The cheap-money era is over, but the bills keep coming

Jim Chalmers provided few give-aways in his no-frills mini budget. But there was a gift tucked away for well-off boomers: our never-forgotten people.

But there was a gift tucked away for well-off baby boomers: our never-forgotten people, the greyest generation.

In May, Scott Morrison promised to extend the commonwealth seniors health card to 50,000 retirees on incomes of up to $90,000 for singles and $144,000 (combined) for couples.

Running scared, Anthony Albanese matched it in a nanosecond, calling it a “good idea”. It came into effect a fortnight ago.

That golden ticket will soon entitle 470,000 residents of pension age, who do not receive social security or other benefits, access to concessions for medicines, the extended Medicare safety net and bulk-billed visits to a general practitioner.

Canberra will borrow $70m to fund the lurk, but other entities will bear extra costs for discounts on electricity and gas bills, property and water rates, healthcare (such as ambulance, dental and eye care), and public transport.

The cost is not huge, equivalent to eight hours of our annual debt-interest bill, but it’s the principle that counts. Why tax workers more so well-off retirees, who have the means to pay their way and nest eggs producing tax-free income, can mooch?

Noisy, time rich and communing in the comments section, these lucky folks are forever in the acquisitive phase – and every political outfit (including Greens and teals) wants their approval because there’s so many of them. Yet, with gross debt of $900bn, more junk policy raises but a murmur. When tax receipts are running and votes are up for grabs, it’s payday: Howardism lives.

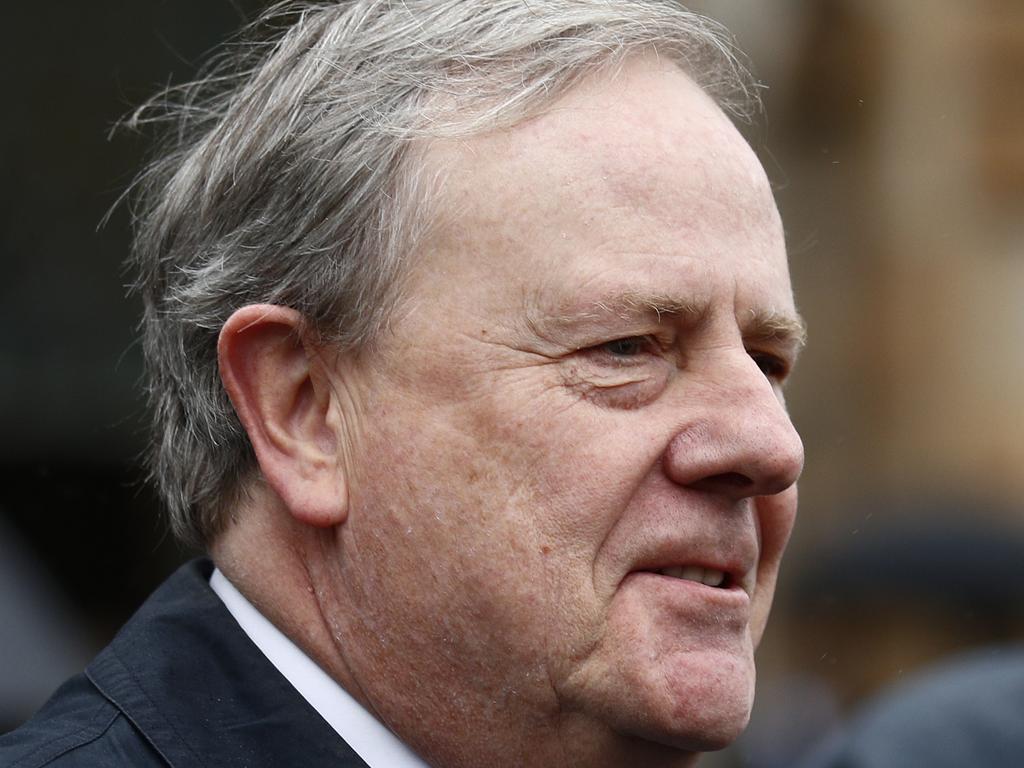

In these pages a week ago, former Liberal treasurer Peter Costello told Paul Kelly the Albanese government had abandoned the surplus strategy of previous governments. Costello alleged the political class had put up the white flag on prudent taxing and spending. “Nobody seems to think now is the time to get the budget back to surplus,” Costello said.

“Government is a lot bigger than it was 15 years ago. Tax per capita is higher and spending per capita is about 40 per cent higher. That’s a good way to measure the reach of government. But if Australia wants to maintain its competitive position it cannot have unlimited tax rises.” Every custodian lives in the shadow of the masterworks. “I mean you can’t float the dollar again, can you? Or reintroduce the GST,” a former treasurer once told Inquirer. Another lamented that tweaking the welfare system or reducing red tape never gets headlines, but such measures have a long tail of fiscal and productivity gains.

There’s also pining for another Peter Walsh, Labor’s razor-sharp waste destroyer, or his latter-day Liberal counterpart, Mathias Cormann, to put a dose of salts through Canberra or at least cut someone else’s benefit, never theirs. We’ll see whether Finance Minister Katy Gallagher is a super saver or a soft-touch enabler for Labor’s big spenders.

The truth is an ageing, middle-sized power, facing a treacherous security situation, is more expensive to run. The cheap-money era is over, but the bills keep coming. Our culture of entitlement has been liberated by the pandemic’s fiscal extravagance and we keep finding worthy, needy ways of enlarging the social compact.

