Out of house and hope

Homelessness is at the core of the toughest issues facing the west’s indigenous population.

In a quiet street in suburban Perth, Jenny has been a public tenant in her two-bedroom unit for nine years.

Two years ago, she managed to get back from child protection her youngest son, now 11, but keeping him is dependent on having a roof over her head.

At 39, she faces a range of challenges typical of many Aboriginal public housing tenants.

She holds down part-time jobs as an interpreter for West Australian government departments, but is hampered by diagnoses of schizophrenia and diabetes.

Last month, she received a letter of termination for dirty walls, floors and cockroach residue in her rented property.

If she’s evicted, she will become another statistic in a rate of Aboriginal homelessness in WA that is 13 times higher than for non-Aboriginal people.

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, they make up almost one-third of the state’s homeless population despite being only 3 per cent of the population.

If her child is removed into care, Jenny’s son will also become a statistic in WA’s record level of Aboriginal children in care.

In the state that removed thousands of children during the worst days of the Stolen Generations policy, the figures show that an Aboriginal child is still 10 times more likely than non-Aboriginal children to be placed in state care.

Children are removed from drug-addicted or neglectful parents, but they may also be removed because the parent has nowhere to live.

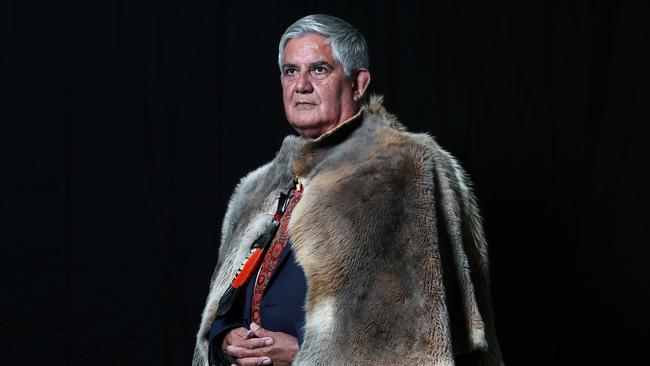

Wyatt’s hometown

Federal Indigenous Affairs Minister Ken Wyatt told an Aboriginal housing forum in Perth last November that “housing policy is a key element of closing the health and longevity gap we have in society”.

But if he is to improve the revised Closing the Gap targets being set by the Morrison government, he will need to look to the suburbs of his own city, Perth, for improvement.

The problem was well understood by the state Labor government, which came to power two years ago. If one part of government was evicting children and another part removing them into expensive state care, the system was failing.

Premier Mark McGowan’s government announced a remedy — a “joined up” model of welfare bringing together housing, disability services, family support, and child protection under a single Department of Communities.

Under the department’s “joined up” approach, a person with a chronic disability facing eviction would come to the attention of departmental housing and welfare branches.

If a child faced eviction with its parent, housing would talk to social services; if that child was a ward of the state, child protection would be involved.

Termination ‘last resort’

Yet two years on, Jenny and her son Ryan (not their real names) learned of the threat of eviction in the historic week that Wyatt — who has spoken often and forcefully about the failure of government departments to talk to each other — became the nation’s first Minister for Indigenous Australians who was indigenous himself.

Jenny’s was not the only case. The Australian was told by crisis housing agencies of other cases that week, although the families cannot be identified because they include children “flagged” by child protection.

Ms M, who has rheumatic heart fever and epilepsy, was served an eviction notice that would leave her adult daughter and seven-year-old granddaughter without a home. Her rent was up-to-date but she was served a termination notice for overcrowding.

Ms Q has survived chronic domestic abuse but faces eviction due to rent arrears, along with five children, one a 12-month-old with a heart condition. After The Australian made inquiries about her case, she was put on compulsory income management and the eviction has been delayed.

When these cases were put to the Department of Communities for a response, The Australian was told that terminating a tenancy was “a measure of last resort”.

“Children’s welfare, wellbeing and safety are paramount and thoroughly considered prior to any eviction action progressing,” says departmental assistant director-general Jackie Tang.

Tang says families are offered help with tenancy issues such as property standards, disruptive behaviour and rent arrears.

Yet the state government has just been forced to abandon a $35 million Support and Tenant Education Program, or STEP; it will be replaced by a new tenant support program in October.

New program

Tang says STEP’s failings were that it “was largely reactive, without a targeted focus on earlier intervention and prevention”.

She says a new program, called THRIVE, will “have stronger focus on early intervention, supporting people to identify and tackle problems before they become too great or reach crisis”.

She cited the state Auditor-General’s report last year on “managing disruptive behaviour in public housing”, which said the department “generally manages these disruptive tenancies well”.

In fact, Auditor-General Caroline Spencer’s comments were considerably less positive. She criticised the department’s dual “and sometimes opposing” roles as landlord and supporter of tenants. Then there was WA’s policy of “three strikes”, which sees a tenant issued with a termination order if three complaints are upheld.

“We found strikes were issued against tenants with complex mental health illness, family violence or intergenerational dysfunction,” she wrote.

“The department does not direct resources towards early intervention for these tenants.”

Only rhetoric changes

This month, seven not-for-profit welfare agencies in mental health, domestic violence, tenancy and youth support in Perth called for a moratorium on evictions, which they say exceed more than one a day and disproportionately affect the state’s poorest families.

More than 300 tenants were served with court orders or evicted by bailiffs in the 10 months to April, with another 200 issued with termination notices to leave their public housing property.

“We’ve seen children who were evicted with the grandparents they lived with, and are living in tents in the backyard of family houses or moving from house to house as they wear out their welcome,” says Tenancy WA director Kate Davis. “They cause overcrowding wherever they go and the children have years of disruption from schooling.

“Over the years, we’ve seen an improvement in the rhetoric. Five years ago, housing would say: ‘We are the landlord of last resort and our role is to manage public housing as an asset.’

“They were clearly of the view that they were not a social service agency. They now say things like: ‘We understand housing is an important part of people’s wellbeing.’ But it’s only the rhetoric that has changed.”

Davis said Tenancy WA recently acted for a mother with a primary school-aged child flagged as vulnerable by child protection officers.

“The housing authority tried to evict the woman and there appeared to have been no communication between the two departments. When we raised with child protection workers that all the plans for the child’s safety would be undone if she was made homeless, they agreed.”

Successful project

The scale of the crisis has led to the First Nations Homelessness Project, which helps Aboriginal families facing eviction to clean up houses and pass inspections.

It has been a spectacular success; over two years, it has helped 180 housing tenants with 531 children in their care. Only six of those tenancies ended in eviction.

Project founder Jennifer Kaeshagen says the government’s STEP “support” program failed Aboriginal tenants such as Jenny and Ryan, who were helped last week by First Nations to clean up their house in the hope of avoiding eviction.

“STEP would come out and stand on the doorstep and read the eviction letter to the tenant, but they didn’t offer practical help,” says Kaeshagen.

“Yet almost every threatened tenancy is about property standards, not disruptive behaviour.

“Child protection and housing officers regularly refer their clients to us, even though we get not a single dollar of state funding.”

Instead, funding arrived after previous federal indigenous affairs minister Nigel Scullion and two staff members volunteered at one of its house clean-ups during a visit to Perth.

Scullion’s successor, Wyatt, has told The Australian he will extend federal Indigenous Advancement Strategy funds to the project when its current funding runs out in October.

Generations of trauma

The clean-up team now employs former tenants who were themselves saved from eviction. Team leader Mona Yarran, 45, says two generations of her own family were removed as children due to lack of suitable housing.

“It’s been happening for generations — me and my brothers were taken from our mother because she couldn’t deal with the trauma in her life.

“So I know what I’m dealing with when I meet these clients.”

Tenancy WA’s Davis says most of the juvenile offenders in Perth’s Banksia Detention Centre — 85 per cent of whom are Aboriginal — have been homeless during their childhood. “My guess is that it would be all of them,” she adds.

The link is seen on a daily basis in the Children’s Court of WA, says a senior justice worker who doesn’t want to be identified.

“The point about homelessness is: once the kids are taken, social security payments are reduced.

“Then mum can’t afford the rent so she’s evicted and has to get in the queue for housing, public or private.

“And it’s impossible to get your children back without housing.”

Stolen legacy

The invisible factor behind many failing tenancies is the legacy of historic child-removal policies, says tenants’ advocate Betsy Buchanan, who works with hundreds of clients seeking help from Catholic welfare agency Daydawn.

“Aboriginal people in this state were subjected to historic removals and institutionalisation at a far higher rate than every other Australian jurisdiction,” she says.

Many Stolen Generations clients have trauma-related illness or addiction, she says, and more than 40 per cent have been homeless at some time.

Many clients have qualified for payouts resulting from the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse.

But more urgent is a roof over their head. “I don’t think the money people are waiting for is as relevant to people without a home,’’ Buchanan says.

“ Housing matters more. If we are sincere about making sure that history never happens again, we must change housing policy.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout