Once discredited, why ‘recovered memory’ is back before our courts

Dramatic shifts in who is prosecuted for sex offences raise the concern of lawyers including former prosecutor Margaret Cunneen, SC.

Three years ago, a South Australian father faced trial before a District Court judge after his 19-year-old daughter told police he had sexually assaulted her between the ages of seven and 10 while she was staying with him on access visits.

The young woman remembered her father climbing into her bed and sexually assaulting her on multiple occasions, incidents she never reported to her mother or a counsellor she had consulted in the years immediately after the abuse allegedly stopped.

Adelaide barrister Nick Vadasz remembers that case well because he was the accused father’s lawyer, and something unusual happened when the daughter was testifying in court.

During cross examination, she disclosed a detail that was not in her three police statements: she had “repressed” the memory of her father’s assaults until the age of 17, when she began remembering them while telling her psychologist about a separate incident that had happened at school.

“For years it was all blocked out of my mind, like all of it,” the young woman testified.

“All I remember is knowing that I really felt uncomfortable around Dad and I didn’t like the way he acted with his affection and stuff, and that continued on after the offending … I guess it was just blocked out of my mind for a bit until something else, which was the other thing with the other guy, kind of brought those feelings back up and I was, like, ‘Oh, I think there’s something else here’.”

Her testimony prompted Vadasz to consult an expert psychologist, Richard Balfour, who questioned the reliability of the young woman’s memories and testified that traumatic sexual assaults in childhood usually create intrusive and persistent memories, rather than being forgotten.

But the presiding judge was not persuaded, ruling that the daughter was an impressive witness; he found the father guilty and sentenced him to 12 years in prison, with a non-parole period of eight years. Nor did the Court of Appeal find any reason to question the judge’s verdict, declining to overturn it in a split decision. Last year, the High Court refused to grant the father leave to appeal.

Vadasz says that outcome is concerning in a case where the alleged victim had no memory of the crimes until she underwent counselling and then failed to tell police or prosecutors how her memory had been “triggered” by another event involving a different man. He agrees that sexual assault allegations were not taken as seriously as they should have been in the past but says the public mood has shifted towards believing an allegation must be the truth.

“The stigma attached to child sexual assault offences makes these cases very difficult to defend,” Vadasz says.

“The public attitude has shifted, quite correctly, but it appears to have resulted in an overwhelming view that assertion is the truth of the matter, and it’s very difficult to shift that view.”

The case is one of several recent prosecutions in Australia involving long-forgotten incidents of abuse. In 2021, a NSW schoolteacher was awarded costs after his trial for the alleged rape of a 10-year-old boy in 1995 was aborted; during the proceedings it emerged that his accuser had remembered the assaults only after undergoing a counselling technique called eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing in Thailand in 2016.

Last year, two separate defendants in Victoria were acquitted by County Court judges after their accusers acknowledged their memories of childhood sexual assaults had been repressed or “not consciously available” for years. One woman had recovered her memories after consulting Google about the cause of her pseudo-seizures; the other had been speaking to a psychotherapist about an unrelated assault in a car when she recovered memories of being sexually assaulted by a martial arts trainer 17 years earlier.

For the past eight weeks, The Australian’s Shadow of Doubt podcast has investigated the case of a jailed NSW couple whose daughter underwent psychiatric treatment and recovered memories of 13 years of sadistic sexual abuse in the family home. The treating psychiatrist testified that the young woman’s memories of her parents’ abuse had been “blocked out” until she suffered a sexual assault by a sports coach at age 17 and underwent counselling. The couple, who were sentenced to heavy jail terms, vehemently proclaim their innocence and are seeking a review of the case.

Sydney solicitor Greg Walsh, who is representing the mother pro bono, says the case is one of several he has seen in recent years that involve repressed memories of childhood abuse recovered in counselling. Professional counselling organisations have warned for decades that such memories can be false or unreliable, and Walsh says the re-emergence of these cases reflects a worrying trend.

He says evidence elicited through quasi-hypnotic therapy techniques such as EMDR is now being allowed into court, and defendants often are hamstrung by rules of evidence that restrict their access to an accuser’s counselling notes or the questions their lawyers can ask.

“Politically and also ideologically, politicians and so-called experts and others have been driving for an increase in the conviction rate,” he says. “They have a belief that accused persons are not being convicted as frequently as they should be, and there has been a concerted campaign to make it more and more difficult to defend yourself in these cases.

“And indeed, they’ve become so complex they’re beyond the means of most people who are accused, and they take up an enormous amount of time.”