Australia has voted for more of everything but, as in every other era, is resistant to the taxing or user-pays that goes with that preference, or the disruption that comes from making our economy more productive, efficient, flexible and innovative.

With deference to the revered chairman of a rival media company, Costello got hit in the arse by a revenue rainbow when he was treasurer from March 1996 to November 2007. These were the early years of our longest period of uninterrupted growth, when the world gave us a series of immense pay rises.

The larder was full. Over the dozen-year journey, receipts as a proportion of gross domestic product averaged 25 per cent. The former treasurer sold off some of the furniture, but he also scrubbed clean Labor’s red ink. Net debt was 18 per cent of GDP in mid-1996 and zero a decade later.

The first of the baby boomers turned 50 in 1996, when Costello, then 38, became treasurer. He had to contend with the 1997 Asian financial crisis and the tech wreck a few years later. Blips. There was no palpable militarisation of the Indo-Pacific, but a prime minister called John Howard, expanding the capital’s spending footprint.

Costello landed a balanced budget or surplus every year except in his first effort, climbing out of a black hole deficit left by Labor, chunkier than the one Chalmers faces today. Yet, every time revenue was upgraded because of fabulous export results, Costello struggled to keep Howard’s mitts off the bounty.

Compared with rich country peers, we didn’t do enough in the fat years to salt away surpluses. First, they should have been larger (Costello only managed a 2 per cent of GDP surplus in the year he introduced the GST). Second, he should have banked a monster-sized sovereign wealth fund the way other commodity producers had managed, not the skinny infant that is now the adolescent Future Fund he chairs.

At each election following 1998’s near-death experience, Howard showered voters with goodies: cheaper fuel, tax cuts, cash to pensioners, more public servants and endless middle-class welfare. Growth in the era’s spending is bracing: an after-inflation average of 2.6 per cent a year (not counting the 2000-01 outlier, when the GST was introduced).

“I have to foot the bill and that worries me,” Costello said about those free-spending ways in Wayne Errington and Peter van Onselen’s 2007 John Winston Howard biography. “And then I start thinking about not just footing the bill today but if we keep building in all these things, footing the bill in five, and 10 and 15 years and you know I do worry about the sustainability of all these things.”

Those 15 years are up, Chairman Pete, and there’s been a lot of permanent spending and concessions baked in during temporary revenue bursts – by you and your successors. Your GST is not fit for purpose; the tax system sub-optimal, a legacy of ill-considered fiscal moves. In 2006, Costello gave people 60 and over tax-free superannuation earnings. That brain-snap costs the budget more than $26bn a year (and its real cost will double over the coming four decades).

Tax-free super was, economist Saul Eslake said in 2011, “one of the worst taxation policy decisions of the past 20 years (and there’s a fair bit of competition for this ‘honour’, in my opinion)”. Does Costello worry about that? Or halving the capital gains tax?

Under Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard, revenue dried up after the global financial crisis. Annual receipts averaged 22.3 per cent of GDP during those two terms (a drop, year in year out, of $68bn in today’s dollars compared with the Costello coffers). In 2010-11, receipts plunged to a four-decade low of 21.3 per cent of GDP.

Still, Labor planted post-2013 spending time bombs, including the Gonski school education boost and the National Disability Insurance Scheme, which is now bigger than Medicare, and on track to cost $50bn by 2025-26.

But the greying of Australia, pandemic debt and rise of China have changed the fiscal game. At the 1996 census, there were 2.2 million Australians aged 65 and over. Put another way, there were 5.5 working-age people (aged 15 to 64) for every retiree.

According to last year’s census, there are 4.4 million people aged 65 and over; but the rise in the working age population has not kept pace. There are only 3.7 people for every retired person.

Although they’ve been debauched by politics, Intergenerational Reports, instituted by Costello, reveal the fiscal consequences of an older Australia over the next 40 years: more spending on aged care, health and medicines, less on childcare and education. Forever deficits.

Chalmers has made much of the expected revenue upgrades Labor is reserving for the bottom line. The Treasurer says he will be returning 90 per cent; the former government’s record was 40 per cent. Let’s see how Treasury’s estimates translate to the growing community desire to spend more, especially when the economy drops down a couple of gears over the next two years.

We have an annual structural deficit of $50bn over the coming decade. Taxes and user charges are set to rise. Cutting concessions is also on the table. There’s fat in the budget and public service inertia. The inferior approach would be to impose a greater burden on ordinary workers, something fiscal drag does in a stealthy way. Bracket creep never sleeps.

On Wednesday, staff from the International Monetary Fund said public debt remained sustainable in Australia. Officials pinpointed growth in spending on the NDIS, healthcare and aged care as risks to budget repair. The global lender reiterated the case for switching from high direct taxes on incomes to under-utilised indirect taxes, while compensating low-income families.

The IMF recommend broadening the GST base to limit exemptions for healthcare spending and restricting the capital gains tax exemption for the sale of main residences. It welcomed Treasury’s forthcoming analysis of the winners and losers from $200bn in annual tax concessions that will help to fortify our tax system.

No one, other than the loopy, is proposing “unlimited tax rises”, as Costello avers, just raising revenue in a more efficient, sustainable and equitable way; fixing the cheeky leaks and loopholes that allow tax planning to thrive; and taking proper account of the free riders who contribute nothing to the common weal.

Jim Chalmers provided few give-aways in his no-frills mini budget last month, honouring campaign pledges on childcare, aged care, medicines and education, with a bonus in paid parental leave.