Patient zero: How a young Norwegian sailor shipped HIV to Europe in 1962

Fifty years ago, kitchen hand Arne Vidar Roed returned home from Africa, unknowingly bringing a souvenir with him.

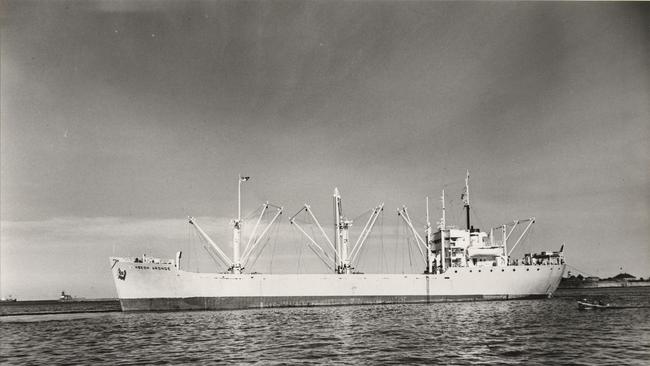

Teenage kitchen hand Arne Vidar Roed returned to Oslo from his second long trip aboard the cargo ship Hoegh Aronde in 1962, filled with stories of adventures in exotic lands, a world away from the uneventful civility of post-war Norway.

The Hoegh Aronde stopped at Dakar, the capital of Senegal; the Guinean port of Conakry; the Liberian capital of Monrovia (named after the fifth US president, James Monroe, who helped fund that project); the Ivory Coast; Ghana; Nigeria; and Douala, the largest port in Cameroon.

Along the way the ship would collect wood and phosphate that had long been mined by the Gulf of Guinea nations for export to Europe.

When the Hoegh Aronde sank while homeward-bound, 60 nautical miles off Morocco on March 21, 1963, it had 3000 tonnes of sedimentary rock destined to become fertiliser and 2400 tonnes of timber. The 19 crew members were lost.

Fortune shone on Roed – briefly. He didn’t join that trip. He’d found a girlfriend he would soon marry. But he did bring home a souvenir from his travels. Just a small thing. Indeed, microscopic. Unknown to anyone, of course not Roed, not his doctors, or to the family that was to come, he had contracted a then unrecorded disease that today we call HIV.

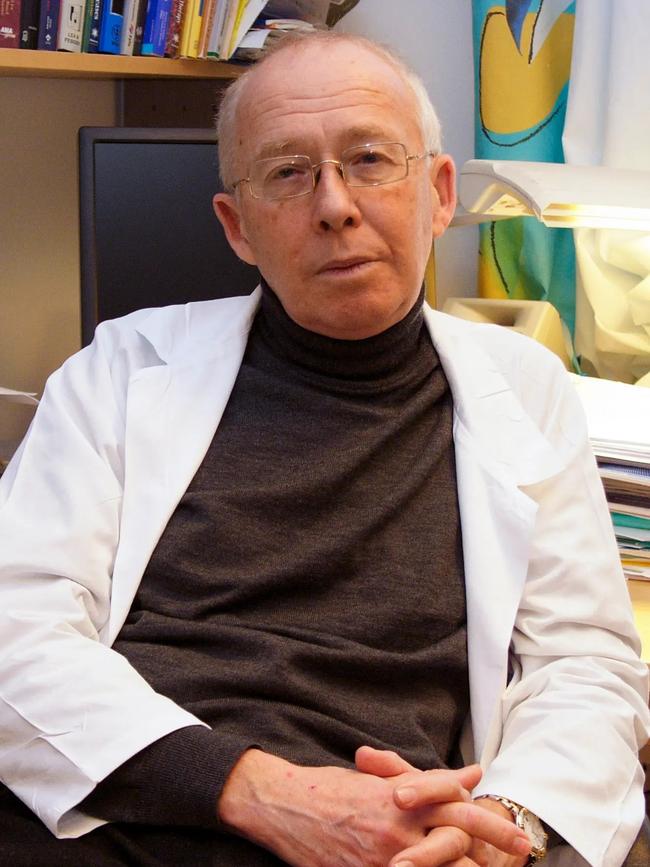

Long after Roed’s death 50 years ago, a young doctor, Stig Froland, who had treated Roed and had kept some body tissues from the always and unaccountably ill former sailor, in 1986 tested them on a hunch for a suddenly newsworthy disease that had emerged initially among the gay men of New York and Los Angeles. Froland made an extraordinary discovery: at some point, Roed had been infected with an unusual variant of the human immunodeficiency virus.

He was the first recorded victim of HIV. Patient zero.

HIV is a virus that, usually, and quite slowly, diminishes your immune system by about 80 per cent; this incapacitated immunity makes a victim vulnerable to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. AIDS can manifest itself as a headache, sore throat, a cough and night sweats. It often showed up as an odd purple skin rash, evidence of Kaposi’s sarcoma, a previously rare cancer that was found mostly among older men from the Middle East and Mediterranean.

With Roed, HIV had arrived in Europe. No one had heard of it in 1962. But two decades on it would change the world. It still does.

Total deaths across the globe from Covid-19 – which effectively shut down the planet for two years from 2020 – have reached seven million. But according to the World Health Organisation, HIV has killed up to 51 million people, and about 40 million are living with it. A total of 630,000 died of it in 2023 while there were another 1.3 million new infections.

But it turns out that HIV is not new. It had been on the back burner since at least the mid-19th century with occasional but unreported outbreaks, commonly centred on Kinshasa, now the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Life was cheap there then and too few cared about the victims of a disease the locals referred to as “Slim” because of the dramatic weight loss it caused.

Roed and his family would become the first cluster to come to the attention of doctors anywhere. But HIV, almost certainly, had slowly and irregularly moved about without anyone realising it. Retrospectively, scientists and doctors now believe there were other outlier cases but the range or symptoms was so varied and complex they did not fit within the diagnosis of any reported and recorded disorder.

A blood sample from a Bantu man taken and stored after he died in 1959 in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, was tested in 1986 and was positive to a variant of HIV. So the virus was already mutating; this was not a new disease.

In 1990, the blood from a Manchester printer, David Carr, was tested and he too had succumbed to AIDS, dying in 1959 from various illnesses after his immune system caved in. Around the time Carr died some Haitians who had worked in the newly independent Congo also died from what doctors assume was AIDS.

Late in 1968, 15-year-old Robert Rayford presented at St Louis City Hospital in Missouri. His puzzling mix of symptoms confounded doctors and after passing through three more hospitals he died in May 1969. Samples retrieved at his autopsy were tested in 1987 and he was confirmed as the first AIDS death in the US. The boy had not travelled overseas, indeed his life was contained to a few mid-western states.

A Danish doctor, Margrethe Rask, who worked in Congo from 1972, fell ill in 1977 with what was later confirmed to have been AIDS. That same year the sole survivor of a Canadian transport plane that crashed in Congo in 1976 was given locally provided units of blood and fell seriously ill, dying in 1980. Subsequently it was confirmed he suffered from AIDS.

HIV probably is the result of the simian immunodeficiency virus found in other primates crossing over in blood-to-blood contact when Africans sought bush food and were bitten or slaughtered the animals. The simian virus has been among other primates for an estimated 32,000 years. The aggressive strain of HIV that emerged in Haiti and spread to both US coasts by 1980, and that would become dominant and spread around the world, disabled its hosts’ immune system relatively quickly – like Rayford’s – and back then sufferers would live about three years.

At first, given that the disease appeared to commonly attack gay men, it was given the acronym GRIDS – gay-related immune deficiency – and briefly was labelled the gay plague. But it had never specifically been a male disease.

In any case, the era of blood transfusions and blood products was in full swing.

The first blood transfusion had been in England in 1665 when physician Richard Lower kept a dog alive with the blood from others. The idea of national collection centres for donated blood coincided with the slow, erratic emergence of HIV.

Poor hygiene at Haitian blood collection centres and the pooling of blood from thousands of donors almost certainly were why it became such a hot spot.

Its association with homosexual men in the early days and its crude labelling led to outbreaks of homophobia, including in Australia and especially in Sydney, perhaps not helped by the so-called Grim Reaper television campaign of 1987. As the shrouded figure with the scythe threw down bowling balls at family groups, an ominous voiceover said AIDS might claim more Australians than World War II.

Ironically, by then gay men largely had changed their behaviour already and it was the heterosexual community’s nonchalant attitude towards HIV that was becoming troublesome. But in 1985, the year the hysteria over HIV peaked – particularly with the treatment of banned Kincumber, NSW kindergarten girl Eve van Grafhorst – trials of antiretroviral treatments that suppressed the spread of HIV were started.

Within a decade combinations of these were proving highly effective in slowing the disease. These have been improved to such a degree that, while there is still no cure, those with HIV can get to a stage where the virus is undetectable, their chances of passing it on are almost negligible and they can even have children without passing it on to them.

It was the progress made in this that led to the rapid development of a Covid vaccine.

Edwina Wright, an infectious diseases physician at Melbourne’s Alfred Hospital and one of Australia’s leading HIV clinicians, says Australians diagnosed with HIV these days live full and mostly normal lives. “If a 25-year-old man came into my clinic with a new HIV diagnosis today (and started treatment) it is very likely he would have the same longevity as a 25-year-old without HIV,” she says. “They have a bright future ahead of them in terms of health and lifespan.” Wright says they may still be vulnerable to some other heath conditions “but overall the news is fantastic”.

The treatments are expensive but very affordable generics are now available on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. These days your life is saved with a daily tablet or two-monthly injection.

It is an enormous challenge, but the UNAIDS organisation released a report in July 2023 – The Path That Ends Aids – that has set 2030 as the date to end the world’s deadliest pandemic, which is now a financial and political, not medical, challenge. Almost 30,000 Australians are living with HIV and across the world 30 million infected with it are on retrovirals.

None of this was of any value to the Roed family whose puzzling illnesses mystified Froland and his colleagues. Arne’s daughter Bente, who was born with HIV, died on January 4, 1976. Arne died on April 24 that year and his wife, Solveig, followed on December 21.

Froland later concentrated on studying infectious diseases and served as a professor at the University of Oslo until his retirement. In 2022 he published a book, Duel Without End: Mankind’s Battle with Microbes, that traced our never-ending fight against viruses. In 2012 he was awarded the Order of St Olav, Norway’s highest civilian honour.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout