NSW floods: lives and livelihoods swept away in a too-familiar story

For more than 200 years, dwellings near NSW’s Hawkesbury River have been ravaged by floods.

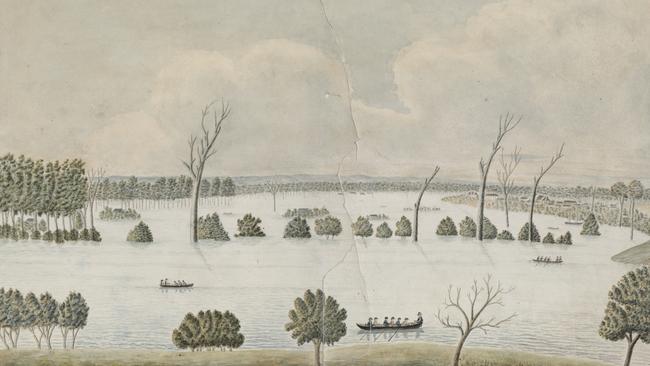

Wheatstacks floated with “incredible velocity” down the flooded Hawkesbury River, some carrying “pigs, dogs and prodigious quantities of poultry”. Walter Scott, a shoemaker, was swept to his death, leaving a large family to “deplore his destiny”. The night echoed with the wailing of dogs trapped in trees.

A few years earlier, the fledgling colony of NSW had been gripped by drought. The wheat harvest had fallen by two-thirds, pasture was exhausted and streams were dry. Now, in March 1806, the colony’s most important food-growing district “had no other appearance than that of an immense sheet of water”.

The first intimation of disaster came on Thursday March 20, 1806, when the Hawkesbury, “discoloured”, rose several feet above the high-water mark. Overnight the floodwaters seemed to abate, but rain continued to fall on Friday and all through the following night. As dawn broke on Saturday, “a scene of horror” — in the words of the Sydney Gazette — “presented itself in every quarter”.

The chief constable, Andrew Thompson, a Scottish weaver’s son transported for 14 years for stealing £10 worth of cloth, braved the floodwaters in his rowboat, pulling scores of terrified settlers from rooftops and from “rafts of straw” floating on the deluge.

Citizens and district constables risked their lives to help stranded settlers. One, Thomas Biggers, was credited with having saved “upwards of 150 men, women, and children”.

All Saturday it poured. By nightfall only the roofs of a couple of the tallest houses could be seen above the water.

William Leeson, his mother, wife and two children were carried away from his farm “upon a barley mow” and driven nearly seven miles by the “impetuous” current.

Two lime burners working near the coast reported seeing 20 wheatstacks heading out to sea.

Terrified settlers trapped on rooftops or in the branches of trees fired their muskets in the darkness to attract attention.

“Dismal cries from distant quarters, the report of firearms dangerously charged in order to increase the noise of explosion; the howling of dogs that had by swimming got into trees, all concurred to shock the feelings of the few that were out of the reach, but were sorrowful spectators of the calamity they could not relieve.”

The Gazette reported that five people had drowned. The livestock toll was 3560 pigs, 16 horses, 47 sheep and 296 goats worth a total of £7454.

The value of crops destroyed by the flood was three times that.

In the aftermath, profiteering was rife. Bread, which could be bought for fourpence a loaf before the flood, was soon changing hands for two or even five shillings a loaf.

The government reduced weekly rations and imposed limits on the sale of bread to “private persons”.

The prospect of food shortages increased when two ships sank on their way to fetch rice from India and China. Governor Philip King made plans to send a “small, fast vessel” to Madras for rice on what he hoped would be a quick return trip of four months. At the same time, he wrote to his colonial bosses in England, pleading for hundreds of bushels of wheat to be sent in time for the following year’s planting season.

Before relief could arrive, King was gone, worn out by his struggle with the rum traders, led by John Macarthur. The 1806 Hawkesbury River flood was a “calamity that threatens the very existence of the colony”, Macarthur wrote to his friend Captain Piper at Norfolk Island. “What a scene for a new governor and what a fine subject for a panegyric on the care, wisdom and foresight of our friend (governor King).”

King’s replacement, William Bligh of the Bounty, arrived at the start of August to find the unfortunate settlers “almost ruined and starved”.

Although he endeared himself to the Hawkesbury settlers by organising relief supplies and boosting meat rations, the foul-mouthed Bligh made too many enemies in Sydney and was soon heading back to London, another victim of Macarthur’s machinations. A schemer and scoundrel, Macarthur was not the last Australian to try to score political points out of a natural disaster, but this time he was right.

Since the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788, the Hawkesbury region had been noted both for its fertility and for its propensity to flood. While exploring with governor Arthur Phillip in 1789, Captain John Hunter had noticed debris lodged in trees 10m to 12m above the level of the river.

The garrulous diarist Watkin Tench spotted flood litter nearly 14m above the normal height of the Nepean River.

But ambitious settlers arriving at the Hawkesbury saw only fertile land. On a surveying expedition in December 1791, Tench reported visiting “the farm of Christopher Magee, a convict settler, nearly opposite to that of Mr Scheffen; the situation of this farm is very eligible, provided the river in floods does not inundate it”.

Twenty-six settlers granted land on the Hawkesbury in 1794 “seemed very much pleased with their farms”, wrote lieutenant governor Francis Grose, as everything they planted had “grown in the greatest luxuriance”.

Bligh’s successor, Lachlan Macquarie, made a stab at flood mitigation, proclaiming five new towns — Richmond, Windsor, Wilberforce, Pitt Town and Castlereagh — on high ground along the Hawkesbury and Nepean Rivers in the hope of luring settlers away from the flood-prone river flats. Yet a decade after the 1806 floods, Macquarie complained to Lord Bathurst in London that it was “impossible not to feel extremely displeased and indignant at (settlers’) infatuated obstinacy in persisting to continue to reside with their families, flocks, herds, and grain on those spots subject to the floods, and from whence they have often had their prosperity swept away”.

In 1806, the Sydney Gazette bemoaned the “false notion of security which many had imbibed, from the supposed confidence that there never would be another heavy flood in the main river, though without assigning any cause for such an idea”.

Between droughts there would be more floods: in 1809, 1811, 1817, 1857, 1860, 1864 and, worst of all, in 1867, when the Hawkesbury rose by a record 19m at Windsor, drowning “1000 valuable horses” and smothering the district’s rich alluvial soil with “a thick layer of white sand” as much as 5m deep.

THOUSANDS RENDERED HOMELESS, screamed a headline in the Illustrated Sydney News on July 16, 1867. LOSS OF LIFE AND PROPERTY. HUNDREDS OF HOUSES SWEPT AWAY.

By then, it was a sad but all-too familiar story.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout