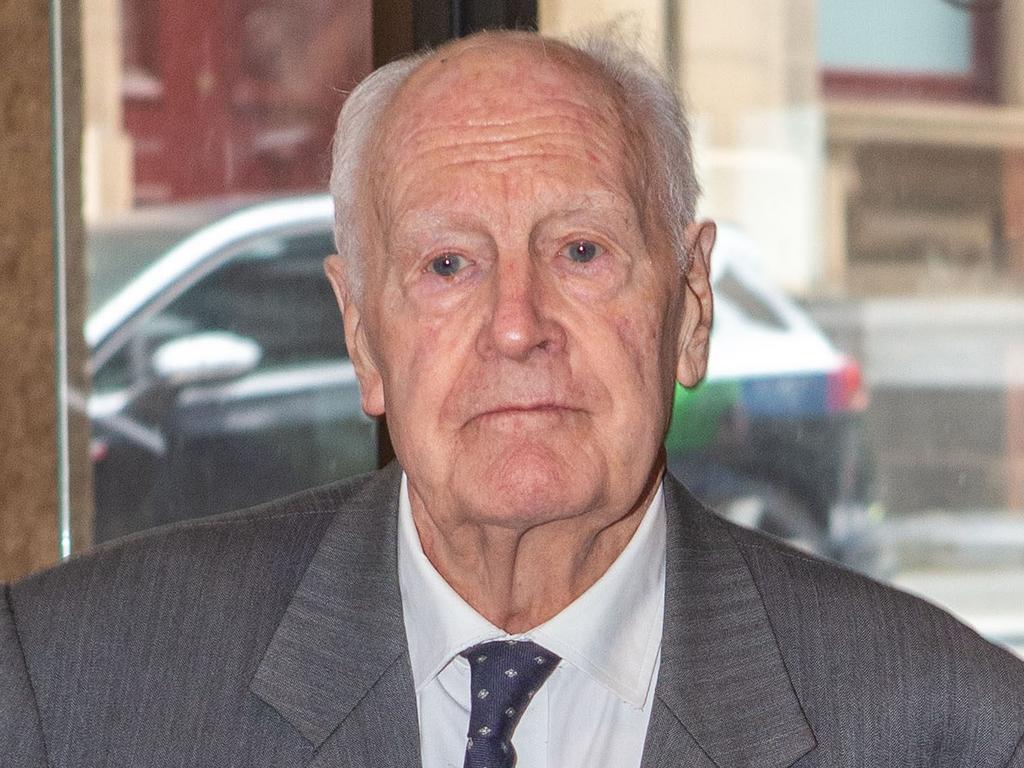

Peter Hollingworth, the Anglican Church and a long fall from grace

Critics say the Anglican Church is on trial as much as the former governor-general, who is still fighting to protect what is left of his reputation.

People who have been important to him, down to more mundane matters such as presents, birthdays and a reference to an anniversary.

Gentle reminders for an ageing but still active mind as, two decades on, 87-year-old Hollingworth is still fighting to protect what is left of his reputation after being forced out of Yarralumla in 2003 over his mishandling of the child sex abuse scandal in Queensland in the 1990s.

Hollingworth this week faced the Anglican Church in Melbourne’s Professional Standards Board, which must decide whether to punish the former archbishop of Brisbane for his at times grievous mistakes and decision-making.

He is facing 10 allegations of misconduct relating to four sex offending members of the Anglican Church and school system in Queensland under the notoriously secretive independent system adopted by the church in Melbourne and presided over by former barrister Robin Brett KC.

Hollingworth will learn, probably within weeks, whether he will be defrocked, lose the right to officiate or simply be admonished or, indeed, face whatever penalty the board sees fit.

Losing holy orders is on the table but not at all guaranteed, the tribunal’s effective prosecutor not having apparently called for this sanction, although the church legislation seems to leave wide open the options for punishing misconduct.

Hollingworth remains a bishop of the Diocese of Melbourne, where he lives, and has reaped millions from taxpayers through his pension and entitlements as a former Australian head of state, with attempts revived this week by the Greens to have the system overhauled to enable payments to end for serious misconduct by any former G-G.

Some of Hollingworth’s mistakes include failing to act on expert advice regarding a notorious sex offender and allowing him to stay with the church, casting inappropriate aspersions on a victim of sex abuse, failing to protect victims of abuse at a Brisbane school and writing an inappropriate and insensitive letter to a victim’s brother while overseeing a scandalous church response to the abuse crisis.

The four abusers named in the Melbourne complaints are believed to be the late bishop Donald Shearman, former rector of the Dalby parish John Elliot, Toowoomba serial abuser Kevin Guy and former teacher Kevin Lynch, who was a prolific pedophile at Brisbane schools.

Hollingworth’s rhetoric on the broad issue while archbishop and then governor-general was at times judged as clumsy and hurtful, his friends arguing he was placed in a job that did not necessarily fit his skills set.

In short, he made a disastrous career choice.

Having been a high-profile social justice campaigner as the head of the Brotherhood of St Laurence from 1980-89, Hollingworth became (inexcusably) bogged down in the fight by lawyers and insurers to save the church’s coffers after being appointed archbishop in 1989.

Ignorance of the effects of child abuse has never been valid; at the Brotherhood he would have been confronted daily with the impact of abuse on families across the country.

