Ours to command: lessons republicans must learn

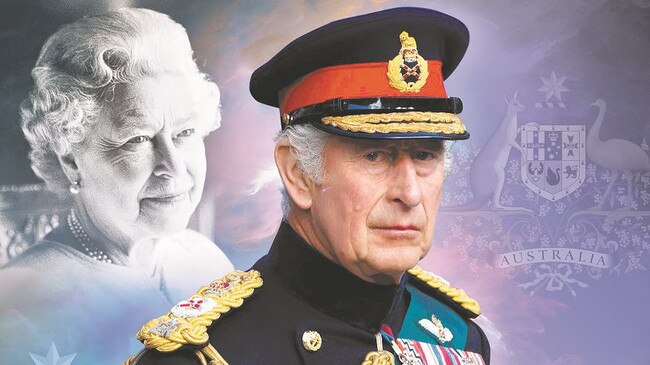

King Charles is far better prepared to manage this issue than his Australian advisers and a public lacking the energy or game plan.

Anthony Albanese has done the republic a service by dismissing any referendum this term. The notion is absurd. The republican movement in Australia lacks enthusiasm, traction and strategic direction. It seems outdated in a world where progressive politics and young people are consumed by climate change, individual feelings and identity, justice for women, racial and gender issues.

The stirring battle cry a generation ago – an Australian as head of state – now seems devoid of mass mobilisation.

It is an idea from an earlier age that fell from fashion and doesn’t slot into minority grievances and the self-absorbed cultural transformations now shaping progressive priorities.

The Prime Minister said before the election that his referendum priority was the Indigenous voice to parliament – this reflects Labor sentiment and constitutes a daunting challenge in its own right. If the voice fails at the referendum, don’t expect any republican referendum for many years.

For some time, prominent lions of the republic – think Malcolm Turnbull – said the republic should be put on ice during the life of Queen Elizabeth II. This had a certain logic but was a sign of weakness. It conceded the grace and standing of the Queen was an insuperable obstacle. It assumed that the constitutional monarchy would be much weakened under King Charles.

Obviously, Charles cannot match his mother’s standing. But his early speeches reveal a new King invoking Elizabeth’s ethic of service, dedication, impartiality and constitutional propriety.

Don’t overlook the possibility of ongoing support for the new King and for the institution of constitutional monarchy. And don’t overlook that such sentiment is reinforced by other events – the discrediting of the US presidential model by the reckless sabotage of Donald Trump, sure to be a negative legacy for our proposed presidential transition.

The reality is that the republican issue will be decided in Australia, not Britain, though the image and popularity of King Charles must be a factor.

During the Queen’s death and the elevation of Charles as King – and Australia’s new head of state – Albanese has enhanced his standing, shunning politics and acting as the authentic national leader.

The republic debate in Australia is always about two issues – Buckingham Palace and Westminster democracy – as shown by the 1999 referendum.

That model sought to terminate our constitutional ties with the palace but retain the Westminster system by having a “safe” non-partisan president not elected by the people and without any popular mandate.

But the referendum was defeated by a dual alliance: support for the Crown, and a populist sentiment demanding a different model – a directly elected president enjoying a stronger, direct mandate than the prime minister, a position neither John Howard nor Paul Keating would countenance. Creating an institutional rivalry between the prime minister and president in a new republic would be disastrous for this country. These complex obstacles to the republic will reappear in any referendum. The public might prefer a directly elected president but any such model will face fierce opposition from monarchists and many republicans who, post-Trump, believe in the Westminster system now more than ever.

King Charles knows how to handle any future republican debate. That’s because he has done it before. In 1994, Charles visited Australia to deliver a powerful message as the republican campaign gathered strength. Following advice to the Queen on the republic from then prime minister Keating in 1993, the palace sent Charles to Australia with a carefully prepared message.

It culminated in his Australia Day address when Charles said the decision resided with the Australian people. “This is something which only you – the Australian people – can decide,” he said. He made clear the monarchy made no claims on this country. He went further, saying it was not surprising that some Australians wanted a change in their institutions – adding “and perhaps they are right”.

This was a different definition of duty – actually welcoming the republican debate. This is how Charles will respond as King when the issue reappears.

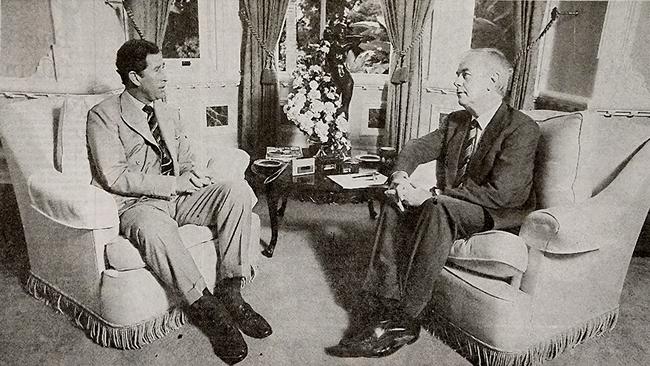

In an interview I conducted with the then prince of Wales during his 1994 Australian tour, he was even more forthcoming.

Indeed, Charles welcomed the republican debate as a sign of Australia’s maturity and “as a perfectly sensible thing to be doing in the light of changing circumstances”. He said if Australians decided on change “there’s no point panicking about that or thinking it’s some frightful insult or something to the Crown”.

He was philosophical: “Who knows what’ll happen in 30 years’ time. I don’t know.”

Criticising media reports that the royal family was striving to hang on to this country, Charles was outspoken: “The point that I would like to get across is that we don’t own this country, we’re not making money out of it or anything like that. We are merely doing what we consider to be, as a family, our duty here by the Australians. All anybody has tried to do is to help, encourage and assist,” he added.

“The other thing I find extraordinary is the way in which the media in particular are always talking about an involvement in this country from the monarchy’s point of view, as if somehow we owned the place, and that to be denied the chance to be sovereign of Australia is something terrifyingly awful.

“I think within a democratic system, it’s not a bad thing at all to be able to discuss it without everybody beating each other over the head and shouting. Clearly, there’s always two ways of looking at things … you’d be jolly lucky if you had a system that everybody appreciated,” the then prince said.

“There are advantages and disadvantages to a republic, as much as there are in having a monarchy. In the end, there’s got to be a debate, I suspect, to help reveal – and perhaps this will help to reveal – some of the hidden advantages and strengths of the current way of doing things.”

Asked how he would respond if Australians decided on the republic, Charles sounded almost enthusiastic about an Australian republic – this, of course, could not be his response as king.

Speaking in 1994, he said: “I have the greatest possible affection for Australia and it’s not going to make the slightest difference. You’d come as a visitor from a country with which Australia has very close relationships, you would come very much as a Commonwealth visitor. And I’d be able to go and visit the people I haven’t been able to see … and find out a damn sight more about Australia because I’d be able to do it in a private way.”

Just as during the 1999 referendum the monarchists had no supporting statement from the Queen, in any future referendum they will have no supporting statement from King Charles. Indeed, he is likely to depict any referendum process as a sign of Australian maturity.

And that word maturity is the key to the entire debate.

There is an institutional problem with Australia’s head of state being determined by a monarchy in another country. Australians have no say, no control and no influence over the appointment of their head of state. Ultimately, this will be untenable and must change. But when does that point arrive? How long might the British monarchy exist? How might the Queen’s death reshape sentiment over the next generation?

A republican Australia is the inescapable logic of our independence, but how long that journey takes defies prediction. It might need to see the title “president” banished and the title of “governor-general” retained as our head of state after ties are severed with the British monarchy. That would suggest change with continuity, ultimately the best prospect.

The current republican movement is embarrassingly unfit for the job. It seems to have learnt nothing from the defeat nearly 25 years ago. The fact that some prominent republicans were beating the drum even before the Queen’s funeral points to a nauseating and clueless ineptitude. They seem not to know their own country – let alone how to spearhead its new constitutional order.

The lesson from Keating in the 1990s and from Albanese’s behaviour now is that the republican issue is not primarily about the Queen or King. It is about Australia – our future, and our aspirations. It is about how we see ourselves and, above all, whether we possess the collective skill to agree on a republican model.

When Keating advised the Queen in 1993 it was time for the republic, they reached an agreement – the royal family would be left out of the coming political battle. When the Queen died, one of the most moving Australian tributes came from Keating, the arch-republican. This is because there was no contradiction. You can respect the Queen or King but still champion the republic.

The republic will never win when presented as a repudiation of Australian history. Howard always understood this point. It is the fatal trap for republicans, yet many recently embraced this folly with their noisy and false assertions that the Queen was a moving force in authorising or encouraging Gough Whitlam’s dismissal in 1975. We were expected to believe that 70 years of impeccable constitutional propriety across all Commonwealth countries where she was head of state was interrupted by a senseless and malevolent lurch by the Queen to destroy Gough. It was a case study in immaturity.

A more serious defect was the constitutional model endorsed early this year by the Australian Republic Movement. A weird hybrid, it proposed that all parliaments – state, territory and national – could nominate presidential candidates, with up to 11 nominees then being put to a direct popular vote based on preferential voting.

Under this model, a president could be elected with about 20 per cent of the vote. An election contest would guarantee political campaigns, the media would support or attack according to its preferences, states would work to get up their nominee as president, and any chance of an impartial head of state above the fray would be lost.

Keating branded the model a “massive shift” in our system of government. So did Tony Abbott. The model recalled Howard’s 1999 warning that direct election was the worst of all worlds, and that even the best effort to limit the president’s powers would not prevent rival popular mandates between the prime minister and president guaranteed to compromise our Westminster system.

When he championed the voice to parliament, Albanese said Australia was not a “whole nation” until this repair was done. He offered the nation a vision. It cannot guarantee success, but it is a vision. Likewise, when Abbott as prime minister talked of Indigenous recognition, he said the purpose was to “complete” our Constitution.

The only hope for the republican movement lies in its reinvention, top to bottom. It has no vision and no strategy capable of mobilising a broad-based coalition. If it thinks King Charles can substitute for its own failures, then the republic will remain a dream for a distant time.

King Charles, deeply familiar with our long but dismal debate about the republic, is far better prepared to manage this issue than his Australian advisers who sit atop an Australian public lacking the energy or game plan to pursue the republic.