’re a defence minister, you’re based in Canberra.

“You’ve got no idea what’s going on up north on the seas.

“You take the advice you get from the top bloke and that’s what I did.”

Perhaps he had appointed the wrong “top bloke”.

Apart from being leader of the house, Reith also served as minister for small business.

Former prime minister and colleague Tony Abbott says Reith was “one of the big figures who made the Howard government so successful”.

Abbott described Fightback as the boldest manifesto ever produced by an opposition and that, despite it being dubbed the “longest political suicide note in history”, it had subsequently been implemented by both sides of politics.

“He was the architect of the Howard government’s first round of workplace reforms – the one that caused productivity and real wages to substantially increase – not the later Work Choices changes that were thought to have gone too far and that helped cause Howard’s defeat in 2007,” Abbott says.

Abbott says that in Howard’s early years Reith “was seen as a rival to Peter Costello as Howard’s potential successor. If so, it was an honourable contest that never involved either leaking against the other or the incumbent PM.”

He says Reith belonged to an era when policy debates were robust and policy changes could be transformational – “an era of bigger, better political characters”.

When Abbott became Reith’s junior minister in the employment portfolio between 1998 and 2001, “he told me that he’d give me full autonomy to do what I thought best … but that if I stuffed up, I’d wear the blame! I could not have asked for a better colleague and regarded him as a kind of elder brother in public life.”

Howard describes Reith as a tough, intelligent and persistent minister, adding that “gutless people” in the business community had insisted government act on the waterfront problems, “but as soon as we did something about it they got nervous. The two heroes of that dispute were Peter Reith and Chris Corrigan.”

Over decades “both sides of politics tried what you might call the consensus approach”, he adds. He and Reith were surprised to fail in the courts, but “what the High Court did was to say (that) forcing Patrick to take back its entire workforce would impose an unreasonable burden on Patrick, and that was the way in which the High Court in effect forced Corrigan and the MUA to negotiate”.

Howard says Reith was always committed to market-based reforms.

“He was hardworking and incredibly courteous … and a very objective thinker,” he says.

When the Liberals failed against Hawke again in 1990, Howard had already had a stint as opposition leader.

Reith, ambitious himself, approached Howard with the news that the party wished to move on: “Look, John, you can forget about any idea of coming back.”

“He knew that was not what I wanted to hear,” Howard remembered with amusement.

“That’s what I respected about him.”

Peter Reith, lawyer and politician. Born Melbourne, July 15, 1950; died Melbourne, November 8, aged 72.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout