Last month, the council launched a multimillion advertising campaign on animated digital billboards, airport lounges and lifts in prime Sydney and Melbourne locations with the message that the discussion about nuclear power was risking Australia’s future. It is merely a foretaste of a much larger campaign as the Coalition prepares to seek a mandate for removing the nuclear moratorium at the next federal election.

Opposition climate change and energy spokesman Ted O’Brien has been at pains to frame any discussion about nuclear around its place in the energy mix. Intermittent, disbursed generation technology such as wind and solar would continue to contribute to the grid. Gas also would be a crucial part of the mix, principally because of its agility to ramp up or down, compensating for the vagaries of renewable energy sources.

Yet the renewables sector has bought none of it. It regards the election of a Coalition government as an existential threat that would devalue its portfolios overnight. Implicit and explicit subsidies would be phased out. It would hasten the realisation that there was a threshold beyond which the saturation of renewables in the grid became more of a nuisance than a help and that we might already be in that territory.

“It is becoming increasingly clear that the nuclear push is designed to bring the rollout of renewables to a halt – not just temporarily, but for good,” wrote Giles Parkinson, the editor of Renew Economy, the sector’s equivalent of the China Daily.

Giles says there are fears the nuclear push will create more uncertainty for a sector already battling with bottlenecks and roadblocks in planning decisions, network capacity, connection delays, social licence and market regulations that are struggling to keep up with the transition.

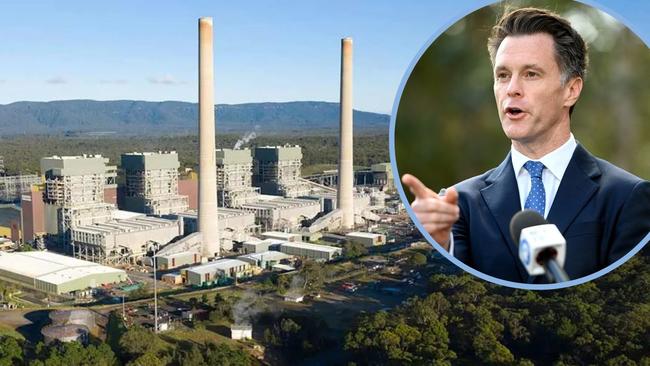

At the end of the week, the announcement that the NSW government would pay Origin up to $225m to keep the Eraring Power Station operating for two years beyond its planned 2025 retirement confirmed that renewable energy had failed to deliver on its promise to provide the capacity required to survive without coal. The Victorian government has been negotiating similar extensions with EnergyAustralia, the owner of Yallourn, and AGL, which operates Loy Yong A. Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen belatedly has recognised the need for more gas in the system. The theory that the grid can operate on renewables alone in the medium term is now unambiguously discredited.

The Australian Energy Market Operator presented a dismal picture of the pace of the transition in its forecast for energy supply in the next 10 years, named somewhat optimistically as the Statement of Opportunities. AEMO said it had been advised of “numerous delays to the development and commissioning of committed and anticipated wind and solar projects”, meaning the amount of energy in the system would be lower than predicted between 2025 and 2028.

This would increase the likelihood of unserved energy events, or blackouts as most people would call them. It gets worse. The new turbines and solar panels are rolling out at a fraction of the rate Bowen anticipated 18 months ago, and they need to get connected to the grid. Building 10,000km of new transmission lines has not been quite the walk in the park the minister seemed to have expected. Planning and construction delays and community resistance are putting transmission projects way behind schedule and over budget.

There is no good news for Bowen or the sector in the AEMO report. Project EnergyConnect, the interconnection between NSW and South Australia, was regarded as the most straightforward high-voltage transmission link since it passed through sparsely populated territory. Yet construction delays mean it will not operate at full capacity until July 2027 at the earliest. That will be too late to compensate for expected shortfalls once the Torrens Island B and Osborne power stations shut. In NSW, delays to battery projects mean supply will be even tighter than expected, and Victoria will feel the pinch from constraints on interstate transmission.

Even if we accept AEMO’s optimistic claim that there are plenty of projects in the pipeline, this is hardly the fast-track transition the government promised. In October 2022, Bowen told a gathering of business leaders that meeting the government’s 82 per cent clean electricity target by 2030 would require the installation of 22,000 solar panels a day, 62 million in total, by the end of the decade. It would require a 7-megawatt wind turbine to be commissioned every 18 hours, each as high as Crown’s One Barangaroo tower in Sydney. About 10,000km of new high-voltage transmission lines would be needed to link up the vastly expanded network.

Yet investment in renewable energy is happening at a snail’s pace. Only a handful of projects have reached financial completion since Labor came to power.

Which puts the renewables sector in a weak position as it launches its campaign to fight nuclear. It claims nuclear is a distraction and an expensive white elephant that won’t be needed once renewables are in place. Yet the renewables sector is reneging on its side of the deal to provide a viable alternative to nuclear energy. The government’s road map, devised by AEMO, abandons the centralised baseload principles on which the electricity grid has operated since its conception. Instead, it proposes a highly distributed system combining wind and solar with storage.

It is a novel concept based on untried assumptions. The only countries that have come close to living the renewables-only clean electricity dream are countries such as Norway that have an abundance of hydro-electricity and the ability to build onshore wind generators in and around the Arctic Circle where they can operate for more than 40 per cent of the time, compared with figures in the mid-20s for wind projects in much of Australia.

It means the heavy upfront investment in turbines, transformers, inverters and transmission produces close to double the return of similar investments in Australia once subsidies are discounted.

The consistent message from countries with grids already operating on carbon-free energy is that nuclear energy must be part of the mix. The accompanying map of Europe illustrates the point. The countries in green are those with electricity systems that have emitted less than 100 grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per kilowatt hour of electricity consumed across the past year. Every one of them, except Iceland and Norway, uses nuclear power. Norway is powered almost entirely by hydro, with less than 3 per cent of the energy generated by biomass and wind. Iceland has the rare gift of accessible geothermal energy, contributing 28 per cent of the total mix. The rest came from hydro.

EU data shows retail electricity prices were consistently lower than the European average in these countries. For example, consumers in Sweden, Finland and Norway paid about half the cost of those in Germany, which abandoned nuclear power and invested heavily in wind and solar energy.

To counter this real-world evidence, the renewables sector leans heavily on the CSIRO’s controversial calculations in its GenCost report, which claims renewable energy is far cheaper than nuclear. GenCost’s chief limitation is that it compares the levelised cost of electricity at an individual project level, which inadequately accounts for system costs, including the costs of transmission and back-up.

This week, the CSIRO estimated that a large-scale nuclear power plant would cost at least $8.5bn to build in Australia. That figure seems credible based on the experience of Finland, where the Olkiluoto 3 reactor went online a year ago for $9.7bn.

The relevant question is not the size of the investment but whether it represents value for money and whether the owners (a private Finnish consortium) can expect a commensurate return across the life of the project.

The answer to both questions is unambiguously positive. Olkiluoto 3 can operate for 95 per cent of the time at a steady output of up to 1.6 gigawatts. It has a conservative lifetime of 60 years, but the owner is confident its life can be extended for at least 20 years beyond that and that there is a reasonable chance it will be operating at the turn of the century.

As a third-generation pressurised water reactor, it represents the first of its kind. The engineers overcame many challenges along the way, including the storage of nuclear waste, which will be packed in sealed copper capsules and buried 430m below the ground in stable rock 1.9 billion years old. Once complete, the containment tunnels will be filled with bentonite, the main ingredient in cat litter, and sealed with giant concrete plugs.

Having visited the site last week, I can confirm the tunnels are in place, testing is nearing completion, an elevator is installed and burial of waste is likely to begin in the European autumn.

Increasingly, the policy question is not whether Australia can clean the grid without it. For all its talk, the renewables sector is taking us nowhere fast.

How long can we afford to stick with a plan with uncertain potential that relies on numerous forms of new technology untested at scale? If the renewable energy sector is confident these things will work and can be delivered on budget and time, it will not fear nuclear as a competitor.

Yet the industry is well aware that the renewables-only path is precarious. The capital markets tell them so: private investors are unwilling to risk their money in renewable energy projects without compensation from the government. The Capacity Investment Scheme, in which the government guarantees a loan return, is a risk-shifting exercise, transferring uncertainty that the capital markets find intolerable to the taxpayers.

Real-time data from AEMO offers a sobering reality check. In the 24 hours that ended at 3.30pm on Thursday, the east coast grid (national electricity market) was running on 76 per cent fossil fuel and 24 per cent renewable energy, including 8 per cent hydro. If this represents an improvement on the mix when Labor came to power, it is too small to be visible to the naked eye.

The Clean Energy Council describes itself as the peak body for the clean energy sector. It is not. It is a powerful, cashed-up lobby group promoting the interests of wind, water and hydro generators with a mission to kill nuclear energy stone dead in Australia.