Nothing black and white about William Tyrrell case

There’s always something the police won’t divulge in a homicide case. In William’s, it was a detail on his suit that only very few knew.

There is always something that police aren’t saying. That is true not only for the William Tyrrell investigation, that is true for every homicide. Police tend to keep at least one key piece of information, something only the killer would know, away from the public. In the case of missing foster child William Tyrrell, it had to do with the suit he was wearing.

How many times have you seen the photograph of William, roaring like a tiger on the deck of his foster nana’s house in the bush village of Kendall on the NSW mid-north coast? How many times have you heard that he was dressed, when he went missing, in a Spider-Man suit? The photograph shows him in the suit — red and blue, with black stripes. The spider on the back, though, that was not black. It was bright white. Until this week, hardly anyone knew that.

William’s foster parents knew. Gary Jubelin, who for four years was the lead detective on the case — he knew. The person who took William? He, or she, or they probably knew too.

And why is that important? Because a debate about that white spider — who saw it and when — has been revealed this week as one of the factors that tore apart the investigation into William’s disappearance. It led, in a roundabout way, to the end of Jubelin’s career. It goes some way towards explaining why Jubelin was recording conversations with a “person of interest” in the case without the proper warrants. When the top brass found out, Jubelin was charged under the Surveillance Devices Act, and he has been on trial in Sydney for two weeks.

The trial has exposed the inner workings of the homicide squad: the staff shortage, the bitter rivalries, the robust language, the equipment failures, the lack of planning, the mental breakdowns.

Some senior detectives have been accused of not caring a hoot for William, who was three when he went missing. Others such as Jubelin have been accused of real acts of desperation as they tried to crack the case.

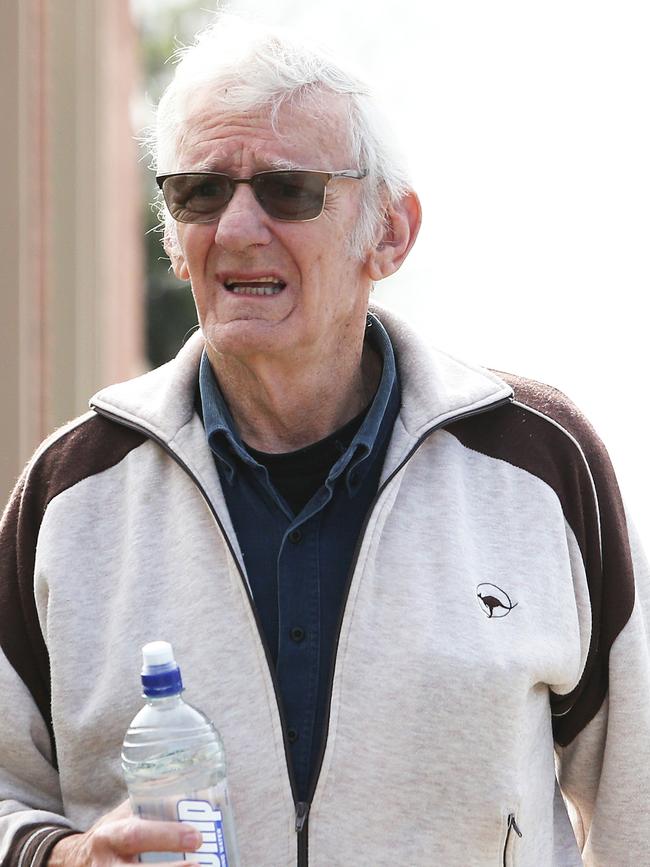

And so, to go back: Jubelin decided in 2017 to target for surveillance an elderly neighbour, Paul Savage, who was 70 when William went missing. There is no evidence linking Savage to the crime, but Jubelin told the court he was “suspicious” of him.

Savage lived in the house across the road from William’s foster nana, in whose garden William was playing when he went missing. He was at home that morning. He was, in Jubelin’s words, “the street stickybeak” who always knew what was going on around Benaroon Drive, yet he claimed not to have heard the commotion in the street when William went missing, around 10.30am.

Savage previously has said he had Ray Hadley on the radio, very loud, when he heard a knock on the door. It was Anne-Maree Sharpley, who lived a few doors up, telling him about William.

Savage says he stepped straight out and joined the search. He went up into the bush behind his house and “got a bit lost”. He came home after more than an hour and had a cup of tea.

Jubelin thought that was strange. How could Savage have got lost? He walks those bush trails every day. He had lived in the area for decades. He knew those tracks like the back of his hand.

Also, why would he go inside when he finally found his way down, and have a cup of tea, and not join the neighbours in the street, at least to say: I’ve been up in the bush, I didn’t find him?

He began looking into Savage’s personal life. He had been married to wife Heather for more than four decades but, in the year before William’s disappearance, and according to evidence given in court this week, he seemed to have developed an “obsession” with the local “post lady”.

“He would tell her that he loved her,” Jubelin said. “He would go up to the post office, shaking and crying, and saying they had to be together.”

She said she had never done more than exchange pleasantries with him when delivering mail. When Savage followed her in his car one day, she took out an apprehended violence order, and he breached it by stopping one day to wish her a happy birthday. Savage went to court and pleaded guilty. He backed off the post lady but when Jubelin asked around, he discovered that Savage had also been asked to stay away from William’s foster nana.

She had become widowed in 2014 and was living alone. According to evidence presented to the court, Savage had started to turn up at her back door. He was only looking out for her, he said. But she told Heather that her husband was making her uncomfortable. Savage promised to stay away.

On the day William disappeared, Heather was due to go to bingo. The post lady was due to deliver mail. William was running around the garden of his foster nana’s house. He was unattended for just a few moments — and then he was gone.

Jubelin wondered: had Heather pulled out, to go to bingo, and run William over? Had Savage gone out to see if he could see the post lady, and come upon William instead? Had William wandered into Savage’s yard? Had he accidentally drowned in an old pool on Savage’s property? Again, there is no evidence, but it all got Jubelin thinking. Another thing troubled him. About six months after William went missing, Heather died, and Savage had taken to walking around the village with an A4 picture of his dead wife around his neck. “That’s unusual behaviour,” Jubelin told the court.

He decided to target Savage for surveillance. He had bugs placed in his house and car, and on his mobile phone and landline.

Savage lives alone, but he mutters to himself pretty much constantly. It was hard for the police to keep up with the chat.

Jubelin prides himself on creative policing. He came up with a plan to bury a Spider-Man suit in the dirt, to make it look old, and then to place it on one of the bush trails known to be frequented by Savage. He had undercover officers hide in the bush to record what might happen when Savage came upon the suit. Would he pick it up and run with it, straight to the police? Would he try to hide it?

The trap was laid. The suit was placed on the track on July 26, 2017. Savage came walking by and then, 5½ steps past the suit, he suddenly stopped. He appeared to bend at the waist and look back. Then he kept going. He did not report the suit. He insists he did not see it. Police tried again the next day. This time, Savage definitely saw the suit, hurried straight back down the trail, and reported it to police, and here is where the problems started. Jubelin was not there to see Savage stop, or not stop, by the suit. He had to rely on a report by the surveillance officer in the bush, who said that Savage had stopped just past the suit on July 26, and that he looked back at it, for around 12 seconds.

Not everyone agrees that is what the tape shows. Some of the other detectives on the strike force thought it just wasn’t clear from the tape whether Savage had stopped to look at the suit.

On October 5, 2017, Jubelin told Savage it was police who left the suit on the walking trail. He took the photographs of Savage in the bush near the suit. He told him that he knew he’d seen the suit a day earlier, but hadn’t reported it. Savage denied it.

Jubelin left him alone to think about things. Then, in a series of conversations picked up by the listening devices in his house, Savage said, either to his daughter or to himself: “Because it wasn’t the suit … it wasn’t the suit Gary, it was half the suit. I’m not sure, I think it was the top half of the suit … from memory, the white bit, the white top or whatever it is, with the spider. That’s why I, that’s why I stopped. I was looking around.”

A day later, on October 6, 2017, Savage called Jubelin at home. This time, he said: “When I walked up there, I seen the white top, I think it was the white top with the stripes, and it was covered in dirt.”

Jubelin says he was stunned. William had gone missing in a Spider-Man suit with a white spider on the back, but the suit that police had laid on the track? No white spider. It had only a black spider.

Jubelin told the court he now thought Savage may have been “describing the suit William had disappeared in, and not the suit we had laid on the track”. This was a potential breakthrough. But again, there was disagreement.

What is Savage actually saying on those tapes? Is he saying he didn’t see William’s suit but somebody else’s white top? Or is he saying he only saw the top half of William’s two-piece suit, “the white bit, the white top or whatever it is, with the spider”?

Jubelin had, shall we say, fewer doubts. He began to apply intense pressure. A series of robust conversations took place, and Jubelin made sure to capture four on them on his mobile phone.

He didn’t have a warrant to do that. He has told the court he did so to protect himself. The police equipment often failed, and he didn’t want Savage to accuse him of threatening him.

The conversations don’t make for easy listening. Jubelin tells Savage that he thinks he had something to do with William’s disappearance; that he’s covering up, maybe even for Heather; that his behaviour has been erratic and strange; that his unrequited love and emotional betrayal of Heather are about to become public; that he should just tell him what happened, so everyone can find peace.

He did not get a confession.

Savage has always denied wrongdoing. There is no evidence linking him to the crime. Indeed, there is no evidence linking anyone to this crime.

Five years after William’s disappearance, the only person ever to face court is Jubelin, for recording those conversations. It will be for the magistrate to decide whether he’s guilty of a criminal offence. Those members of the public who turn up to cheer Jubelin on his way up the steps every morning would seem to have made up their minds.