Almost 1100 people alleged they were sexually abused as children in Anglican Church institutions nationally, according to the child sex abuse royal commission, with almost 570 alleged perpetrators identified in the report, nearly 250 of them ordained clergy.

Serious errors

Hollingworth, who uses a walking stick, cannot run from his past.

For five years the Anglican Diocese of Melbourne, through its various related entities and independent investigations, has been grappling with the large volume of evidence against him, much of which is already on the public record and been pouring in from complainants in relation to his time as archbishop.

The process has been clumsy, already failing key tests, principally the need to deal swiftly with sex abuse-related allegations to minimise the retraumatising of victims and being cloaked as it is in secrecy.

Survivors have complained of a dearth of communication between them and investigative bodies.

One complainant said this week they are still waiting to be told whether the tribunal is on, saying they “haven’t even heard from them since 2021”. This is despite believing they were a complainant.

The five-year delay between complaints being received against Hollingworth and this week’s hearings are a source of embarrassment for the church in Melbourne. Hollingworth, it is believed, did not know for several years what was being alleged.

While Hollingworth is ferried around Melbourne in a black, 6-series BMW, owned by the commonwealth, the church leadership has been facing heat over what is a multimillion-dollar response to the sex abuse royal commission.

“They still protect their own rather than the survivors,” anti-abuse campaigner Hetty Johnston says of the church. “As such they’ve failed to rebuild trust.”

It is six years ago on Monday since the sex abuse royal commission found Hollingworth had made a serious error of judgment by allowing John Linton Elliot to continue in his ministry even though he had admitted to child abuse. Hollingworth’s behaviour over Elliot remains one of the most reckless acts of any clergy in the past 30 years.

Melbourne’s Professional Standards Board will have in its files a letter from November 30, 1993, in which Hollingworth shows knowledge of Elliot’s behaviour and knows the medical advice is that he is a high-risk offender but then lets him keep his job. Hollingworth, the company man, backed the sex offender.

“The matter which has exercised my mind most strongly is the fact that your departure at this stage could cause unintended consequences that would make things worse for you and the church,’’ he wrote to the criminal priest.

“The major difficulty is that in not taking disciplinary action I and the church could subsequently be charged with culpability while at the same time an act of removing you would place you in an impossible situation at your age and stage in life.’’

Hollingworth admitted during the royal commission process that he had examined his conscience and had a greater understanding of the long-lasting effects of child abuse.

“The more I’ve learnt about the long-term effects on survivors of sexual abuse, the better I understand the importance of how the complaints are dealt with,” he said.

The nemesis

In many ways, Beth Heinrich has been Hollingworth’s nemesis.

Heinrich, now in her 80s, was sexually abused from the age of 14 by the late Anglican priest and bishop Donald Shearman, and Hollingworth was reported by the ABC as saying she had encouraged that abuse.

(He contests the reporting, arguing that he was referring to a later period when the relationship started again, both as adults. Either way, it reflects badly on Hollingworth, given Heinrich’s decades-long battle with the effects of the child abuse she suffered.)

“Dr Hollingworth regrets making the comment but he did not say what the ABC said he did,” his lawyers wrote to the national broadcaster this week.

The inquiry is also believed to have heard argument this week about the role Hollingworth played in a failed mediation in the 1990s involving Heinrich’s abuser.

Heinrich, many years his junior, said Shearman had formed a sexual relationship with her when she was sent to a church hostel. A storm was created when Hollingworth was reported saying: “There was no suggestion of rape or anything like that; quite the contrary. My information is it was rather the other way around.”

Heinrich, as much as anyone, has kept piling on the pressure over the church’s handling of her case, which seems likely to head to the courts again, regardless of the board’s findings.

The Shearman abuse and the church’s response to her has had an undeniable impact on her long-term health.

Heinrich had several people supporting her this week, including lawyers Judy Courtin and Professor Gideon Boas, and UniSA adjunct professor Chris Goddard.

Goddard, a global expert on child sex abuse, is in awe of Heinrich’s resilience.

“She is just amazing,” he said after Heinrich read her victim statement to the board.

Heinrich wrote to the tribunal last year: “Of course none of this dragged-out drama is necessary. It can easily be solved. He should find the integrity, finally do the right thing and quietly resign.”

One of the core arguments made by survivors is that Hollingworth, as a former governor-general, has profited enormously via the generous entitlements afforded to ex-governors-general but many of the church’s abuse victims have battled with compromised health and careers.

Courtin, in a submission to the inquiry this week requesting the tribunal be open to the public, estimated Hollingworth had received $12m in taxpayer-funded benefits since he stood down in disgrace in 2003. Successive federal governments have been lobbied to remove Hollingworth’s entitlements with no success, and the Greens have now reinvigorated attempts to give parliament the power to remove the largesse if former G-Gs have engaged in serious misconduct.

Australians have known for years many of the facts around Hollingworth’s behaviour but they will never know the full deliberations of the Anglicans’ Professional Standards Board.

Critics from the survivor community believe the church’s own complaints system is on trial almost as much as Hollingworth.

Former governor-general Peter Hollingworth was a diminished figure when he shuffled into the Victorian Bar Mediation Centre this week, assisted by a supporter and holding a bright pink clipboard with a series of dot points, reminding him of his daily life.