One small step of a remarkable man

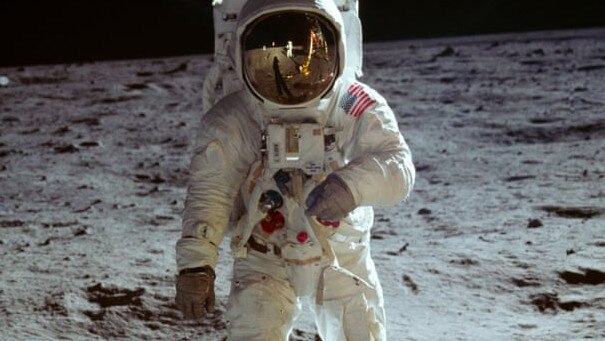

The first man chosen to step onto the moon was quiet, modest and calm under pressure.

The first man chosen to step on to the moon was one of the quietest, most modest, and calmest under pressure. Neil Armstrong was much more than an astronaut. He was one of the greatest aviators, with an advanced understanding of engineering.

As he prepared to set foot on the moon on July 20, 1969 — 50 years ago this month — Armstrong brought his experience from flying 78 sorties as a naval fighter pilot in Korea and as a test pilot at Edwards Air Force Base flying the X-15 rocket plane among others. He signed on to the US Air Force Man in Space program before transferring to NASA.

His highest praise came from other pilots. When Armstrong and NASA pilot Dave Scott orbited on Gemini 8 together in 1966, and their spacecraft began spinning out of control, pinning them to their flight seats with massive G-force, Armstrong coolly stabilised it for re-entry.

Scott said later: “The guy was brilliant. He knew the system so well. He found the solution, he activated the solution, under extreme circumstances … it was my lucky day to be flying with him.”

A man on the moon

Armstrong’s encyclopedic knowledge of engineering and computer systems was critical as he and Buzz Aldrin undocked from the Apollo 11 command module circling the moon, leaving pilot Mike Collins alone up in orbit. They began their descent to the surface in the lunar excursion module.

The undocking from the command module gave the LEM more speed than planned, as the onboard flight computer guided them down from orbit, setting them up for disaster.

Descending towards the planned landing area, Armstrong could see they were going to overshoot on to a boulder field, with rocks as large as a bus.

He calmly took over from the computer and manually controlled the landing rocket with commands over an electric network called fly-by-wire — which Armstrong himself had helped develop a decade earlier.

With only one chance at safely touching down, he piloted the craft beyond the boulder field towards a clearer site but burned more fuel than planned.

NASA estimated they had less than 30 seconds of fuel left when they touched down.

Years later, when asked about the fuel level, Armstrong answered: “Well, when the gauge says empty, we all know there’s a gallon or two left in the tank.”

The first words

In 2006, I was doing voice editing for the next generation of our neural-controlled communication system, called NeuroSwitch, at our US office next to Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Fairborn, Ohio, Neil’s home state.

After more than a decade of covering shuttle launches at Kennedy Space Centre for US TV networks, I thought for fun I’d analyse man’s first words walking on the moon. All over Earth, people heard Armstrong say: “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” But from the day he returned to Earth Armstrong insisted he had said: “That’s one small step for a man …”

I ran a NASA recording of Armstrong through a Canadian GoldWave audio editing program I’d bought online and found an amplitude variation — a sound wave — that I believed coincided with the place where he would have said the “a” in “That’s one small step for a man …”

As a Queenslander from the flat western plains, where vowels are frequently purely elective, it seemed to me that Armstrong, from Wapakoneta, on the western plains of Ohio, might have a similar casual attitude towards, say, the indefinite article “a”.

I called an old friend at NASA, Hugh Harris, who connected me with Auburn University’s James Hansen, Armstrong’s authorised biographer and the author of First Man, which was made into the movie starring Ryan Gosling.

Hansen forwarded my analysis to Armstrong and three days later I received an email from the astronaut.

He suggested we meet at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC. We were shown into a small office at the museum. There were five of us — Armstrong, Hansen, a NASA rep, me and my colleague, biomechanical engineer Rano Singh, who did a comparison of the two phrases in that famous first sentence, between “For (a) man …” and “… for mankind”.

I played the edited analysis and walked the group through the graphics of the sound file. Armstrong studied them for some time.

News of the meeting went around the world in the months that followed. Audiology and linguistics academics blogged a small firestorm of angry criticism, condemning the use of an off-the-web audio editor and denouncing the suggestion that anyone but an earnest academic like them would give it a shot.

After going over my presentation, Armstrong pronounced it as “persuasive”, affirming what he always believed about himself. He discussed the acoustics of his space suit and helmet, which had two microphones with typical NASA redundancy, the vagaries of transmission across space to the Parkes dish in Australia, and how he came to say what he did when he stepped down.

Then I asked him who wrote that historic sentence. He smiled and said quietly: “I did.” I asked him when, and he said: “After we landed.”

Unplanned walk

When Apollo 11’s lunar module touched down on the moon, Armstrong recalled that Mission Control first wanted them to launch right back up again, without a moonwalk. Their reasoning was they’d just beaten the Soviets to the moon, the crew was alive, so head back while they were ahead. America had won the space race.

Armstrong and Aldrin argued they had come too far not to get out, step on to the surface and place an array of instruments to collect data for NASA.

They waited six hours and 38 minutes for Mission Control to make a decision.

That, said Armstrong, was when he wrote his first sentence for the step down.

“How did you come up with it?” I asked.

He explained with the concise precision of a test pilot and engineer, that it seemed logical that he was making that small final step off the ladder, but that the implications affected all of us, all mankind. He shrugged off rumours that NASA had drafted it, or that his brother had suggested it, or that it came from anywhere except that small solitary spaceship sitting silently on the surface.

He had given a similar account to Hansen for First Man, recalling: “I didn’t think it was particularly important, but other people obviously did. Even so, I have never thought that I picked a particularly enlightening statement. It was a very simple statement.”

As for the so-called missing “a”, he told Hansen: “For people who have listened to me for hours on the radio communication tapes, they know I left a lot of syllables out. I think that reasonable people will realise that I didn’t intentionally make an inane statement, and that certainly the ‘a’ was intended, because that’s the only way the statement makes any sense. So I would hope that history would grant me leeway … even if it wasn’t said — although it actually might have been.”

When Mission Control cleared Armstrong to leave the module, he eased himself out on to the top of the ladder.

The fuzzy black-and-white video, streaming live from the lander module to the CSIRO dish at Parkes to Houston, showed Armstrong lowering himself down the rungs, pausing, then easing his boot on to the lunar surface.

Armstrong in Australia

Armstrong came to Sydney in August 2011 on a lecture tour with the Certified Public Accountants of Australia. His father was an auditor. During his stay I introduced him to Qantas captain Richard de Crespigny who, with his flight crew, saved 469 people on board QF32 when one of its jet engines exploded, critically damaging the aircraft’s control systems, after takeoff from Singapore in November 2010.

I emailed an introduction to Armstrong, and he emailed back saying he’d read accounts of QF32 and was looking forward to meeting de Crespigny. The two pilots connected by email and hit it off right away.

When Armstrong arrived in Sydney, de Crespigny and his good friend Simon Ford hired the beautifully restored wooden-hulled steam launch Lady Hopetoun for a day cruise on Sydney Harbour. Armstrong loved it. He talked steam power with the crew and discussed flying with de Crespigny’s father, who also was an octogenarian pilot.

That night, de Crespigny, his dad and Armstrong booked time in a Qantas A380 simulator. Like most military and commercial aircraft in the world, the A380 is controlled by fly-by-wire.

It was that encyclopedic knowledge of the A380’s systems that helped de Crespigny, as captain of Qantas flight QF32, when one of its Rolls-Royce Trent 900 jet engines exploded on takeoff from Singapore.

The explosion caused catastrophic system failures through the aircraft before the pilot and his colleagues on the flight deck could bring it to a safe landing back at Changi airport.

“I wanted to make contact with Neil,” he said, “because I knew he’d be interested to see how the fly-by-wire he helped create had morphed into the technologies that everyone in the world who flies now takes for granted.”

Flying with a legend

De Crespigny’s dad, Peter, had flown all his life, and was an accomplished pilot, still flying at 85. But on the Lady Hopetoun, he told his son: “When we go in the simulator, I can’t sit next to Neil because I’m a simple pilot and don’t deserve to sit next to Neil Armstrong.”

Richard de Crespigny told Armstrong, who went to the father and said: “You know, Peter, why don’t we old guys get together to show this young guy Rich what we can do?”

De Crespigny invited Armstrong to take the left-hand pilot’s seat in simulator, the captain’s seat. As Armstrong settled in and snapped on his fight harness, de Crespigny explained the A380’s velocity rotation capability. Armstrong got it straight away.

As the simulator gently rocked, replicating the feelings on takeoff, de Crespigny recalls “a feeling of intense pride to be sitting next to the man who in aerospace had accomplished more than anyone else on the planet”.

When flying with another pilot who has the controls, aviators remain alert to all the nuances of the aircraft as it takes off, until they’ve judged if they can trust their colleague. Many use the phrase “He/she has safe hands” to describe a completely reliable aviator.

“It was obvious that this pilot, at 81 years of age, was still completely comfortable and confident flying the A380, the world’s most advanced aircraft,” de Crespigny says of Armstrong.

Once the simulator replicated reaching cruising altitude, 6000 feet, Armstrong levelled the aircraft off and de Crespigny began discussing the fly-by-wire technology, aware that he was talking to one of the test pilots who first developed it.

When they “landed” the simulator, de Crespigny got out of the right-hand seat and his father climbed in. Richard heard the astronaut say over the intercom: “Now, let’s show what we can do, Pete.”

De Crespigny, who watched his dad co-piloting with Armstrong, said: “I saw my father who still pilots his own plane sitting next to this legendary astronaut, and felt amazingly emotional.”

After the two veteran pilots “landed” for the last time, Armstrong leaned over to shake his co-pilot’s hand, and said: “Nice job, Pete.” It was classically concise, and memorably the highest praise imaginable from one aviator to another.

Final flight

When Armstrong returned to the US, we corresponded by email until a few days after his heart surgery in August 2012.

In his last email to my wife and me, he wrote: “I am creeping back to life. I will get back to you soon. Neil.”

Then he was gone. He was 82.

The next day, when Richard de Crespigny heard the news, he was flying an A380 as QF2 from Singapore to Sydney. Both decks of passenger seats on the great jet were filled, and before they rolled out for takeoff, he made the following announcement over the public address system: “Ladies and gentlemen, on behalf of everyone in the world’s aerospace industry, we are dedicating this flight to Neil Armstrong. He represented all that is great in aerospace. He died yesterday at 82.

“Most will know him as having the right stuff as the first person who walked on the moon, as a navy pilot, a test pilot, astronaut and university lecturer.

“Most may not be aware of the great contributions he made to aerodynamics, hypersonic flight, something pilots call supercritical wing, and fly-by-wire.

“I knew him as a modest, warm friend and mentor, with an acute mind through to his last day.

“On this flight, we will be cruising at 40,000 feet, three-quarters of the way into space.

“This was Neil’s playground, where he felt completely at home.

“He loved flight, and the A380, and Qantas. Last year, we took him in the A380 simulator in Sydney. When we reach cruising altitude, I hope you can look to your neighbour and make a toast to Neil: one of the greatest aviators of all time.

“We will all miss Neil Armstrong. He achieved so much more than walking on the moon. He showed us how a man from humble beginnings can, through many small steps, rise and forge giant leaps for humanity. He leaves behind a legacy for the good of every person on planet Earth. May he rest in peace.”

Armstrong remembered

NASA arranged for us to be at his memorial service on September 13, 2012, at the National Cathedral in Washington, DC. Richard de Crespigny flew in from Sydney with his wife, Coral, and we travelled to the service with my Washington mentor, Paul Mahon.

At the centre of one of the great gothic cathedral’s gorgeously coloured stained-glass windows is a moon rock brought back by the three Apollo 11 astronauts. It is called the Space Window and was designed by St Louis artist Rodney Winfield.

NASA administrator Charles Bolden spoke of Armstrong as the best possible person to be the first man to step on to the moon.

Former Apollo astronaut Gene Cernan said in his eulogy: “No one, no one, but no one could have accepted the responsibility of his remarkable accomplishment with more dignity and more grace than Neil Armstrong. He embodied all that is good and all that is great about America.”

At the landing site of Apollo 11’s LEM, there is a plaque left on the moon by Armstrong and Aldrin and signed by them, Collins and US president Richard Nixon.

It declares: “Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the moon July 1969, A.D. We came in peace for all mankind.”

It was a remarkable statement, by the first nation to send representatives of our species across that first gulf of space. It showed the true greatness, vision and adventure and admirable modesty of the US at arguably its finest hour.

For a brief moment, when Armstrong’s first boot prints were impressed into the grey dust of the moon, the people of Earth appeared to feel united, borderless, as a single race.

As Hansen alluded in his biography, Armstrong was the best in all ways to be the first man.

He is a superlative example to the next man or woman who follows in his boot steps.

Peter Shann Ford covered the US space shuttle program for more than a decade as a news anchor with CNN and NBC, before founding Control Bionics, a neuroelectrics control and communications company.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout