One secret, two families: uncovering hidden ties between Kath Walker and Brisbane’s Cilento family

This is the story of two Australian families – one Indigenous, one white – bound by the birth of a child, in circumstances that demanded the utmost secrecy.

It is a story of prestige and of poverty; of Aboriginal politics and literature; and, it seems, love.

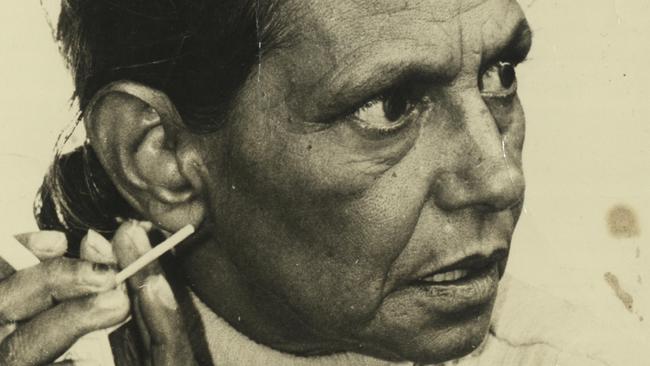

It involves two well-known Brisbane names: the Cilentos, Sir Raphael and Lady Phyllis, who were among the worldliest and most important families in the state in the 1950s; and Kath Walker, an Aboriginal woman who went to work for them in 1951 as a domestic. During her time in their fine home she would become pregnant to their son, Raff, and it seems that she never had a conversation with her employers about it.

In a surreal twist, she would leave the house to become more famous than any of them, as poet Oodgeroo Noonuccal. Her verse, much of which we now recognise as a cry for respect, and reconciliation – is still read in schools.

The story is being told in full, for the first time, in a new book, This Accidental Present, by Queensland filmmaker Ross Wilson.

“It took time to piece it together,” he says, “and I wanted to get permission from both sides of the family to tell it. And now I do.”

head

“Domestic Help Wanted”: so ran the ad in Brisbane’s The Telegraph in May 1951.

Sir Raphael Cilento and his wife, Lady Phyllis Cilento, had busy lives. He was an expert in tropical medicine who had been tasked with the eradication of malaria and leprosy in Queensland. He also was a barrister who had served as UN director for refugees and displaced persons after World War II; he had been one of the first civilians to enter the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in 1945; and he was an outspoken conservative and advocate of the White Australia policy.

His wife, Lady Cilento, had been the only female student in medical school in Adelaide in 1919. She would become a specialist in pediatrics; an advocate for maternal and child health; a proponent of a new regulation, allowing fathers to be present in birthing suites; and a broadcaster and writer.

They lived with their six children in a house they called Seiano, with a flagpole out the front, from which they flew the Cilento family crest.

Walker’s family story could not have been more different. She was raised left-handed and barefoot near Moreton Bay, fetching yabbies, oysters and crabs at low tide and exploring the rubbish dump. She used to make slingshots to hunt for lorikeets (“greenies”) that she would take home, cook and eat. She left school at age 13 after her parents arranged work for her as a domestic. She had bounced around a few different employers, often living in a boxed-off room under the stairs.

In her early 20s she married a welder and part-time boxer, Bruce Walker, with whom she had a son. For a time she took in washing to make ends meet. Then she saw the ad for a housekeeper.

Lady Cilento greeted her at the door. “She was a public figure in the media with her columns about bringing up children, and he was well known … this was a very prominent and prestigious family,” Wilson says.

Kath Walker got the job and worked for the Cilentos for five years, occasionally living in one of the flats below the main house. Their son, Raff, wasn’t living there – he had a wife and three children – but he was a frequent visitor.

“When she became pregnant, it seems that she allowed everyone to think that her husband was the father,” Wilson says. “But there is plenty of evidence that Raff knew he was actually the father. For one thing, he told a Bulletin journalist (in the 1990s) that Kath was the love of his life, his intellectual match and soulmate.

“But they both knew the pregnancy would create a scandal and in all probability lead to divorce for Raff. The courts might not allow him to see his children again. He couldn’t predict how his parents would react. Kath could also be sued for divorce and lose custody of one or even both of her children. She couldn’t know how Lady Cilento would react to a scandal involving her son.

“The only viable alternative to truth was secrecy.”

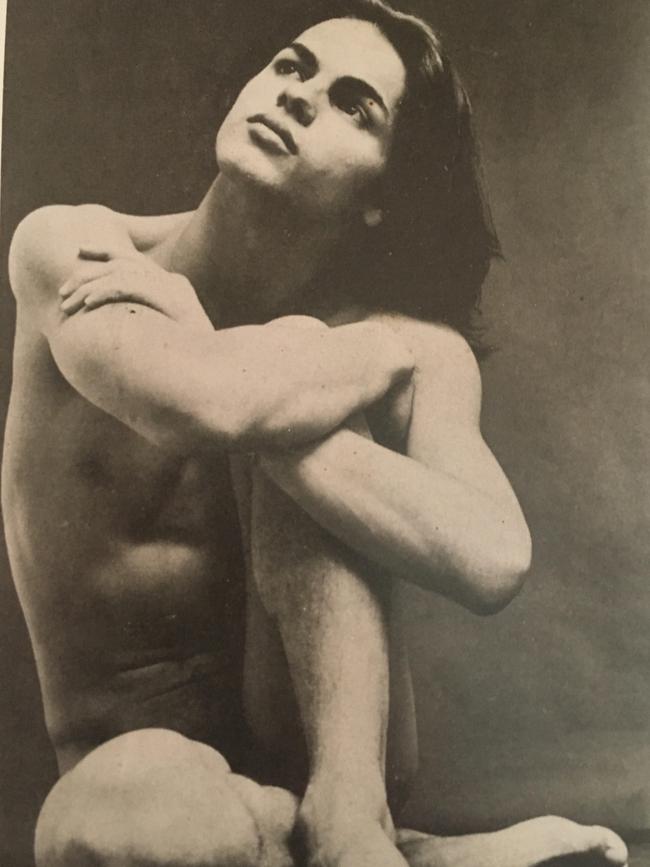

Walker gave birth to the child, a boy, in February 1953. According to the birth certificate, Raff was the “medical attendant” (he was a trained doctor) in the birthing suite. She called her son Vivian, with the middle name Charles, which was Raff’s middle name. She put her husband’s name down as the father, but as Vivian grew he began to look more like a Cilento.

“Well, they were a knockout good-looking family and Vivian was extremely good-looking as a young man,” Wilson says.

“One of Raff’s sisters, Diane Cilento, who married Sean Connery, she was the same, very good-looking. There is certainly a resemblance in terms of how attractive they all were.

“But there was no way to acknowledge the relationship. I don’t think Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people got married very much in those days, and Raff was married, and she was married.

“It was a highly inflammatory situation which could have led to … well, in those days, they used to publish the divorces in intimate detail. You had to go to court to get a divorce and all the details were brought up, and it was a big scandal.”

Wilson notes that the Cilentos helped Walker financially, shortly after Vivian was born, by paying off her mortgage for her.

In time she moved on from their employment, becoming prominent in Queensland social justice movements. She also joined a writers group, where her talent began to blossom.

“She was a great and voracious reader all her life. When she was working as a housemaid at other people’s houses, she would read through the library,” Wilson says.

“So, she had that natural inclination to read and write. There were, at that time in Brisbane, small groups of political writers who were trying to create a movement for social change, especially for Aboriginal people, and she was encouraged by that.”

Walker was catapulted into the wider Australian consciousness on publication of her first collection, We are Going (Jacaranda Press) in 1964, in which she wrote about what we now understand as respect and reconciliation.

The book sold 10,000 copies – unheard of for Australian verse – but she was circumspect, saying: “I am well aware that the success of We are Going was not due to any greatness in my simple voice but to the fact that it was the work of an Aboriginal … I had what I believe the French called a succes de curiosite.”

She was soon invited to address conferences, literary salons and schools. She became more confident, adding directness to a lightness of touch and humour in what would become the campaign for the 1967 referendum.

When Robert Menzies offered her a drink after a parliamentary meeting, she gently reminded him that in Queensland he could be arrested for supplying alcohol to an Aboriginal person.

Her young son, Vivian, often accompanied her on the road, but it seems that he saw his father only twice in his life.

On the first occasion, Raff, who by then was living in New York where he worked as a brain surgeon, summoned him to Brisbane airport.

“Vivian, by then a teenager, caught a cab to the airport at Eagle Farm … it was a hangar in those days, with a cocktail lounge,” Wilson says.

“He was a worldly kid. He’d been mingling all his life with politicians, radicals, thinkers, artists, religious leaders. He wasn’t daunted. He’d attended political rallies, art gallery openings, poetry readings.”

They did not hit it off, however, with Vivian later saying the meeting felt like “an interview with this man who was my father but could have been anyone”.

In 1970 Vivian won the first Aboriginal scholarship to attend the National Institute of Dramatic Art. He strode the stage in London before moving to Hollywood, where he became part-owner of one of the famous gay strip clubs. He was glorious to look at and cashed up from tips. Friends report seeing Michael Jackson deep in conversation with him one night. (To find out more, you’ll have to get the book.)

But it was a dangerous time, says Wilson. By the mid-1980s, “some gay men were dying from what seemed like a mysterious flu … as Vivian strolled around his apartment nude, his lover noticed small skin spots behind his knee and under his arm … AIDS was not yet officially named.”

A short time later, Vivian received a second message from his father, asking for a meeting at California’s Culver City airport. They talked on the tarmac, in a huge Mercedes with black-tinted windows. Whether Raff knew that his son already had AIDS-like symptoms isn’t known but he offered to take him in.

Vivian declined.

By 1988 he returned to Australia, where he adopted his tribal name Kabul, meaning carpet snake, and with his mother, now known by her tribal name, Oodgeroo Noonuccal, co-wrote The Rainbow Serpent for Expo 88 in Brisbane.

Vivian died in 1991, aged just 38.

As for his mother and grandmother, the first lady of Indigenous poetry, Oodgeroo, and her former employer, Lady Cilento, both were nominated for Queenslander of the Year in 1981.

In time the Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital would be named for Lady Cilento in recognition of her contribution as a feminist pioneer, an advocate for the health of pregnant women and babies, and founder of Queensland Mothercraft (the name of the hospital was changed to the Queensland Children’s Hospital in 2018, after what seems to have been a political dispute).

In 2017, a new political district in Queensland was named for Oodgeroo.

“That to me is an interesting moment, where black and white Australia are coming together at the same level of respect,” Wilson says. “I think in some ways that’s the story I am telling: two strong women, two matriarchs. What did each of them know and think about the other?

“That is what the book is seeking to answer.”

This Accidental Present by Ross Wilson is published by AndAlso Books and will be available from May 25. The author will appear at Brisbane Writers Festival on May 11.

This is the story of two Australian families – one Indigenous, one white – bound by the birth of a child, in circumstances that demanded the utmost secrecy.