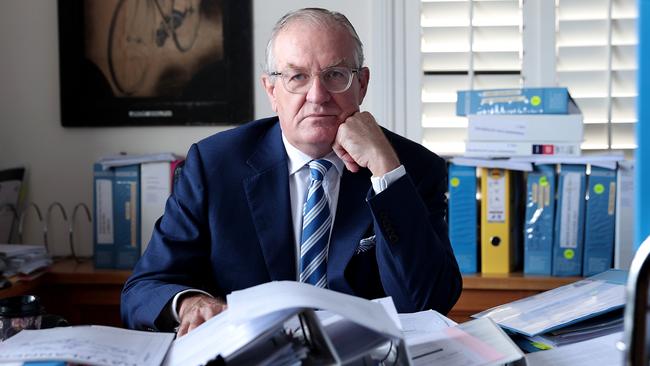

His concerns are echoed by other lawyers, including former prosecutor Margaret Cunneen SC, now a defence barrister, who says sexual assault matters make up 75 per cent of her caseload. As a prosecutor, Cunneen put many sexual offenders behind bars, including notorious gang rapists Bilal and Mohammed Skaf. But she says many of the defendants she is representing today would never have been prosecuted 10 years ago because the evidence against them would have been deemed inadequate or unreliable.

She says prosecutors in the current climate appear to see their role as supporting complainants rather than assessing cases on their viability. It’s an issue that has been central to the current inquiry into the rape allegations raised by former Liberal government staffer Brittany Higgins.

“The emphasis now is really entirely on the complainants’ side,” says Cunneen, “whereas the DPPs of earlier times used to foster the idea that we were the conduit between the police and the courts. We were told … that we represented the whole community, which includes the accused person, so we had to be vigilant to not put people through the dreadful disruption to their lives and their finances of a trial if there was no prospect of conviction in the end.”

Cunneen sees two dangers in the current trend. One is the possibility of innocent people being jailed because juries feel a public pressure to convict. Conversely, she believes many cases being pushed into the courts are destined to fail, with the ironic outcome that the conviction rate could drop. She says a preponderance of her clients have been charged over incidents in which a dating partner disputes whether consent was given, and that three-quarters of these cases result in acquittal.

“If you are not filtering anything out at the prosecution level and running everything, then you could only expect the conviction rate to decline,” she says.

Defence lawyers in child sexual assault matters see a different set of problems created by laws such as the relatively new offence of “maintaining a sexual relationship”, which removes the prosecution’s obligation to prove particular offences happened at certain times, instead lumping them into one all-encompassing charge.

Solicitor Andrew Bale says the effect of this is that jurors can now disagree on whether particular offences happened, but still find a defendant guilty of them.

“The jury (doesn’t) even have to be satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt that the same events occurred – each member of the jury can return a guilty verdict based on a different interpretation of a series of events, even if they disagree with other members of the jury about which events occurred.”

Bale was the original solicitor for the parents in the case detailed in the Shadow of Doubt podcast, in which the father was accused of inflicting 13 years of extreme violence on his daughter, for which there was no corroborative witnesses. He remembers that at one point a local prosecutor referred the case to the head office of the NSW ODPP for review because of its “problematic” nature, but the case still proceeded.

Bale himself lobbied prosecutors to drop the matter after securing evidence that the couple’s daughter had told a friend her allegations were based entirely on repressed memories that returned to her as an adult. Police responded by securing a statement from the daughter denying she had said any such thing.

Bale ended up withdrawing from the case after Legal Aid appointed new lawyers for cost reasons. The new legal team initially decided to fight the case on the basis that the daughter had experienced “false memories” of childhood abuse. They theorised that her memories might be linked to the presence in the family home of a known child abuser when she was young. That man, once a family friend, had groomed and abused her sister while living in the house for a year, something the parents had not discovered until nearly 10 years later.

But the lawyers faced a problem introducing this evidence – it would involve questioning the sisters about their prior sexual history. Such questions are generally not allowed in court, to shield witnesses from humiliating or offensive suggestions about their personal behaviour.

So the jury in the trial never heard this alternative theory about the source of the young woman’s memories. The lawyers ultimately did not fight the case on the repressed memory issue. They opted for the simpler approach of trying to convince the jury their clients’ daughter was lying.

The jury was not convinced, and the father was convicted on all 73 charges he faced and sentenced to 48 years in prison. The mother was convicted on 13 counts and is serving a 16-year sentence. It was a win for the ODPP, but today the case is still causing controversy – Walsh and Bale are hoping to secure a judicial review of the case, and a growing number of experts in the law and psychology see it as a problematic example of where the zeal to prosecute child abusers has led us.

“We’re in a political environment where it’s easier for a prosecutor to run the case and leave it up to the jury so as to avoid a potentially controversial decision,” says Bale. “I think cases like this highlight the problem with that.”

*The images used with this podcast investigation are for illustrative purposes only and bear no resemblance to the real people in this story, who cannot be identified for legal reasons.

–

Shadow of Doubt is available on The Australian’s app and shadowofdoubt.com.au

Subscribers hear episodes first and get access to all our bonus content including video, explainers and articles.